By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

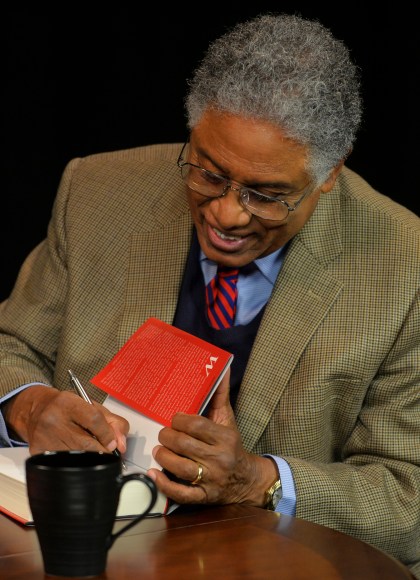

The Thomas Sowell Reader

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 4, 2011

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465022502

Price

$35.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $20.99 $26.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 4, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

These selections from the many writings of Thomas Sowell over a period of a half century cover social, economic, cultural, legal, educational, and political issues. The sources range from Dr. Sowell’s letters, books, newspaper columns, and articles in both scholarly journals and popular magazines. The topics range from late-talking children to “tax cuts for the rich,” baseball, race, war, the role of judges, medical care, and the rhetoric of politicians. These topics are dealt with by sometimes drawing on history, sometimes drawing on economics, and sometimes drawing on a sense of humor.

The Thomas Sowell Reader includes essays on:* Social Issues* Economics* Political Issues* Legal Issues* Race and Ethnicity* Educational Issues* Biographical Sketches* Random Thoughts

“My hope is that this large selection of my writings will reduce the likelihood that readers will misunderstand what I have said on many controversial issues over the years. Whether the reader will agree with all my conclusions is another question entirely. But disagreements can be productive, while misunderstandings seldom are.” — Thomas Sowell

-

"It's a scandal that economist Thomas Sowell has not been awarded the Nobel Prize. No one alive has turned out so many insightful, richly researched books."Steve Forbes

-

"America's best writer on economics, particularly when that discipline intersects with politics."World

-

"Thomas Sowell is, in my opinion, the most interesting philosopher at work in America."Paul Johnson, author of Modern Times