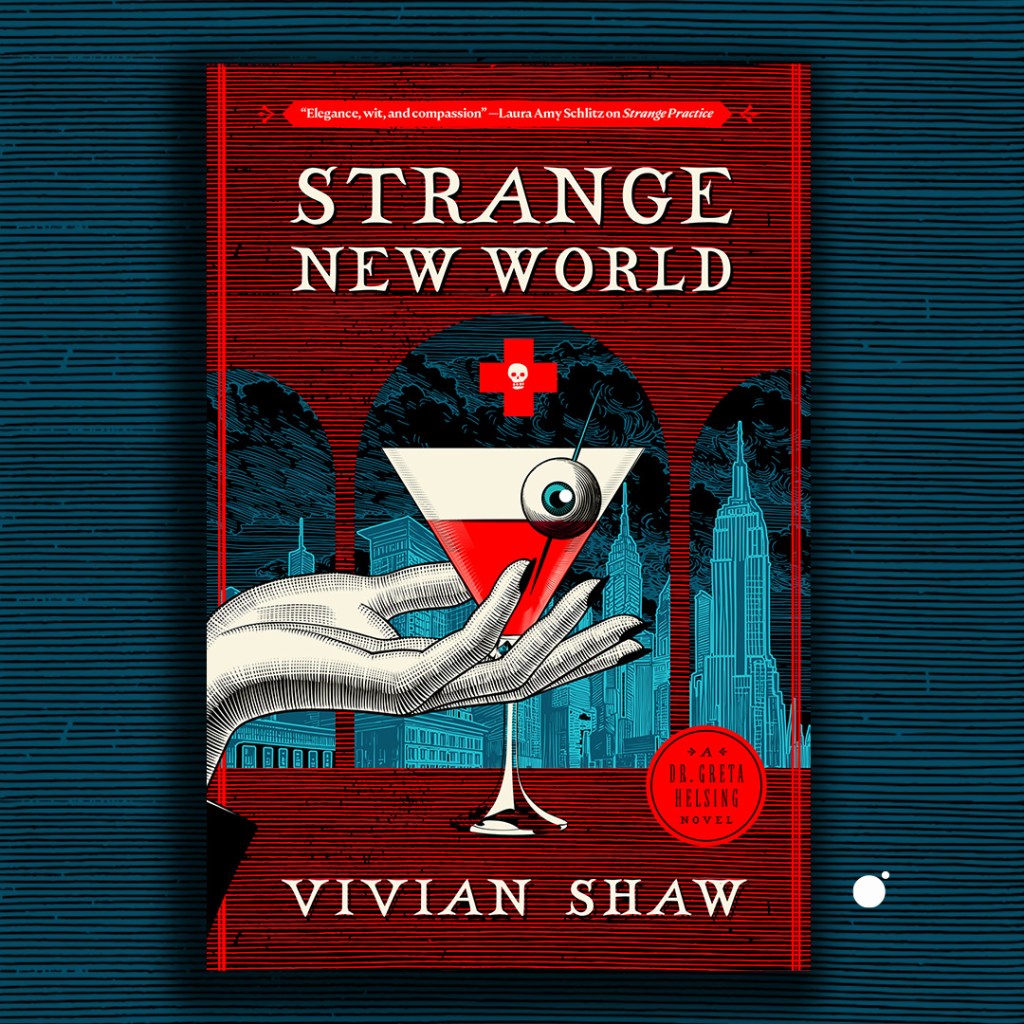

Excerpt: STRANGE NEW WORLD by Vivian Shaw

In this witty conclusion to a delightful fantasy series finds Greta Helsing, doctor to the undead, facing the latest and strangest challenge of her career… accompanying an anxious angel and a sullen demon on a road trip across America.

Read an excerpt from Strange New World (US), available now, below!

CHAPTER 1

Alessio’s Italian Restaurant, the Bowery, New York City

Nobody could remember exactly when this place had first opened; it had stood on the corner of Bowery and East 3rd for as long as people’s memories generally lasted in this particular neighborhood, although it had been apparently shuttered for a good twenty years. This past spring it had opened up again, under new (or possibly old-but-new-again) management, and was doing good business on a street where practically every block featured at least one red-sauce joint. Perhaps lighter on the garlic than others, but generally unremarkable.

It was midnight; the place was closed, but a dim light was visible behind the blinds in the front windows. A very curious person might have sidled up to the window to see if they could peek through the gap and get a look inside; an even more curious person might have gone around the back to listen at the door of the kitchen, but neither of them would have stayed curious for long. The little black bulbs of security cameras studded both the front and back of the building like architectural pimples, keeping a close eye on passersby.

That incautious person might have heard a few muffled curses from inside, followed by a nasty bubbling scream. The scream was choked off into more cursing.

“—shitting mother of fuck, Jesus, get your hands off me,” whoever it was spat. “I told you I didn’t see nothing—ah, fucking Christ that hurts—”

“So you said,” another voice cut in: this one held both authority and the hint of a lisp. “Mario, put some of that rotgut inside him instead of in the hole; it might have a more salutary effect. One more time, Radu. Slowly.”

The three men were in the restaurant’s kitchen, lit only by the green glow of the EXIT sign over the door and the sodium-vapor streetlights outside; apparently what they were doing didn’t require a lot of illumination. The unfortunate Radu, stripped to the waist, was sitting on a café chair turned around backward, his face buried in his folded arms on the chair’s back. Mario, as directed, splashed some of the cheap vodka he’d been pouring over a wound in Radu’s back into a glass instead. Slow dark blood trickled from the wound, which looked ugly even by the limited light available: its edges were puffy, swollen as if whatever had made it had been coated in something corrosive.

Radu took the glass, knocking back the shot in one gulp, and coughed explosively; when he could speak again he sounded a little more steady. “Like I said. Didn’t smell anything weird, just ordinary humans, I didn’t think anything of it, minding my own business when suddenly this fucking thing hits me in the back like a fucking icepick, and by the time I can turn around there’s nobody there, not even the goddamn bums, everybody’s split the scene. Fucking dart hurts like I got shot, plus I have to puke my guts out, and when I’m done doing that, all I can do is get my ass back here for some fucking back-alley surgery—fuck, Mario, gimme another drink, I feel like shit—”

Mario obliged, and poured another splash of vodka from the plastic handle over a linen napkin, dabbing it at the hole in Radu’s back. “I got it all out,” he said. “Thing had some kinda shit on it, must be what’s makin’ him sick, but I got the pieces outta him, Mr. Contini. Saved ’em in case you want someone to look at it or somethin’.”

“Thank you, Mario,” said the third voice, presumably Mr. Contini. “Your presence of mind is admirable. Radu, you said you smelled humans in the area before the attack. Were they wearing perfume or cologne, or in need of a shower? Any details would help.”

“Just humes,” said Radu, swallowing his second drink. “Maybe coulda used a shower, but not real funky. No perfume or nothing. Smelled like—floor polish, that pink liquid-soap shit they put in public bathrooms. Bad food.”

“Bad food,” repeated Contini.

“Soup-kitchen food. Shit you make in those big old vats, cheap noodles and sloppy joes, that kinda stuff.”

“Not the scent of people living their best lives,” said Contini. “Mm. Did you get any whiffs of anything else once the thing hit you?”

“Couldn’t smell a fucking thing, I was too busy hurling,” said Radu, sounding as if he might repeat the process in the near future.

“Here’s the thing I dug outta him, Mr. Contini,” said Mario, offering a folded-up napkin wrapped around something. “Smells kinda like herbs and metal to me, but I ain’t so great with smells since last time my nose got busted.”

“I see,” said Contini’s voice, and its owner moved out of the deeper shadow to take the handful of crumpled linen: tall and very thin, with high shoulders and long fingers made longer by clawlike nails, the green EXIT light sliding over slicked-back black hair. The eyes were invisible in deep-sunken sockets, except for two sparks of reddish light. “Well. I suppose you’d better stay here tonight; try not to be sick on the floor if you can help it. Mario, go ahead and lock up once you’ve put a bandage on that, and then call around to warn people there’s someone playing stupid games in the city. I’ll be in my office. Don’t bother me without a very good reason indeed.”

“You got it, sir,” said Mario, glancing at his colleague, and grabbed for the trash can just in time.

Erebus General Hospital, Dis

Behind his desk, Dr. Johann Faust’s floor-to-ceiling office windows looked out over the central plaza of Dis with the shimmering opalescent flames of Lake Avernus in the background. The view was largely wasted on him; as medical director of the Erebus Health System he was either too busy in the hospital itself to spend much time in his office, or on video calls with the windows opaqued behind him. Today, however, he had the glass set to transparent and had rolled his chair a little to the side so as not to block the view.

On his desk’s big central monitor, an angel—winged, androgynously beautiful, identifiable from a demon only by the halo and the blank golden eyes—sighed. On closer examination, it looked rather more tired and worn than one might have expected from the host of Heaven; there were shadows underneath those golden eyes, and the beautiful features sagged a little. Behind it was a wall of pearl white, with no windows whatsoever.

“You get used to the view,” Faust said. He looked rather like the woodcuts: stocky, not so much fat as solid, bearded, wearing a dark velvet robe trimmed with fur rather than a doctor’s white coat; he wasn’t seeing patients this afternoon. “The burning lake is a bit much to ignore at first, but you do stop noticing after a while.”

“I wouldn’t want to,” said the angel, sounding wistful. “Something that beautiful should never be taken for granted—but I would find it a distraction, I admit.”

Unlike some of the angels Faust had encountered, this one lacked the constant expression that suggested something in its vicinity smelled regrettable; there was a certain rueful, self-aware set to its otherwise anonymous features. It was also the only one of the archangels with whom Faust had any desire or patience to engage in conversation, because it was the closest thing Heaven had to a physician. He didn’t envy that position one tiny little bit: the badly-hidden exhaustion on the angel’s face spoke of an endless round of frustrations. “You ought to knock off for a bit,” he said, characteristically blunt. “Go to the celestial equivalent of the Spa and soak in holy water or whatever it is you do, get some actual rest, Raphael. You’re looking a bit seedy, and that’s a professional medical opinion.”

“We haven’t got a spa,” said Raphael, not without a tinge of regret. “We shouldn’t need any such thing, you understand. That sort of sybaritic pleasure-seeking is supposed to be for your sort. We’re above physical infirmity.”

“It says so in the handbook, then?” said Faust. “‘How to Angel: Be Constantly Exhausted but Not Complain’?” Actually, that did ring fairly true, he thought.

“I’m not exhausted,” said Raphael automatically, and then put a hand to his face. “All right, perhaps I’m a little tired, but it’s only because there’s much more work than usual. Since the—the reset, and the signing of the Accords, and the—collaborative initiative. All the exchange work-gangs here and down in Hell. It must be a great deal more work for you as well, surely?”

“That it is not,” said Faust, “for the clear and simple reason that I’ve got delegation going on, unlike you lot. I don’t have to do all the work myself. The hardest thing we’ve had to deal with since the Accords has been managing the allergic reactions—some of it’s just sniffles, but I’ve had several people need emergency care—and the high-energy mirabilics labs are working on that as we speak. We’re getting some interesting results from Lake Avernus water run through the scanner, based on what I had to use for plasma for your angels during emergency surgery.” He tilted his head. “Come to think of it, what are you doing up there about allergies with the exchange work-gangs?”

“Masks,” Raphael said, sounding as dolorous as he’d ever heard an angel. “And lots and lots of nectar for the angels, but we haven’t got a thing other than masks to help it in demons, the poor things. We, uh, tried the nectar, despite my strong recommendation against the idea, and it—really didn’t go well at all, I’m afraid.”

Faust snapped his fingers. “Two months ago. Right? We got a group of demons in the ER down here with acute GI distress, looked like they’d ingested something mildly corrosive, didn’t want to talk about it.”

“I am so dreadfully sorry about that,” said Raphael unhappily. “I did submit an official report to the Council beforehand to point out that giving demons any food or drink from Heaven was probably not going to do them any good at all, but that was interpreted to be a, a xenophobic and defeatist attitude, and Gabriel came and counseled me about it. And how we all need to pull together to fulfill the Accords and there’s no room for negativity.”

“Fuck’s sake,” said Faust over the angel’s wince. “It wasn’t really that much of a problem, gastric lavage with lake water and some empirical treatment sorted them out nice and quick, but do your lot really refuse to listen to the voice of reason that much?”

Raphael looked so miserable that Faust had to hold up a hand. “Never mind. Not my business, my circus, or my monkeys. Point being, soon as I get anything useful out of the labs that works on our end to knock down the allergic reaction—and won’t set it off on your end—I’ll send it up to you at once. By the pallet-load if necessary.”

“I don’t know,” said Raphael, “I don’t think Gabriel would like that, but maybe he could be convinced?”

Right after the… events… of the recent post-apocalypse reset, which Faust didn’t want to think about in much detail, there had been reason to believe that the angels responsible for bureaucratic management in Heaven had perhaps had their horizons broadened, but it sounded to him like they had settled directly back into their old ways. The official infernocelestial Accords that had been signed by Gabriel and Samael after the fighting was over, witnessed by the massed hosts of both Heaven and Hell, included a clause decreeing that both sides should actively collaborate in joint projects to accelerate the rebuilding process in Heaven. Faust had said a great number of bad words in German when he’d read that particular subsection. He’d known perfectly well why it was in there, after the blank horror of the war itself and the clear and present need for Heaven and Hell to work together to prevent any such thing happening again, but that didn’t make it not intrinsically stupid: philosophy and good intentions were all very well, but they didn’t trump physiological reality. Angels and demons in the full manifestation of their power were unavoidably allergic to one another, and nothing was going to make angels in Hell and demons in Heaven not suffer the physical repercussions even if it sounded good on paper.

He’d said so to Samael, in the Devil’s white-on-white office, leaning with his hands flat on the white-wood desk: If I haven’t made it sufficiently clear, my lord, the clinical reality here is that this is not going to fucking work out just because it’s narratively convenient and people want it to, I can’t fix the basic nature of the goddamn universe to fulfill political goals, and just for a moment felt a flicker of mindless atavistic fear as Samael’s eyes had gone from brilliant butterfly blue to blank scarlet, lid to lid. It was the worst argument they had ever had—Samael had never refused to listen to him before when he’d pointed out reasons why something wasn’t going to work—and even thinking about it now made Faust’s stomach feel unsettled.

Thank you for your clinical input, Doctor Faust, the Devil had said, enunciating. You may go, and for the first time since he’d shaken hands with Mephistopheles all those centuries ago, Faust had been afraid of his employer.

(He had known, of course, that Samael knew as well as he did that this was impossible, no matter what they tried to get around the physical reality of it. He’d just hoped Samael could unmire himself from politics enough to point that out to everybody else.)

He was not afraid now; he was frustrated. And Raphael, poor bastard, had to deal with the frustration of an entire divine bureaucracy trying to make him do the impossible without any of the resources Faust had to draw upon. Nothing could prevent the reaction. It was built into the nature of the universe itself. You could hope to ameliorate the symptoms of that reaction, but you could not prevent it from occurring. As long as demons were helping with the debris-removal and construction gangs in Heaven, or angel volunteers were helping organize library stacks in Hell, this would be a problem.

As long as…

“You know what,” he said, slowly. “I’ve just had a brilliant idea. Again.”

“Oh?” said the angel, blinking.

“So we know that demons in Heaven and angels in Hell are viciously allergic, yes? Well, what about if they don’t swap places? What if they work together on the Prime Material instead, neutral ground? It’d be interesting to see if the reaction is still as intractable when the individuals are no longer affected by their physical location magnifying its intensity. We know from the surface operatives that at least limited and periodical contact—when they have coffee together or occasionally meet to talk—doesn’t seem to trigger it, but what if we increased the direct, prolonged exposure to one another in a relatively neutral environment?”

“You mean—send an angel and a demon to Earth specifically to work closely together?” said Raphael, blinking again before a smile like sunrise broke through the visible fatigue. Faust was briefly stunned by the beauty, glancing hurriedly away. “They could… further the missions set out in the Accords,” the angel said, as if realizing this out loud. “Couldn’t they?”

“They absolutely could,” said Faust, still seeing afterimages. “And provide both of us with valuable data in the process.”

“They’d have to work closely together,” said Raphael. He now appeared faintly lit from within. “To… collaborate. Setting aside differences. And achieve some sort of common good in the mortal world. As an example of, of infernocelestial bipartisanship.”

“That, too,” said Faust, reflecting that as a human he himself had had a much easier time learning how to be a medical administrator than an archangel must have, even one like Raphael who’d occasionally had a thought cross their mind. “Get ’em to build a house together or something. Be all constructive. We’d need a pretty young and enthusiastic demon for the role, of course. I’m sure we can find someone.” Fastitocalon was always complaining about his interns; maybe one of them could be pressed into service.

He couldn’t quite read Raphael’s expression, but he could have sworn for a moment that something quite like glee flickered across his lovely features and was gone. “And we’d have to find a young and driven angel,” Raphael said. “Who really is passionate about things. Who could bring energy to the project. Wouldn’t we.”

“Just so,” said Faust. “Look, why don’t you have your people start looking for potential candi—”

“I’ve got one,” said Raphael, very fast. “I’ve got the perfect candidate.”

And you want to get him the hell out of Heaven posthaste, Faust thought, not without sympathy, wondering what exactly this candidate had done to get up the angel’s nose; Raphael was a very great deal more patient than Faust himself had ever managed to be, even when he’d been alive, but apparently even archangels had limits. “Excellent,” he said out loud. “I’ll ask around, see if we can find someone suitable on our end to volunteer. They ought to have some sort of specific project to work on while they’re paired up, I’ll have to think about it—probably building houses isn’t quite the ticket, but I’ll come up with something.”

“Do,” said Raphael. “I think it will be of extreme use to everyone involved. Our candidate is… to some extent trained to work in healthcare, but he is very inexperienced and would need professional oversight.” There was a delicate weight on professional that said a number of things at once; Faust wondered again what the mysterious angel had done, and decided he didn’t want to know.

“I’m not up on my roster of surface operatives,” he said, “that’s all Monitoring and Evaluation, but presumably someone up there would be capable of taking on a couple of inexperienced beings and provide professional oversight—”

He snapped his fingers again, the idea coming to him all at once. “No. Even better. We needn’t necessarily place them with a Hell surface op at all; I’m acquainted with a human physician on Earth, a personal friend of the archdemon Fastitocalon, who might possibly be able to help figure out something vaguely useful to do with them. She was of some use down here in the worst of the fighting and I’d trust her to keep basic order between an angel and a demon for a bit.”

“Your arches have human friends?” said Raphael, blinking. “Is that strictly ethical?”

“We’re Hell,” said Faust, with a less-than-pleasant grin. “We approach ethical from a somewhat unorthodox direction.” He felt ever so slightly guilty about dropping Greta Helsing in the soup, but she’d think of something. Of that he had no doubt. She was good friends with Fastitocalon, wasn’t she? Being involved in infernocelestial politics shouldn’t really pose much of a challenge for someone who knew as much as she undoubtedly did about the subject, and she’d done a pretty decent job of emergency surgery with zero experience to back it up; he thought she’d do at least as well keeping an angel and a demon in order when the world wasn’t ending all around them.

“Let me make some calls,” he said. “I’ll be in touch.”

Harley Street, London

The difficulty with cosmetic reperfusion for Class A revenants, colloquially known as zombies, was not the actual physical drainage and replacement of the old embalming fluid; that was easy, if mildly unpleasant. The real challenge was getting your tints right.

They’d come a long way since the “suntan” and “natural” dye formulations of the sixties. Back then, zombies had had to make do with varying shades of orangey-pink if they didn’t want to go with formaldehyde grey; these days you could mix up a custom blend of hues to add to the embalming fluid, and it was somewhat rewarding for the physician as well as the patient to watch the color change as the dyed fluid perfused the tissues.

Greta Helsing was very good at it. Greta Helsing had a state-of-the-art Porti-Boy embalming machine that could pump a full dose of fresh embalming fluid through a patient’s body in about half an hour, start to finish, and she was extremely skilled at mixing her dyes to get the right color balance in the finished tissue. She hated doing it, because the formaldehyde—even in her well-ventilated procedure room—gave her a foul headache. At least this morning’s patient had left well satisfied with the results of his procedure, brand-new trocar buttons glued in and sealing the incisions through which the fluid was pumped and drained, and she didn’t have to do anything else complicated for a little while.

Her phone rang for the fourth time in half an hour while she was still rootling around in her current enormous handbag for the ibuprofen, and it took her a moment to winch her professional smile back into place before picking up. “Greta Helsing,” she said, and gave in, briefly making a horrible face that no one but her office wall could see.

“Greta? Arne Hildebrandt. Have you got a moment?”

Hildebrandt was in charge of one of the major labs in Göttingen doing research on supernatural medicine, a sort of grey area between the ordinary world and the one her patients inhabited, kept safe by a blanket of obfuscation that to the casual eye merely indicated normal-type biological research. He’d been instrumental in publishing one of her early papers on mummy medicine; she considered him a valuable colleague.

“Hello, Arne,” she said. “What’s on your mind?”

“Well, it’s a little hard to explain. It’s our records,” said Dr. Hildebrandt. His German accent was noticeable but not distracting. “We’ve been going through last year’s lab records prior to moving everything to a new building, and there’s this… discrepancy no one can seem to explain.”

Greta’s talking-on-the-phone smile did not so much falter as diminish, like a radio with the volume slowly turned down. “What sort of discrepancy?” she asked.

“It’s very subtle,” said Hildebrandt. “But it seems that halfway through one day’s transcription, every single record changes as if one author left off and another suddenly took over. I could ignore it if it was just one or two documents, but it’s every single record. All the papers. Every computer file. Parameters ever so slightly altered. No one knows why.”

Greta shut her eyes, the headache clanging louder than ever. She’d been afraid of this; she’d hoped like hell that it wouldn’t happen, but on some level she’d always known it was just a matter of time.

Almost every human on the planet lacked conscious recollection of the moment last year when the entire world had undergone an elemental change: an apocalypse averted, a universe’s parameters reset. Only creatures made largely out of magic and memory itself, like mummies and certain other monsters, or people who hadn’t been on Earth while the crucial bit happened, like Greta, had any clear recollection of that particular moment in time.

“It’s like some sort of—I don’t know, pressure-wave went through and moved every single recording instrument, every measurement, every thing, ever so slightly, all at once.” Hildebrandt sighed. “I want to think of this as just an aberration—a seismic tremor, or something, but I can’t make it work with the evidence we’ve got.”

Of course you can’t, she thought, pressing her fingers to the rim of her eyesockets. You’re sometimes deeply annoyingly smarter than the majority of humans, and you are a scientist, so you are very clearly not going to let this go, and I have no idea what the hell I’m cleared to tell you. She didn’t even know what the official Hell position was with regards to information the humans were allowed to share; Faust had only given her limited information about the science of magic because she’d asked him, but she was pretty sure that was supposed to go no further without official permission.

“… Greta?” said Hildebrandt. “You still there?”

She opened her eyes to find herself staring at the dog-eared pile of textbooks on her office credenza, and turned her attention back to the phone. The books had titles such as Principles of Mirabilics, fifteenth edition, and Applied Mirabilics: An Introduction. “I’m here,” she said. “And—maybe I might have some idea about what’s behind the discontinuity, but I can’t be sure until I talk to some colleagues of mine.” Or ask them what I’m allowed to say.

“Well,” said Hildebrandt, sounding a little puzzled. “Thanks, I think?”

“Let me get back to you, Arne. I won’t be long.”

Monitoring and Evaluation Director’s Office, Dis

Fastitocalon put out the morning’s third cigarette and stared at the man sitting across his desk, fur-trimmed robe and floppy hat not much changed from the day he’d arrived in Hell several centuries ago. Over the years Fastitocalon had spent a great deal of time glowering at Faust, one way or another, while the doctor lectured him or told him to do painful things or—occasionally—reassured him, but this might be the first time he’d ever been on this side of a desk from Samael’s personal physician and the medical director of Erebus General. He’d only had this particular desk for a few months, but it was still a tiny flicker of pleasure to recognize each first time he experienced something as an actual archdemon instead of a third-rate excommunicated ex-accountant with chronic bronchitis and melancholia. Going from onetime employee to running the entire Monitoring and Evaluation department, in charge of the surface-operative business of keeping an eye on the Prime Material plane, was still a little difficult to fit inside his head; he wasn’t entirely sure he wanted to lose that repeated sense of wonder.

Faust looked right back at him and did not react at all when Fastitocalon very deliberately reached for his cigarette case, extracted another Dunhill, and lit it with a fingertip. “Run this by me again, slowly,” he said, blowing out a thin quill of blue smoke.

“I,” said Faust, with large pauses, like a British tourist trying to get a foreigner to understand English, “want your friend, the human doctor, to drive an angel—and a demon—and presumably a selection of ancillary people—around America—in a bus.” He eyed the burning cigarette-tip. “The angel’s some sort of terribly keen orderly or intern or something who’s apparently driving Raphael nuts, and I’m sure we can find an equally annoying demon counterpart to send up there with it; possibly you can recommend someone who would benefit from the experience. The point of this entire endeavor is to fulfill the very particularly idiotic bit in the Accords that goes on about infernocelestial collaboration and bipartisanship. By doing field research.”

“Yes,” said Fastitocalon, “that was more or less what I thought you said. Field research on supernatural creatures and their various ailments?”

“Précisément, Director. I am told this will be handled by External Affairs through a major European university’s coffers, under the guise of an ordinary research trip. All Helsing needs to do is stop the angel and the demon biting bits off each other or pushing each other in front of large vehicles, record how they are physically affected by being in the other’s presence—mostly this whole business is actually research to find out what the hell happens when you get them interacting on the Prime Material rather than Heaven or Hell so nobody goes into anaphylaxis—and do a bit of doctoring on the way.”

“‘Record how they are physically affected,’” said Fastitocalon.

“Record with scientific detail,” said Faust, nodding seriously. “She need not draw diagrams, you understand. But in-depth discussion of how they interact is to be desired. One can cling to a faint hope that actual data might prompt the powers that be to revisit that section of the Accords.”

Fastitocalon lost the battle and burst out laughing, passing a hand over his face. “I am so enormously glad I am going to ask her this over the phone, Faust. Not face-to-face.”

“I am so glad,” said Faust, getting up in comfortable triumph, “that it is you asking her, and not me.”

London

It was already getting on for full dark when Greta locked up the clinic at five-thirty, carrying several heavy files with her, and went to meet her ride home. This time of year there was no desire to linger and watch the golden light of evening slant its way across the river or warm the ancient stones of the city: she was cold, she was hungry, she had a filthy headache, and she wanted to go home, damn it all. The conversation with Hildebrandt had done nothing but engender a general sense of dread regarding what the hell she was allowed to say and to whom.

Ordinarily she’d have been able to stay at Edmund Ruthven’s Embankment mansion. She’d spent a lot of time there recently, one way or another, and she’d finally escaped the lease on her horrible little Crouch End flat by dint of throwing Ruthven’s money at the landlords and never looking back, but Ruthven and his partner Grisaille were in Romania. With Count Dracula and his latest ward, ten-year-old vampire Lucy Ashton, whom Ruthven and Grisaille had housed and sheltered for a few somewhat-complicated days this spring.

Lucy was an orphan who had been turned by a thoroughly unscrupulous American vampire, who had subsequently been tracked down and killed by Dracula’s people, and was now living her best unlife in the luxury of the Voivode’s castle learning how to turn into bats and wolves and mist and not having to put up with the vagaries of the English foster system. Ruthven had had conniptions over the entire process of trying to find somewhere for her to live before the Draculas had offered their home, but he seemed to have regained his general suave self-possession and jumped at the chance to go and visit with the family.

Greta rather envied every single one of them.

The demon giving her a ride to Varney’s country house was supposed to meet her at the end of Harley Street in the Cavendish Square park, a little circular oasis of trees and grass in the middle of an expensive chunk of city, and normally he was waiting for her to get there—she did try to be on time or at least text him if she was running late—but there was no sign of him anywhere on any of the benches they usually used for rendezvous. It wasn’t entirely unheard-of for Harlach to be late; generally he was about as good as she was in terms of texting ahead to let her know he’d been held up, but her phone was blank and clear.

Greta sat down crossly on a bench with her files in her lap and waited. It came on to rain.

Ten minutes late, she thought, checking her watch. Another five and I’ll text him.

Another five and I’ll text Varney so he doesn’t start to get concerned. It was very much not like her to be late home to Dark Heart House without letting him know; it wasn’t as if she had to deal with traffic. She wanted to be home so she could talk to Varney about the bloody, bloody discontinuity problem and what the hell she was going to tell Arne Hildebrandt.

The rain intensified.

Another two—

“Greta?” It was Harlach, hurrying out of the darkness, hugging his coat tightly around him, soaked and shivering, his face very white in the dim streetlamp illumination. “Lady Varney—I’m so sorry I’m late, are you ready—”

Fuck, she thought. He didn’t look anything even close to okay, and it had been months since she’d got him to stop calling her Lady Varney. She didn’t know him too terribly well; in her experience Harlach was pale at the best of times, his dark curly hair and heavy eyebrows and lashes giving him a (hopefully) unintentional Byronic air, but right now he looked grey in the flat streetlight, his hair wet and black. Grey in a way she hadn’t seen for several months, since her last encounter with the demon Fastitocalon. “Yes, of course,” she said, getting up, the files tucked under her arm. “What happened? Are you all right?”

Harlach just reached for her hand, and his fingers when they curled around hers were warmer than they should be, given the night’s chill. “Hang on,” he said, and the world went blank and brilliant white.

She had never liked translocation but she had to admit that reducing a multi-hour commute to a matter of seconds was definitely worth the brief disorientation. Cavendish Square vanished around them, and in the space of a few heartbeats that brilliant whiteness was fading to disclose the familiar terrace of Sir Francis Varney’s country seat: Ratford Abbey, generally and romantically called Dark Heart House for the sake of the copper beeches surrounding the old mansion. It wasn’t currently raining in Wiltshire, for which she was vaguely grateful.

Harlach stood beside her, still breathing hard; now he was wheezing faintly, his hand very warm in hers. Greta made a decision, pushing aside the worry over Hildebrandt’s question for now. “Come inside,” she said. “You don’t look at all well. You can have a drink and tell me what the hell is going on, if it happens to be something I’m in any way cleared to hear, and I’ll look you over properly.”

“… if you insist,” he said, pushing the wet hair out of his eyes, capitulating much too quickly. He was still wheezing, very pale, brownish crescents under his eyes, and he let her draw him toward the warmth and safety of the house. She’d never seen him like this in the half a year he’d been taking her to and from her London clinic; he’d always been the kind of suave, urbane, slightly overdressed type of chic you associated with surface-operative demons. This version lacked his usual polish.

“Come on,” she said, and opened the French doors leading into the blue drawing-room, into warmth and light and safety.

Sir Francis Varney was reading the newspaper in one of the large squashy armchairs pulled up to the fireplace. His ward Emily’s stacks of veterinary textbooks and notes and Coke cans were not in evidence: Emily had gone off for a week with some friends to climb mountains in Wales, of all things, and the house felt much larger and emptier without her. When Greta and Harlach came in, Varney first smiled and then put down the newspaper, looking concerned, and got up.

“Good God,” he said, staring at Harlach. “You’re drenched—was it raining or snowing or couldn’t it make up its mind?—Here. Have a drink.”

“I’m quite all right,” Harlach said, not sounding it, but he took the glass Varney pressed into his hand. “Just. Something of a shock.”

Varney flicked a glance to his wife, who was putting down the stacks of records she’d brought on the credenza, and both of them shared a single thought: What in London could possibly shock a surface-operative demon, and then Do we want to know?

Harlach swallowed half the brandy in his glass and coughed violently, setting it down on a little rosewood table, and when Greta offered to take his coat he shrugged out of it with a noticeable wince. “I’m sure it’s nothing,” he said, still wheezing slightly.

“It’s obviously something,” she told him, going to hang the coat up to dry. “Sit down and get your breath back, and then tell us what’s going on.” She couldn’t help thinking again how much different the Harlach she sort of knew was to this white shaking creature, and pushed away a thoroughly annoying spike of impatience. He’d tell them if he wanted to tell them, and it wasn’t necessarily any of her business except inasmuch as she wasn’t a hundred percent sure he could manage the return journey to London in his current condition.

Harlach, dazedly, slipped into a chair, unconsciously pressing his chest. His shirt, thus revealed, was black as well, obviously expensive. “I’m so terribly sorry,” he said. “Entirely letting the side down. But I… something jumped out at me, I don’t know where it came from, and I think it must have… thrown something at me? Something sharp?”

Varney hissed. “Are you hurt? Did it scratch you?”

Harlach lifted a shaking hand to his shoulder, pushed aside the collar of his (soaking-wet) Armani shirt, and his fingers came away red. He looked from them to Varney and Greta, eyes huge in his white face.

Fuck, thought Greta, meeting Varney’s eyes over the demon’s head, and slipped into her calm talking-to-patients voice. “Fetch my bag, would you, Francis, the big one, by the mud-room door. It’s going to be all right, Harlach. Just try to relax—finish that brandy—and I’ll have a look and sort you out.”

Neither she nor Varney could shake the mental image of a quite different drawing-room with a different creature laid out on a couch, suffering from a poisoned wound. Harlach didn’t look anything like as awful as Varney had on that night years ago, but he clearly wasn’t well, and she wanted a closer look at his bleeding shoulder. While Varney fetched her bag, she went to wash her hands before pulling on a pair of nitrile exam gloves.

Harlach was still very white, but beginning to be flushed high on each cheekbone, breathing audibly, and she couldn’t help thinking of that previous poisoning incident even as she had him ease the fabric down over his shoulder to expose the wound—and then let out her breath in a sigh of relief. It wasn’t even close to the cross-shaped stab wound that had brought Varney half-collapsing to Edmund Ruthven’s house. It was, in fact, just a scratch, but a bad one that was puffing up angrily and much too red and hot: something in the wound was irritating him.

“Right,” she said. “This isn’t very nice but I ought to be able to sort you out quite quickly, Harlach, and then you can tell us everything you remember.”

“There isn’t much,” said the demon, his eyes closing. “Just… I was on my way to come pick you up and something in an alley just jumped out and… threw something at me, or shot it—I wasn’t paying attention, I was on my phone—and it got me in the shoulder. I couldn’t see who’d thrown it, whoever it was had gone, and by the time I got to Cavendish Square to meet you I was unavoidably late.”

“Never mind late,” said Greta, taking a thermometer out of the bag Varney had brought. “Under the tongue, please. And you’re sure it didn’t scratch you anywhere else?”

He shook his head, and obeyed: 100°F, not fantastic, but not terribly dangerous for a demon. Greta got out sterile saline, disinfectant, antibiotic salve. He didn’t seem to be having worse difficulty with his breathing, at least, although she didn’t like the sound of it. “Varney, could you fetch me a towel? Thanks.”

She looked closer at the puffy, swollen scratch: yes, something still in there, tiny fragments. That swelling, plus the shortness of breath, told her she needed to get whatever it was out of there. Hadn’t the fucking Holy Sword people been sorted out, as Samael had put it? Were there now copycat idiots of some kind running about cutting holes in demons for the sake of eternal salvation, or was this just—terrible luck? Wasn’t the whole bloody reset supposed to have done away with disturbances like this?

One thing the past several years had taught Greta was that one made one’s own luck, by and large. Varney returned with a clean towel and a couple of her pairs of forceps still drying from the isopropyl he’d soaked them in rather than boiling them for several minutes, and she had to smile, remembering the moment when Edmund Ruthven the vampire had brought her instruments neatly arranged on a tray. She’d said Since when are you a scrub nurse, and he’d told her he had driven ambulances in the Blitz and that there was more in heaven and earth, Horatio.

He’d been right about that. Greta took the forceps and bent over Harlach’s shoulder while Varney held the light for her. Yes: a couple of tiny fragments of something deep in the scratch, the flesh almost too swollen to see them. “This will hurt,” she told Harlach. “It’ll be over soon, but it will hurt.”

“Understood,” he said between his teeth, and she bent closer and reached into the shallow wound to pluck out the residue, whatever it was. Varney, to his eternal credit, had brought her a clean saucer along with the forceps, and she straightened up and dropped a couple of tiny shreds of metal onto the porcelain.

Harlach had held still with visible effort throughout the nasty little operation; now she could irrigate the wound to clear any residue, and cover it with antibiotic salve, close it with a couple of Steri-Strips, and sit back on her heels. “There,” she said. “I’ve stopped, and you ought to feel much better soon, Harlach.”

“Thank you,” he said, eyes still shut. His breathing wasn’t what she’d call great but there was quite a lot less of the wheezing effort he’d demonstrated earlier, and he wasn’t pressing his chest. It really did look like that might have been some sort of allergic reaction to whatever she’d taken out of his wound. “I do… very much appreciate it, Doctor.”

“You’re staying here tonight,” she said, “we’ve got loads of spare rooms; don’t worry about a thing.”

Harlach nodded after a moment. “Can you lean on us long enough to get you upstairs?” she said.

“I can walk,” he said, and pushed himself upright, went grey-green, and nearly collapsed into Greta’s arms. He was shaking. “—Ugh. I’m sorry. Apparently I can’t walk terribly well at present—I really am so sorry about this—”

“Harlach,” she said. “Hush. Let me. Okay? This is my job. Let me. Go upstairs with Varney and I’ll bring you something hot to drink and you can lie down and heal. One thing: did you happen to get any idea of the shape and size of the weapon that hurt you?”

He shook his head and then looked miserably dizzy, passing a hand over his face. “No. Didn’t see it at all, just the pain, the blade must have been… hidden somehow, or just too quick—”

“Never mind,” she said. “Go on up to bed. I’ll be up to see you in a bit. Varney?”

Varney nodded and slipped his arm around Harlach’s shoulders with iron strength held in very careful control, taking most of the demon’s weight as they slowly trundled out of the room.

Greta sat back, looking at the detritus of first-aid paraphernalia, and covered her face with her hands. Hadn’t Samael said that the fucking remnant-thing was gone, that the Gladius Sancti were over and done and not going to harm them or anybody else ever again? What was lying in wait for random demons on the course of their normal pursuits and why, other than your standard anti-demon zealot? Those at least were generally too insane to pose any reasonable threat. What the hell was going on, and what did it mean in terms of what she could tell Hildebrandt?

Her phone rang, and after a moment she stripped off her gloves and fished it out of her pocket, staring at the caller ID. Fastitocalon never just called her on the phone. He simply spoke inside her head, courtesy of the mental link they’d shared for most of her life. Why he was suddenly calling her was—

Was maybe as explicable as her amiable surface-op demon acquaintance who took her to work every day being randomly attacked by something that harmed supernaturals.

Fuck.

“Fass?” she said, lifting the phone to her ear. “Tell me you know what the hell I’m supposed to do?”

“Funny you should say that. As a matter of fact,” he said, “I absolutely do.”

“Deeply compassionate and endlessly surprising, this series will steal your heart.” —Grace D. Li, New York Times bestselling author of Portrait of a Thief

In this witty conclusion to a delightful fantasy series finds Greta Helsing, doctor to the undead, facing the latest and strangest challenge of her career…accompanying an anxious angel and a sullen demon on a road trip across America.

After narrowly avoiding the end of the world, the leaders of Heaven and Hell are struggling to collaborate according to the terms of their new treaty—especially because angels and demons are, quite literally, allergic to each other. Seeking a solution, the powers that be decide to see if the allergy persists on Earth by sending an angel and demon on a research trip, first stop: New York City. And what better chaperone than Dr. Greta Helsing, who happens to owe Hell a few favors of her own?

But there’s unrest in New York’s monster underworld and Greta and her team are about to land in the middle of it. Something is off in Heaven and on Earth, and Greta will have to figure out just what that is if she hopes to protect those she loves most.