By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

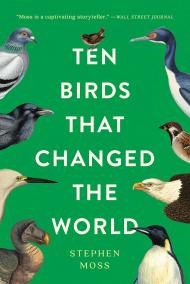

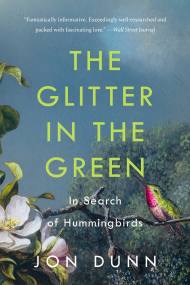

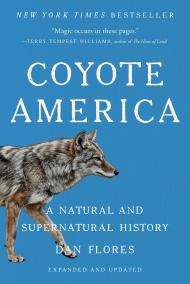

Feathers

The Evolution of a Natural Miracle

Contributors

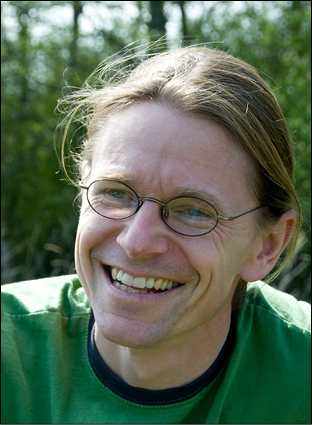

By Thor Hanson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 31, 2011

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465023462

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 31, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Feathers are an evolutionary marvel: aerodynamic, insulating, beguiling. They date back more than 100 million years. Yet their story has never been fully told. In Feathers, biologist Thor Hanson details a sweeping natural history, as feathers have been used to fly, protect, attract, and adorn through time and place. Applying the research of paleontologists, ornithologists, biologists, engineers, and even art historians, Hanson asks: What are feathers? How did they evolve? What do they mean to us?

Engineers call feathers the most efficient insulating material ever discovered, and they are at the root of biology's most enduring debate. They silence the flight of owls and keep penguins dry below the ice. They have decorated queens, jesters, and priests. And they have inked documents from the Constitution to the novels of Jane Austen.

Feathers is a captivating and beautiful exploration of this most enchanting object.

Genre:

-

“[Hanson] has produced a winning book about the extraordinary place of feathers in animal and human history…. like all true birdwatchers, Mr. Hanson knows it isn’t just the bird at the far end of the binoculars but the human being at the near end that matters, and he is writing as much about the human urge to understand, appreciate and appropriate the wild world as he is writing about feathers, which he calls, in his subtitle, a ‘natural miracle.’…. Feathers is an earthbound book, but this does not keep the author—or the reader—from looking up in wonder.”Wall Street Journal

-

“[A] fine book…. Mr. Hanson’s pleasure in feathers is infectious…. [Feathers] is gracious, funny, persuasive and wide ranging. Feathers, Mr. Hanson reminds us, teach a remarkable amount about evolution, insulation, engineering, archaeology and fashion. Better still, as this book shows, they allow not only birds but the human imagination to take flight.”New York Times

-

"An illuminating study of an evolutionary marvel."Economist

-

“Delightful…. [A] fascinating inquiry into one of those common things that are easy to overlook until someone shows what a miracle it is…. Birds, the only animals with feathers today, wear these magic coats of stunning variety whose forms so perfectly fit their functions. Hanson’s book reveals much about that marvelous magic.”Seattle Times

-

“[A] sparkling history…. Well-written science adds gravity to the more featherweight content of witty anecdotes – from interviews with feather-clad Las Vegas showgirls to plucking roadkill in the name of biology. The skillful way Hanson combines the two makes this book popular natural history at its best.”New Scientist

-

"Feathers is an impressive blend of beauty, form, and function."Natural History

-

"Thor Hanson's storytelling is enhanced by his infectious excitement.... Feathers is a compelling introduction to one of nature's wonders"Nature

-

"A readable introduction to feathers and what they mean for birds and mankind."Science

-

"[Hanson] gives unexpected substance to his nearly weightless subject."Discover

-

"Captivating.... Beginning with the evolution of birds, Hanson...unfolds the human fascination with feathers in terms of science, commerce, tools, folklore, art, and aerodynamics with panache."Audubon

-

"There are many feathery gems to be discovered in this book.... Feathers is a book designed to be read, not skimmed, with every page revealing new layers of understanding."Examiner

-

"To read Feathers is to meet up with an enthusiastic old friend who simply cannot wait to tell you about something he just discovered...a must‑read by bird watchers and naturalists of all levels of interest or experience."Bird Watcher's Digest

-

“Enjoyable, wide-ranging, and well-researched…. Highly recommended for birders and science buffs.”Library Journal

-

"A fascinating and eminently readable exploration."Booklist

-

“From basic research about bird biology and the evolutionary origins of feather to falconry, couture, and bioinspiration in industrial design, the book treats us to a series of engaging essays about feathers, both on and off the bird…. Hanson weaves his prior encounters with birds and his experiences as a scientist into the text, offering lively anecdotes about his student days and subsequent life as a professional grant-seeking field biologist. He is particularly adept at portraying how science really works…. Hanson’s prose is polished, lively, and evocative. The outcome is a book that is easy and entertaining to read, yet one that is able to satisfy our intellectual curiosity.… In Feathers, Hanson is remarkably successful at offering something for everyone. Readers from young adults to professional ornithologists and from those interested in nature to those more interested in human culture will enjoy this book…. Ultimately, Feathers is a book to read for pleasure, but along the way, we gain knowledge and insight into nature and our relationship with it.”BioScience

-

“If you feel a sudden need to read about dinosaurs, flyfishing, muttonbirds, and showgirls, this is your book! Absolutely fascinating history, and a terrific read, Feathers is another Thor Hanson classic!”Garth Stein, author of The Art of Racing in the Rain

-

“A fascinating book about the most remarkable—and beautiful—of all avian evolutionary adaptations, with wonderful accounts of ornithological investigations and the solving of biological quandaries and questions, all of it unusually well-written. Highly recommended.”Peter Matthiessen, National Book Award winning author of The Snow Leopard and Shadow Country

-

"This is rich and engaging ornithology at its best."Frank B. Gill, author of Ornithology

-

“Feathers is simply a splendid book! Even for one biased toward butterfly scales, their closest competitors in the animal raiment line, feathers in all their glory can only be seen as astonishing. With elegance and wit, Thor Hanson captures not only their awesome esthetics, but also the astonishing evolution, historical and cultural impact, and sheer wonder of avian plumage. Rendered in exquisite detail with delicate touch, like a feather-painting of old, this is the best kind of natural history—quilled by a real field biologist who is also a fine writer.”Robert Michael Pyle, author of Wintergreen and Mariposa Road

-

“Feathers are truly remarkable. In this book Hanson shows how they are the key to many of the most fascinating and diverse aspects of bird biology, how they have affected our understanding of evolution, and how they have and are enriching our everyday lives. This is science written in clear and entertaining prose; a great read.”Bernd Heinrich, Emeritus Professor of Biology, University of Vermont; author of Winter World and Mind of the Raven