Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

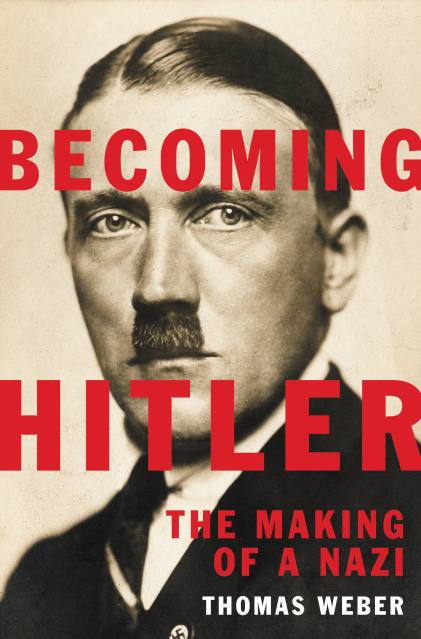

Becoming Hitler

The Making of a Nazi

Contributors

By Thomas Weber

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096626

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $42.00 $54.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Becoming Hitler, award-winning historian Thomas Weber examines Adolf Hitler’s time in Munich between 1918 and 1926, the years when Hitler shed his awkward, feckless persona and transformed himself into a savvy opportunistic political operator who saw himself as Germany’s messiah. The story of Hitler’s transformation is one of a fateful match between man and city. After opportunistically fluctuating between the ideas of the left and the right, Hitler emerged as an astonishingly flexible leader of Munich’s right-wing movement. The tragedy for Germany and the world was that Hitler found himself in Munich; had he not been in Bavaria in the wake of the war and the revolution, his transformation into a National Socialist may never have occurred.

In Becoming Hitler, Weber brilliantly charts this tragic metamorphosis, dramatically expanding our knowledge of how Hitler became a lethal demagogue.