Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

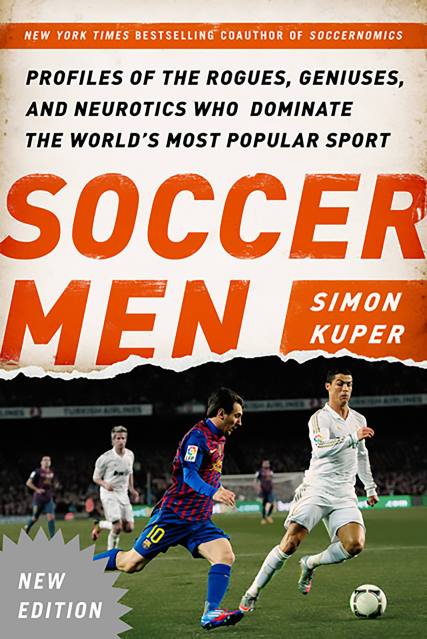

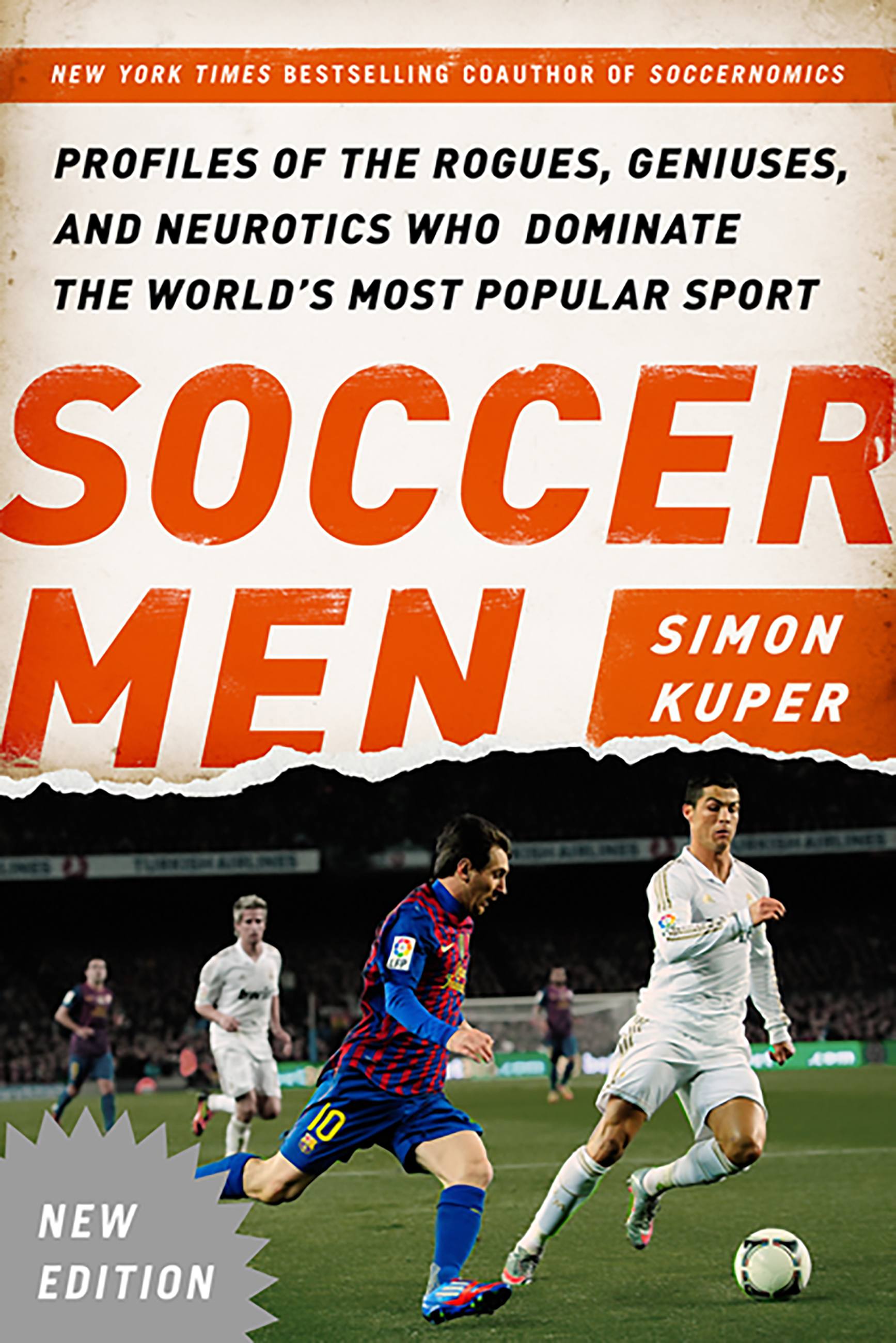

Soccer Men

Profiles of the Rogues, Geniuses, and Neurotics Who Dominate the World's Most Popular Sport

Contributors

By Simon Kuper

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 22, 2014

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568584584

Price

$16.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $19.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 22, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Soccer Men goes behind the scenes with soccer’s greatest players and coaches. Inquiring into the genius and hubris of the modern game, Kuper details the lives of giants such as Arsè Wenger, Jose Mourinho, Jorge Valdano, Lionel Messi, Kakáand Didier Drogba, describing their upbringings, the soccer cultures they grew up in, the way they play, and the baggage they bring to their relationships at work.

From one of the great sportswriters of our time, Soccer Men is a penetrating and surprising anatomy of the figures that define modern soccer.