Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

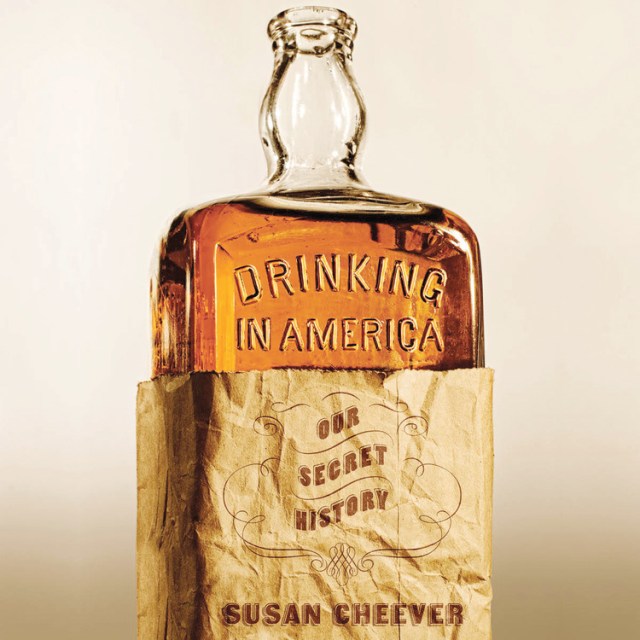

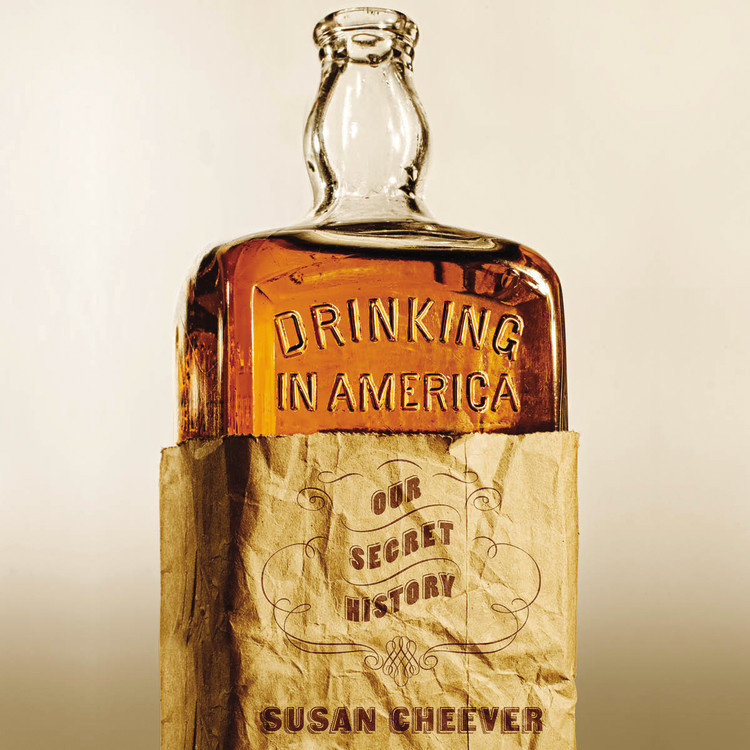

Drinking in America

Our Secret History

Contributors

Read by Barbara Benjamin-Creel

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 13, 2015

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781611135299

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 13, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Drinking in America, bestselling author Susan Cheever chronicles our national love affair with liquor, taking a long, thoughtful look at the way alcohol has changed our nation’s history. This is the often-overlooked story of how alcohol has shaped American events and the American character from the seventeenth to the twentieth century.

Seen through the lens of alcoholism, American history takes on a vibrancy and a tragedy missing from many earlier accounts. From the drunkenness of the Pilgrims to Prohibition hijinks, drinking has always been a cherished American custom: a way to celebrate and a way to grieve and a way to take the edge off. At many pivotal points in our history-the illegal Mayflower landing at Cape Cod, the enslavement of African Americans, the McCarthy witch hunts, and the Kennedy assassination, to name only a few-alcohol has acted as a catalyst.

Some nations drink more than we do, some drink less, but no other nation has been the drunkest in the world as America was in the 1830s only to outlaw drinking entirely a hundred years later. Both a lively history and an unflinching cultural investigation, Drinking in America unveils the volatile ambivalence within one nation’s tumultuous affair with alcohol.

Seen through the lens of alcoholism, American history takes on a vibrancy and a tragedy missing from many earlier accounts. From the drunkenness of the Pilgrims to Prohibition hijinks, drinking has always been a cherished American custom: a way to celebrate and a way to grieve and a way to take the edge off. At many pivotal points in our history-the illegal Mayflower landing at Cape Cod, the enslavement of African Americans, the McCarthy witch hunts, and the Kennedy assassination, to name only a few-alcohol has acted as a catalyst.

Some nations drink more than we do, some drink less, but no other nation has been the drunkest in the world as America was in the 1830s only to outlaw drinking entirely a hundred years later. Both a lively history and an unflinching cultural investigation, Drinking in America unveils the volatile ambivalence within one nation’s tumultuous affair with alcohol.

Genre:

-

"A fascinating look at the place and function of alcohol throughout American history...[Cheever] offers a colorful portrait of a society that, like her own family, has been indelibly shaped by its drinking habits. An intelligently argued study of our country's 'passionate connection to drinking.'"Kirkus Reviews

-

"Susan Cheever offers a humane but unsentimental view of our nation's inebriated past in DRINKING IN AMERICA. To excuse the pun, it's an addictive read full of wit and verve, revealing the deep influence of alcohol on many of our country's most significant moments, from the landing at Plymouth Harbour, to the Kennedy Assassination and Watergate. This is terrific social history but not as it's usually told, and all the better for it."Amanda Foreman, author of Georgiana: Duchess of Devonshire (winner of the Whitbread) and A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War

-

"Cheever's central observation is fascinating...The melting pot, it seems, was also a mixing bowl."Publishers Weekly

-

"Insightful...well-researched and well-developed...An engrossing, in-depth examination of the profound ways alcohol and drinking have shaped and contributed to American history."Shelf Awareness

-

"Cheever is full of such shocking and often delightful revelations of a history we never learned in school."Newsday

-

"I can't stop raving (soberly!) about Susan Cheever's new book... It is both enlightening and frightening. A brilliant and important addition to our understanding of what goes wrong and what can continue to go wrong in a world dominated by the most deadly legal liquid ever invented."Judy Collins

-

"Compelling...[a] brisk drinker's companion to US history, which runs a black light over the archives to ask: who was loaded, and why did it matter?... It's the fourth of Wilson's famous 12 steps that made it common practice for sober folk to dig into their own pasts in order to articulate the role of alcohol - to create a 'searching and fearless moral inventory' - and with DRINKING IN AMERICA, Cheever submits the US to a similar investigation. Along the way, we see a country struggling to negotiate its freedoms, nurtured by alcohol and undone by it as well....This approach can be illuminating, turning those sepia-toned historical figures in wigs into uncertain young men with tankards of rum in their hands."Los Angeles Review of Books

-

"Cheever serves up a sober cocktail of American history...offers up sideways views that are intriguing."Associated Press

-

"Full of compelling ideas...Cheever is smart, perceptive and disciplined...Her Nixon chapter in particular is alternately horrifying and delightful, and paints a compelling picture of the monstrous complexity of a 'great man.'"Buffalo News

-

"Vivid...some of the book's most affecting moments arrive when Cheever discusses her family's drinking problems. "The San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Full of fascinating details...this book is an important and highly entertaining step in the right direction."Women's Voices for Change

-

"Cheever addresses serious subjects with casual and at times humorous prose, making this book surprisingly fun to read. You won't find this booze-filled version of American history in any textbooks, but as with any good barroom conversation, you'll learn just as much."Kansas City Star

-

"A unique cultural tour."BookTrib

-

"Packed with the liquor-soaked legacy of our country...[Cheever] presents a chronicle of the United States that has, to my knowledge, never been attempted. And it is a riveting, revisionist take on so many great events and people...fascinating, unusual history."The Palm Beach Post

-

"Goes down like a smooth glass of wine after a long day...Whether you're a drinker or a teetotaler, if you like a wee nip of history, then here's the book you want."The Bookworm Sez

-

"A highly readable, in-your-face look at not only the destructive power of alcohol in America, but the strange way it shaped our history."San Antonio Express-News

-

"If you're looking for a sobering introduction to drunk history, this is the book for you."Toronto Star

-

"At once fascinating and slightly disturbing."The Oklahoman

-

"DRINKING IN AMERICA at times has many shocking revelations of the role alcohol has played in our country that is a great addition to the legends of this nation."Midwest Book Review

-

"This is Drunk History, but thoroughly researched and soberly elucidated."The Portland Mercury

-

"Cheever lays bare something many of us know intimately: 'alcoholism is a family disease,' she writes, and its roots in the American family run deep."Boston Globe

-

"[A] cockeyed retelling of the American story."The Week

-

"A riveting, revisionist take on so many great events and people... fascinating, unusual history... her research is spot on."The New York Social Diary

-

"A chronicle of America's past that is full of details they never told you back in fifth grade."Minneapolis Star Tribune

-

"Informative, entertaining and scary...this book brings history to life and pours it a tall one."High Times