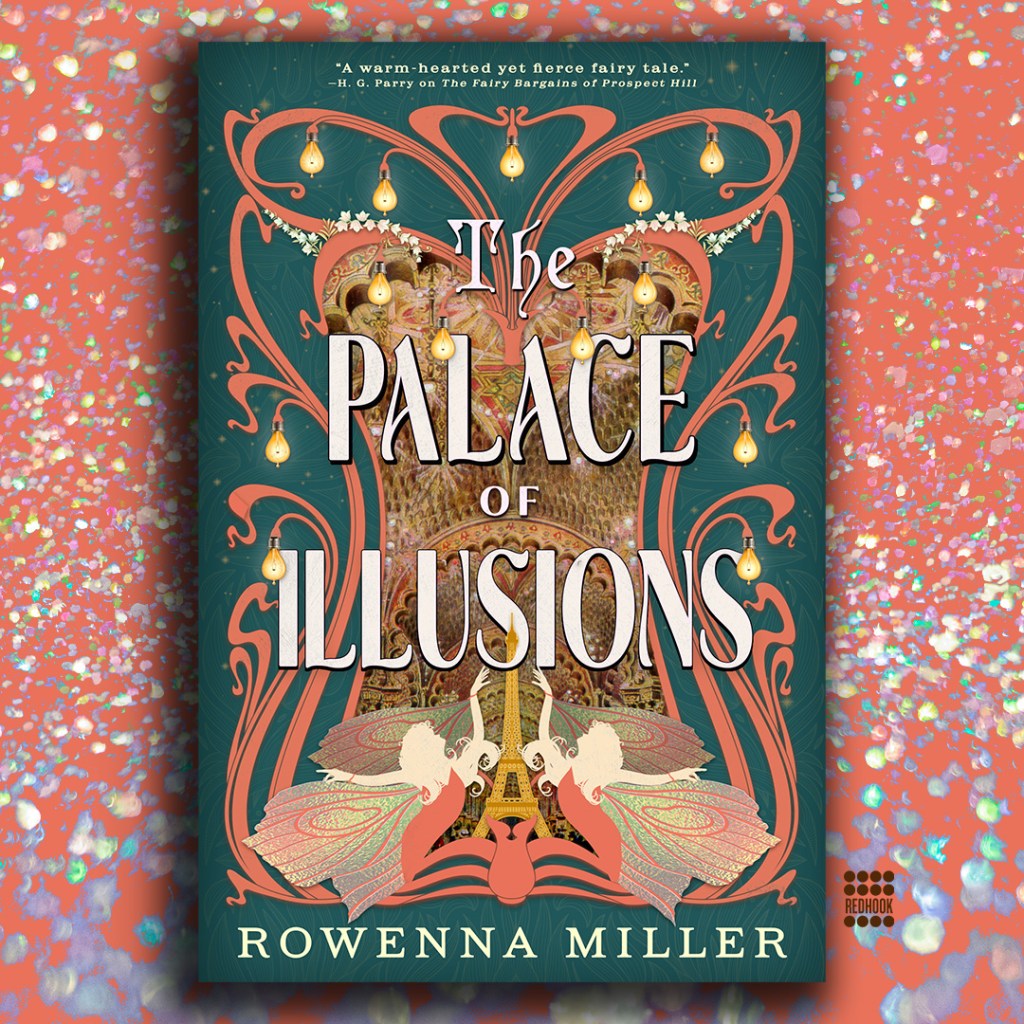

Excerpt: THE PALACE OF ILLUSIONS by Rowenna Miller

The Palace of Illusions brings readers to a Paris breathless with excitement at the dawn of the twentieth century, where for a select few there is a second, secret Paris where the magic of the City of Light is very real in this enchanting and atmospheric fantasy from the author of The Fairy Bargains of Prospect Hill.

Read an excerpt from The Palace of Illusions (US), on sale June 10, below!

Chapter Six

Clara hurried home through nearly barren streets. A light snow fell and settled on the tops of streetlamps and in the crevices of gutters. Flakes caught in the lamplight, suspended for a moment as though caught in time, and Clara was surprised to feel a sharp point of cold where a tear slipped down her cheek.

She hadn’t expected to miss home. It was silly, she chided herself, letting some children and the scent of gingerbread send her into homesick nostalgia. But Christmas had always been a happy time in the Ironwood house. No, it was more, she admitted as she allowed another tear to turn into a tiny icicle as it went its way down her face. When she thought of Christmas at home, she thought of before—before she had ruined things with Godfather.

In her gilded memories of childhood Christmases, Godfather was always there, mischievous, hovering on the periphery or inserting himself into the center of activity. And always with his gifts. Strange clockwork scenes and toys that jumped, flew, and even danced as if by magic. When she was eight, Godfather gave her and Louise two-foot-tall dolls in harlequin patchwork that, when properly wound, sprang over a yard into the air, arms and legs flailing comically. When she was ten, Godfather brought a pond of shimmering stained glass set with ornate metal swans. They swam on the surface of their pond, weaving to and fro and around one another in a complicated minuet.

She knew now how he made the toys—the patchwork dancers were loaded with springs, and the swans only danced because of magnets under the glass. But there remained a nostalgic enchantment to them. They had been magic to her, once. She wanted to create that feeling herself, and so she had apprenticed under Godfather and that—that had destroyed the last of the magic she might have harbored from childhood.

The apartments surrounding hers were lively, unsurprising as friends gathered and families celebrated. Foolish of her, to think she could capture some glimmer of those Christmases at home here, far away, among people she barely knew. At least her closest neighbors were quiet. Probably, Clara wagered, away for the evening, sharing bottles of wine and fruitcakes, or wedges of cheese—or whatever Parisians ate for Christmas Eve. She unlocked her silent apartment and sat with a heavy thump on the settee.

Godfather’s nutcracker teetered on the shelf above her and fell. She lunged and caught it as it hurtled to the floor. She wondered if saving that hideous face was really worth the requisite athleticism as she propped the nutcracker on the settee beside her.

“Well, it’s just you and me tonight. Do you have a name? I shouldn’t wonder if you did—Godfather tended to name things. What was his clock’s name—Hugo Hourly.” The nutcracker stared back at her with unseeing though baleful eyes. “Don’t blame me, I didn’t make up that horrible pun.”

She picked the nutcracker up again, opening the secret compartment under the cap. Inside, the delicate glass glinted at her as though asking her to pick it up. It was a pretty little thing, if nothing out of the ordinary, really. Just a magnifying glass.

She held the glass up, looking through it for the first time. The framed prints on the wall wavered and buckled through the lens, and the lamplight distorted and grew wan at the edges. Then the light seemed to press into the center of the lens, brightening to a warm white that pulsed gently.

She pulled the glass way, expecting to see the lamp blazing or even a small fire overtaking a corner of the apartment. The same dim light greeted her, cheerful enough but hardly brilliant. Tentatively, she looked through the magnifying glass once more. It must be bending the light in some unexpected way, she guessed, reminding herself not to hurt her eyes looking at an artificially intensified light. With deliberate care, she tilted the lens away from the lights, looking instead into the dark corner of the apartment where a largely neglected potted plant lived. It drooped, blurry, in the glass.

The light ebbed and lapped at the edges of the lens again, even though there was no lamp nearby. As it did, the plant seemed to change. Though it was difficult to see clearly, the flat leaves seemed to curve upward and brighten, faded green burning bright emerald as the stalks twined and grew. She squinted, wondering what properties of the glass could create such illusions.

The light unfurled toward the center of the glass again, softly warming like the horizon before the sunrise—a dramatic change from darkness, but not painful to look at. It drew tight toward the middle of the glass, an eye closing swiftly, and as the light coalesced it suddenly flared so strongly that Clara clamped her eyes shut.

When she opened them, the world had turned inside out.

Her dim apartment was awash with light from a brilliant sunrise—or perhaps it was a sunset, she couldn’t tell—outside the window. It had been the depth of night just moments before, she was sure—had she fainted? That would explain the light, but it wouldn’t explain the changes in her simple, spare apartment.

Clara was quite sure that the walls had never before been covered in pale blue silk, and the mirrors and picture frames had been in chipped dark wood, not gilt. The plant had grown into a topiary of a strange bird, graceful curves rendered in brilliant green leaves. The simple clock hanging on the wall had transformed into an intricate grandfather clock not terribly unlike Godfather’s, but in paler wood and, she saw, featuring songbirds and vining flowers on its golden face instead of the stern owls and constellations Thrushman favored.

She blinked, not believing her own eyes.

She ran to the window and opened it, letting the pale pink light flood inside. It was not only faintly rosy in hue, it smelled of flowers—of rosewater and the tea roses in a summer garden. The harder Clara tried to catch the scent, the more it retreated, but when she paused, it rushed over her in a wave of sweet perfume and nostalgia. Outside, a light snow fell, swirling over a city she recognized only distantly.

She turned her attention back inside, letting herself adjust to the inversion of her own apartment. It was completely different and yet not strange. If she had imagined an apartment into being, she would have thought of something very much like this place—the colors, the delicately rendered details. She opened the door to her bedroom to confirm that her dented brass bedframe had been replaced by a sweeping four-poster with fluttering pale curtains. She was quite sure that her ceiling had been too low for it, before.

With shaking hands, she pulled her coat back on and opened the door of the apartment, tucking her key into a pocket, vaguely aware of how absurd it was to think about locking up when she had, apparently, broken reality. The stairs were no longer heavy dark wood, but a filigree spiral suffused with the rosy sunrise light. She clutched the glass in her hand, not daring to let it go.

She hesitated as she reached the street—was this safe? Probably not, she ventured. But it was impossible to resist. She had to know more, to understand, and to do so, she needed to see. Experience was, she had always felt, the best teacher. She didn’t understand the mechanisms of a clock until she put her hands to the gears, and she knew without articulating as much that she could not understand the strange beauty she beheld until she moved among it.

The route Clara usually took toward the Seine was still familiar even though it looked entirely different, as though someone had stripped the wallpaper from the world and redecorated, the bones of the structure left intact but everything else completely altered. The soft fall of the land, the way it dipped slightly as she approached the river; a grand white dome rising on the hill in the distance where the incomplete Basilica of the Sacré-Coeur held court in the world she knew.

She passed buildings she had seen every day, now layered in absurd and confusing complexity. Some apartments yielded nothing but the same blank, dark windows; others blazed with multicolored light. Some building facades remained plain while others had turned into Gothic cathedrals in miniature or were overgrown with flowering vines. Some individual apartments’ exteriors took on the look of baroque palaces or gingerbread cottages. At turns, however, some apartments sank into a clouded darkness. One building, which she knew as a counting-house, was a thick smudge of near nothingness.

The courtyards were the most mesmerizing. Each held storybooks in their four walls—evergreen forests with mushrooms as tall as a child, tiny but trim brown-and-white villages in orderly streets, or medieval castles with high towers. One was guarded by what Clara was sure was a dragon; on second look, it turned out to be a boxwood topiary of enormous size.

The sunrise light was laced with gold by the time she reached the river. She gasped—the Seine’s brackish brown was now pale pink, as though the river had absorbed the color of the sky and held it. Fragrance bloomed from its waves, too, a stronger and more concentrated perfume than she had caught before, but in the same fresh rose. Clara wondered if the scent had come from the river or from the sunrise itself, and decided, as the current began to take on a pale golden hue, that perhaps it wasn’t a simple answer.

As she watched the colors shift and change, she noticed a sound that seemed to emanate from the river. She walked closer, discovering as she did that the bridge she had taken every day had transformed from its pale stone to a web of spun glass suspended between spires of crystal. Fascinated, Clara examined it, the river’s sounds momentarily forgotten. The bridge’s nearest pillar was solid under her hands, but she had no idea how such a structure could have been created. The spires were intricately spun, as though a giant glassblower had wound them from the spool and planted them, still hot, in the riverbank.

She couldn’t be sure if the color she saw in the glass was a reflection of the sky, the river, or both. As she brushed the glass, the pink hues intensified under her fingers. Startled, she yanked her hands back, and the color ebbed and crept under the surface of the glass, bleeding several feet in every direction.

Unnerved but even more curious than before, Clara turned back to the river. The sound was not quite birdsong, not quite the gentle rush of the water. It was musical, and intentionally so, Clara realized, recognizing the interplay of harmony and melody, deliberate crescendo and precise ritardando.

The waves were singing.

Clara stopped, jaw slightly unhinged, and stared. Of all she had seen, this caught her, shook her, insisted that the world she was moving through was not anything she had seen before, was nothing she understood. The waves were singing, and though the sound was not quite human, it belied an intelligent musicality. She edged away from the bank of the river, wondering what other secrets it might hide.

For the first time, it struck Clara that not only might this place not be entirely safe, but there might be something human—or not quite human—watching her, marking her movements. Was she alone? She couldn’t see anyone else, but someone had made the wonders lining the streets and bordering the Seine. The thought was unnerving.

And then she realized she had no idea how to get back.

Chapter Seven

Clara stood on the banks of the transformed Seine, listening to the symphony of the water, and trying to decide what to do next. On the one hand, she couldn’t shake the chill of realization—she was either trapped in some sort of alternate Paris or she had gone quite mad. It didn’t feel like a dream, not at all—Clara’s dreams were perfunctory recitations of memories and anxieties and never had the scents, music, and saturation of color of this place.

She had heard of people having terribly realistic illusions after drinking absinthe, but she had never touched the stuff, or anything else that might result in imagining herself in a fantasy of her own making. She hadn’t had anything to drink besides the glühwein, and she didn’t see how that could result in hallucinations. And when people went mad, she reasoned, they usually did so a little at a time, not all at once like Alice falling down the rabbit hole.

So this place had to be real. She stood stock-still for a long time, unable to quite fathom the only logical conclusion she could draw.

Real. The singing waves, the perfumed sky, the glassworks bridge that changed color when she touched it. Real.

Though caution nagged at the edges of her mind, the underlying fear that, unlike Alice, she wouldn’t be able to get back home again, she yielded to wonder.

What else might she find? She made up her mind to cross the bridge.

The rose scent intensified and shifted over the water, brightening and unfurling until it was a garden of floral notes. The music, too, was louder here, but never coalesced into a melody Clara could follow. She paused in the middle of the bridge to look up and down the Seine, but the rose color hovered in a vapor like early morning mist, and only the faintest shapes could be seen struggling to take form. She thought she saw a grand structure where the Eiffel Tower ought to be, but couldn’t be sure, and the shape seemed not quite right. She turned back to the far bank.

There was a sunrise on the other side of the bridge.

At least, that was what it looked like. The soft, shifting hues and undulating light were, Clara discovered as she approached, flowers and pale mist, a garden unfolding even as she watched. As the blooms opened, slowly and almost imperceptibly, the colors changed from the murky purples of predawn to gilded rose to brilliant saffrons and corals. Just as they had erupted in full color, they faded again. The entire garden rippled in variegated color. Clara moved through it in awe, appreciating slowly that the scent of the flowers matched the intensity of the light, musk brightening to citrus.

She emerged onto what should have been a street but was paved in what appeared to be tightly overlapped shells that shimmered opalescent in the light of the sunrise garden. She stepped tentatively, expecting to feel them crush under her boot, but her heel made a crisp rat-a-tat on the strange pavement. The Jardin des Tuileries was—should have been—ahead. Curious what its mirror might be here, she navigated toward it past buildings that must have been made of sandalwood, given the scent emanating from them.

The Jardin was where she expected it to be. Tall hedges still hemmed in the gardens, and fountains still burst to life within the green walls, but instead of the carefully trimmed ornamental shrubbery and wide avenues, the space was crowded with trees. Christmas trees, Clara realized, gently shaped of fir and spruce and even boxwood, but trimmed with candied fruits that shimmered with sugar. Gently flickering lights, warm and alive like candles but without the tapers or wicks, illuminated the depths of the boughs. Though she couldn’t place it, the faint aroma of gingerbread hung in the air.

“Bon matin!”

A bright voice, too melodic to be quite human, pierced the quiet and nearly frightened Clara out of her skin.

“Bon matin! Et c’est vraiment un bon matin!”

She turned slowly, locating the source of the sound.

A tall woman, dressed as a shepherdess. No, Clara amended, the imagined ideal of what a shepherdess might wear, the sort of clothing suited to a porcelain figurine or a ballet costume, with full skirt and useless apron and a tightly cinched Swiss waist. The woman, too, was an oddly perfect ideal, with pale, smooth skin and abruptly rosy cheeks and lips. A pert tricorn hat offset perfectly coiled curls of dark hair. Her hands were poised like a dancer’s, her stance an alert first position.

“Good morning,” Clara managed to choke out.

“Oh! English! I am able to speak English.” The strange shepherdess smiled brightly. “I am versed in French, English, and German. Is English your preference?”

“Yes?”

“Then good morning!” She dipped a curtsy that looked more like a stage bow. “Have you come for the ballet?”

“I’m sorry, I didn’t—ballet? In a garden?”

“Oh, then I suppose you haven’t. It’s been a very long time since we had an audience. It has made some of us rather rusty, I’m afraid. Would you, do you think? Would you like to attend the ballet?”

“I—all right?” At Clara’s timid acquiescence, the shepherdess took action. She produced a gilded chair with a velvet cushion from behind a stout spruce decked in sugared grapes. Then she clapped her hands, and a pair of huntsmen appeared, one with a violin and the other with an oboe. They did not greet her or even seem to acknowledge Clara’s presence, but took their places in a small clearing.

The boy with the oboe began to play, and the violin chimed in, producing a gentle waltz that Clara thought she might recognize. The ballet began. The shepherdess who had spoken with her took the mossy stage as a soloist, each step and pirouette mesmerizing. When she leapt, she seemed to float, momentarily weightless and suspended only by the melody. Clara was not trained in the techniques of ballet, but the movements were all precise and crisply executed, in perfect unison with the music. Even Clara was fairly sure that the technical complexity of some of the combinations was of an exceptionally difficult level.

Then, suddenly, in the middle of a musical phrase, the violinist stopped, followed by the oboe player, and they wandered away into the forest, leaving only the shepherdess standing in the clearing.

She sighed. “And there you have it. Quite imperfect, unfinished really.” She curtsied again. “But I thank you for your kind attention.”

“It was magnificent!” Clara stood, applauding belatedly. “Why, you could have your choice of ballet companies!”

The woman laughed. “Oh, no! Quite impossible. We cannot leave, of course.”

Clara paused, the trickle of fear returning. “Does that mean that everyone who… who finds themselves here is trapped?”

“Trapped! No, of course not. The craftsmen come and go as they please, of course. They’re not like us, and neither are you, I presume—you are a craftsman, too? Craftswoman? Drat English, it hasn’t got proper gendered nouns, you know.”

“I’m a clockmaker,” Clara ventured.

“Yes! A clockmaker! Our own craftsman was a clockmaker, a very good one. It has been many years since he visited us, you see, and left the choreography quite unfinished. A pity, isn’t it? The ballet is so good up until the end and then—well. You saw.” She paused. “Would you like to see it again?”

“Oh, no, not—not right now.” Clara watched the woman as she picked at her skirt, the folds falling perfectly under her deft white fingers. “What is your name?”

“I am called Olympia.” She smiled. “And you? You have a name, too, I would imagine?”

“Clara Ironwood.” Clara searched the woman’s pale expression. “I’m sorry, but this is all still very strange to me and—how is it that a ballet dancer lives in…” Should she call it Tuileries? “Lives in the woods?”

“This is where we were put, my musicians and I.” Olympia shrugged.

“That’s not quite what I meant.”

“No, I suppose it isn’t.” The woman’s face took on a thoughtful pout. “We are here because we were fashioned to be here. As you are fashioned to be, for the most part, elsewhere.”

Slowly, Clara began to realize she hadn’t understood at all. “Fashioned?”

“Of course. Made, created, crafted, produced. I don’t know how you consider it—but a craftsman made us to live here in the wood. His mechanical ballet.”

Clara stood for a long moment in stunned silence. “You’re clockwork?”

“Yes.” Olympia folded her hands with intentional politeness. “Now, I don’t mean to chide, but it’s a bit rude to balk at it. I don’t make a fuss over your being flesh and blood even though that all seems quite strange to me.”

“It’s only…” Clara gathered her scattered thoughts. “It’s only that… where I come from, clockwork can’t talk.”

“Oh, of course it could, if only you had the right mechanics to reproduce the voices—”

“No, it’s not that the mechanics are too complex, it’s that, well… you seem to be able to think and react to me. Clockwork only does the same thing over and over.”

“That! Oh, that. Well. Yes. This place is different, you see. It’s impossible to make a dead thing here.”

“A dead thing?”

“That is what we call the poor crafts on the other side—dead things. That’s not really fair, I suppose, because they don’t know any better. They’re quite oblivious to the fact that they are dead things.” She wrung her pretty pale hands, hands Clara now saw as complex, perfectly attuned doll’s hands. “Oh, how to explain! You make a garden, it grows, yes? It is alive. But if you pick the flowers and make a bouquet, it is very pretty, but it is dead. You make bouquets on your side. Here, you make gardens.” She paused. “That’s a bit confusing because even the gardens here are more alive, you know. But I suppose it catches the heart of it.”

“And so a clockmaker, a craftsman… he made the woods here, and he made you?”

“Not the woods. The woods were here, before I was, a remnant from a daydream on your side, most likely. Probably a child—children are much better at that sort of thing.” She strolled toward a fountain, beckoning Clara to follow. The fountain was as she recalled it from an abbreviated stroll through the Jardin some weeks earlier, except this one was wider and shallower and, running in a ring around its lip, a vine of crystal flowers sprouted. Cups, she realized as they drew closer—cups set into crystal petals that could be plucked. She held one up—it was so delicate she worried she might crush it.

“Have a drink,” Olympia suggested. Clara had a brief moment of concern as she dipped the cup into the fountain—in her own world it would be quite unsanitary, and who knew what sort of magical danger might lie hidden here. Yet as she took a second glance, she noticed—the water was faintly lemon-colored and—she started—lemon-scented. “It began rather simply—years ago, I think, some little fellow playing on your side was thirsty and imagined the fountain made of lemonade.” Clara stared at her, and she laughed. “And it’s still here! Have a drink, then!”

She lifted the cup to her lips in wonder and tasted. The best lemonade, perfectly tart and yet tempered with a gentle sweetness, but more than that, it conjured instantly memories of picnics and a broad summer sun and the clank of ice in a tankard—memories she was not entirely sure were her own.

Olympia had explained the changes in her apartment, Clara realized—she had imagined it looking the way it looked in this world and, without meaning to, changed this world’s version of the rooms and furnishings. “Why him?”

“Oh, I haven’t any idea how that all works. Why a place gets fond of someone and they get to paint over it whatever they fancy—people who come later refine it, of course, or layer over it completely. And sometimes the whole thing goes inside out. You could change it, if you wanted. It’s easier to change things when you’re here.” She shrugged, then brightened. “Do you know ballet well? Perhaps you might finish our choreography!”

“I’m afraid I don’t know ballet well at all.”

Olympia’s smile faltered, but she recovered. “Or even come and be our audience again. We do so love an audience—I dance properly when wound properly, of course, but never as well as when someone is watching.”

“Of course, it was absolutely lovely—” A resonant bell tolled, startling Clara. Its bright peals reverberated under her feet, through her shoes, and sent a shiver up her back. Not entirely unpleasant, but uncanny, as though she were part of the humming cloche itself. “What is that?”

“Orleans, Beaugency, Notre-Dame de Clery,” Olympia answered in a singsong voice. “It’s the bells, of course.”

“Of course.” Clara set the crystal cup back into its nest of petals. “I—what time, do you happen to know, do the bells ring out?”

“Why, at noon!” Olympia laughed. “Fancy not knowing that. Vendome, Vendome,” she sang along with the dying echoes of the bells. Noon! Madame Boule would be expecting her for dinner soon enough, and she had no idea how to get back. “Not that I have much need of that sort of time. Musical time, now, is a different matter—oh, do you need to leave?”

Clara forced a polite smile. “I’m very sorry, but I do. But do you happen to know—that is, how do I go back?”

“And I thought not knowing the noontide bells was funny!” Olympia laughed again; Clara tried to tamp back the anxiety that had remained, until now, buried under wonder. “Well, it’s only”—Olympia hiccuped between giggles—“it’s only that the craftsmen make their keys themselves, or at least they used to—at the very least, they’re apprenticed and learn to use them properly! I’ve never heard of a craftsman who didn’t know how the key worked!”

“Keys.” Clara fished the magnifying glass out of her pocket. “I don’t suppose they work both ways.”

“How else does a key work? Don’t you lock the one side of the door with the same key as you lock the other?”

“I suppose,” Clara replied, “that you do.” Without thinking, she held the glass to her eye. The fountain, the Christmas trees, the shimmering sugared fruit, and Olympia vanished in a blaze of white light.

Chapter Eight

Clara blinked. she shoved the glass back into her pocket, realizing belatedly that she had just thrust herself through an invisible portal into one of the busiest gardens in Paris at the height of noon—and on a holiday, no less. The light still sparkled in her eyes, and she squinted, hoping she hadn’t appeared like a ghost in front of a crowd of onlookers. How could she explain a sudden appearance in a public park, she wondered, as the glare finally receded and her eyes adjusted.

She looked out into a silent and deserted Jardin des Tuileries. The first gray light of dawn was creeping between the topiaries. She took a hesitant step forward, then another. She was met with the ordinary Jardin in ordinary Paris, not a Christmas tree wood hiding a mechanical ballet. The fountains had been shut off for winter.

She understood quickly that the passage of time must be different between both Parises. She kicked herself for not noting the precise time she had tried the key, but resolved to do her best to figure out the ratio; she assumed, of course, on first glance that time must run more slowly on the “home” side and more quickly on the “other” side, but then realized she had no confirmation of the fact that it had not been, say, two days. Or weeks. Or even—stories of Rip Van Winkle came careening out of her memory—years.

Before she could frighten herself into wondering if a century had passed while she had been watching the mechanical ballet and sipping fountain lemonade, she stepped out onto the street. Unless very little advancement in technology had occurred, a century had not slipped by. Not even a decade, she ascertained, fairly sure that even ten years would mark an increase in the automobiles on the streets of Paris. A bell tolled, and then another—ordinary church bells this time.

Unless she had happened to stumble into another day known for bells at early morning Mass, it was Christmas. She had never felt compelled to go to church before, but this was an exception. For one, it would explain why she was wandering about outside in the last dregs of dawn. For another, it would give her at least an hour of anonymity in which to stop the whirling in her head. Saint-Germain was the closest church; she could hear its bells inviting all to Mass, and she accepted.

Like plenty of good Milwaukee families, the Ironwoods had attended the Gothic-esque Lutheran church downtown. She had thought the building imposing and grandiose at the time, stuffed in a pew between Louise and Mother while the choir intoned each step of the liturgy. The interior of this church disabused her of any notion that she had seen the height of church grandeur—and it wasn’t even one of Paris’s more famous cathedrals. She settled into a pew in the back, watching as droves of parishioners filed by her, realizing belatedly that she had certainly flagged herself as a tourist when she had failed to kneel and cross herself before entering the pew.

Fortunately, the Lutheran liturgy wasn’t so dissimilar to the progression of the Mass that, despite not understanding more than a few words here and there, Clara followed the kneeling, standing, and sitting. She didn’t even try to mouth the responses. Instead, she fell into deep thought.

Whatever she had encountered could only be described as magic.

Magic, therefore, was real.

A thin trickle of wonder bloomed into nearly uncontainable excitement. Magic is real. She stared at the polished wood of the pew in front of her, eyes unfocused as she let the strangeness, the beauty of that truth settle over her. Magic is real. Her hands quivered until she clamped them closed in her lap, but she couldn’t stop her smile, impervious to any attempts to wrestle her face into somber submission.

Focus, she told herself, putting perhaps excessive demands on rational thought to consider the evidence and conclusions of her discovery. She was very sure that she was not mad, and very sure that she had not experienced some hallucination or sleepwalking phenomenon. The whole thing had made a strange sort of sense. It was all quite logical, if you could accept the facts as they stood. Clara was very used to collecting facts and then applying them, and so she found, with some surprise, that she could accept the whole picture drawn by the individual facts of this situation with very little resistance.

There was an alternate Paris—possibly, probably, she considered, an entire alternate world—running congruent with the one she lived in.

Godfather had known about this.

Godfather, she swirled the idea around her mind like wine around the glass, knew about this. And not only that, he had wanted her to know, too. He’d sent her the nutcracker and prodded her into discovering the key. It would only be a matter of time, he must have wagered, until she would accidentally use it and slip into—what was she going to call the other place?

She shook her head. Alternate world nomenclature would have to wait. Godfather intended her to find the other place, and yet he had buried every clue she would need to do so. That, she reminded herself, was no surprise—Godfather never taught directly when he could make her teach herself through trial and frustrating error. And yet, how had he managed to avoid any hint, any mention of it for the many years they had spent together?

They had worked elbow-to-elbow for long days when she apprenticed to him, and he had never breathed a single word that suggested there could be a world mirror to theirs, full of wonder. Full of magic.

Or had he?

The priest raised his arms, and the congregation stood. Clara scrambled to her feet, but her mind was cast back into her childhood. She remembered a Christmas party, the tree trimmed in pink and burgundy ribbons that year, Louise in a brand-new dress, the grown-ups gathered around a bowl of punch, the children waiting for the cake to appear. Clara must have been ten—no, eleven. She remembered Louise’s lavender gown, sprigs of flowers and a wide sash, the length brushing her ankles, and the disappointment she had felt in still wearing a shorter child’s dress. “When you’re twelve,” her mother had said.

Eleven, just on the cusp of being not-quite-a-child, and yet far from being grown. Louise had seemed so old then! But when Godfather had asked if Clara wanted to hear a story, she had eagerly clamored for one. He had pulled the lake of dancing swans he had made down from the shelf—Mother always put Godfather’s complicated and quite breakable toys on a high shelf, making Clara occasionally wonder why he bothered making them at all, as no one really got to enjoy them.

Godfather set the swan lake on the table and peered at it for a long moment, until Clara drew close and gazed into it, too, wondering what she had missed in the depths of the mirror lake or in the variety of the swans, who each wore a crown with colored glass gems. Finally Godfather spoke. “Do you know what this is?”

“It’s a lake with swans, Godfather.”

“Yes, of course. But do you know what it is, really?”

“You made it—so it’s glass and metal and springs and wheels and—”

“Yes, yes, of course. That is what it is made of, but not what it really is.” Usually when she answered his questions incorrectly, even as a child, Godfather would begin to get cross. That Christmas Eve was different; perhaps that was why she remembered it so well. He knelt beside her and looked at the mirror lake and the swans from the same perspective she had. He wound the key on the back, and the swans moved in orderly, graceful arcs. “This is the pond in the park. The one where you feed the ducks.”

Clara looked at the lake again—the shape was familiar, a sort of squashed-heart shape that did follow the lines of the pond in the park. And the little palace on its shores—that was placed just where the bandstand was, only rendered here of white filigree and pink glass instead of brick and mortar. The path that wound around the pond—it branched in the same places, but it curved into flowers and spirals instead of ending at park benches.

“Except there are swans,” Clara confirmed as she gazed at the toy, “instead of ducks.”

“And much more besides. The lake is clear as a diamond, and you can see to the bottom, where it’s all paved with mother-of-pearl. The swans swim all day and practice their dance. At night they go to roost in the little pink glass palace—you can see inside, it’s all clear and clean and snug, and there is fresh golden straw every day for them to sleep on. On Sundays a girl comes down the path—it’s all made of mother-of-pearl, just like the bottom of the pond, you see—and collects popcorn for the swans to eat.”

“Popcorn! Where does she collect popcorn?”

“Why, from the popcorn trees!” Godfather laughed. “They are like our catalpa trees, with huge fans for leaves, and ancient-looking bark, except the bark, I think, is gingerbread. It smells like your mother’s recipe. And when they bloom—pop! Instead of flowers, it’s all popcorn balls.

“It’s all there, you see. If you find the right lens to look through.” And he’d twitched his nose so that his spectacles had waggled comically, and she had laughed, and thought it was a pretty story and nothing more.

It wasn’t. Godfather had made her a facsimile of the “otherworld”—yes, that would work for it, at least for now, she decided. The duck pond at the little park up the street really was a lake of dancing swans with a pink glass palace on its bank, and Godfather had seen it. She thought of all his creations—dead things, as Olympia had said, created in their own ordinary world, but also inspired, she realized, by the otherworld. His skill and craft were his own, yes, but he was granted another gift, the vision of the otherworld. The right lens to look through—that hadn’t been a pretty metaphor about imagination. He’d meant a very real magnifying glass hidden in the very real nutcracker they’d used to open walnuts a hundred times.

The congregation rose for the final benediction—they had received Communion while Clara had been thinking about popcorn balls for swans—and she blended into the crowd as they filed outside.

“Miss Ironwood!” She turned at the sound of her name, jarred to be recognized in the real world after her thoughts had been so occupied with the otherworld.

Madame Boule waved at her from up the sidewalk. “And you said you would not come for Mass—and this is dawn Mass, you are up early for one who did not mean to come!”

Clara felt sudden, vague panic—she couldn’t let anyone know about the magnifying glass or the otherworld. If nothing else, they’d think her mad. She was not used to lying—in fact, she’d always considered herself quite bad at it. “I woke up early,” she floundered. “And the bells, I couldn’t fall back asleep, but—”

“Oh, of course, and I am like a child on Christmas, too. I wake early, too excited!” Madame Boule laughed. “Now you must come home with me and help me make dinner, yes?”

“I’d be happy to,” Clara said, grateful for the promise of something practical to do while her mind twisted over itself with wonder.

In the run up to the 1900s World’s Fair Paris is abuzz with creative energy and innovation. Audiences are spellbound by the Lumiere brothers’ moving pictures and Loie Fuller’s serpentine dance fusing art and technology. But for Clara Ironwood, a talented and pragmatic clockworker, nothing compares to the magic of her godfather’s mechanical creations, and she’d rather spend her days working on the Palace of Illusions, an intricate hall of mirrors that is one of the centerpieces of the world’s fair.

When her godfather sends Clara a hideous nutcracker for Christmas, she is puzzled until she finds a hidden compartment that unlocks a mirror-world Paris where the Seine is musical, fountains spout lemonade, and mechanical ballerinas move with human grace. The magic of her godfather’s toys was real.

As Clara explores this other Paris and begins to imbue her own creations with its magic, she soon discovers a darker side to innovation. Suspicious men begin to approach her outside of work, and she could swear a shadow is following her. There’s no ignoring the danger she’s in, but Clara doesn’t know who to trust. The magic of the two Parises are colliding and Clara must find the strength within herself to save them both.