Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

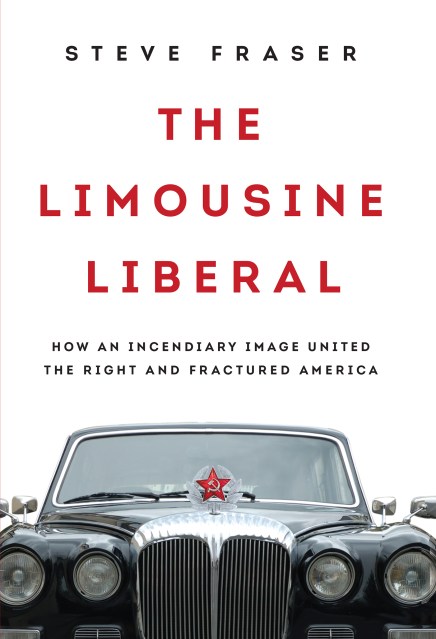

The Limousine Liberal

How an Incendiary Image United the Right and Fractured America

Contributors

By Steve Fraser

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 10, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465097661

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $18.99 $24.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 10, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In The Limousine Liberal, the acclaimed historian Steve Fraser argues that it is impossible to understand American politics without coming to grips with this image, where it originated, why it persists, and where it may be taking us. He reveals that the limousine liberal had existed in all but name long before Procaccino gave it one. From Henry Ford decrying an improbable alliance of Jews, bankers, and Bolsheviks in the 1920s to the Tea Party’s vehement hatred of Hillary Clinton, the fear of the limousine liberal has stoked right-wing populism for nearly a century. Today it fuses together disparate elements of the conservative movement. Sunbelt entrepreneurs on the rise, blue collar ethnics and middle classes in decline, heartland evangelicals, and billionaire business dynasts have found common cause, despite their real differences, in shared opposition to liberal elites.

The Limousine Liberal tells an extraordinary story of why the most privileged and powerful elements of American society were indicted as subversives and reveals the reality that undergirds that myth. It goes to the heart of the great political transformation of the postwar era: the rise of the conservative right and the unmaking of the liberal consensus.