Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

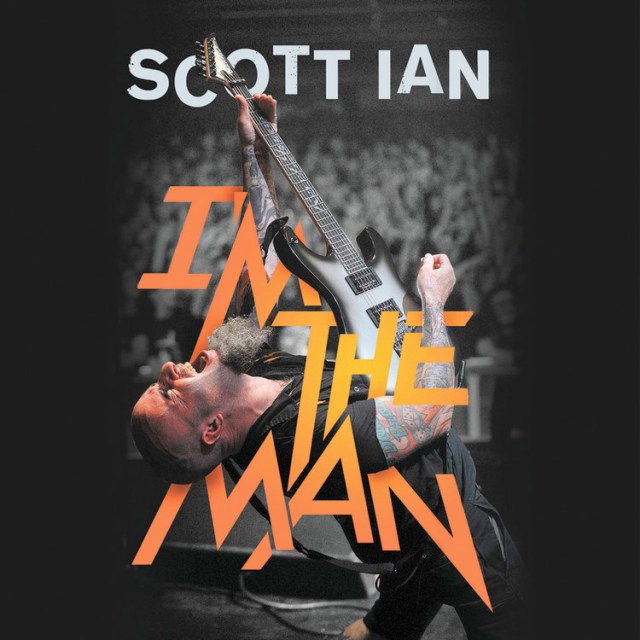

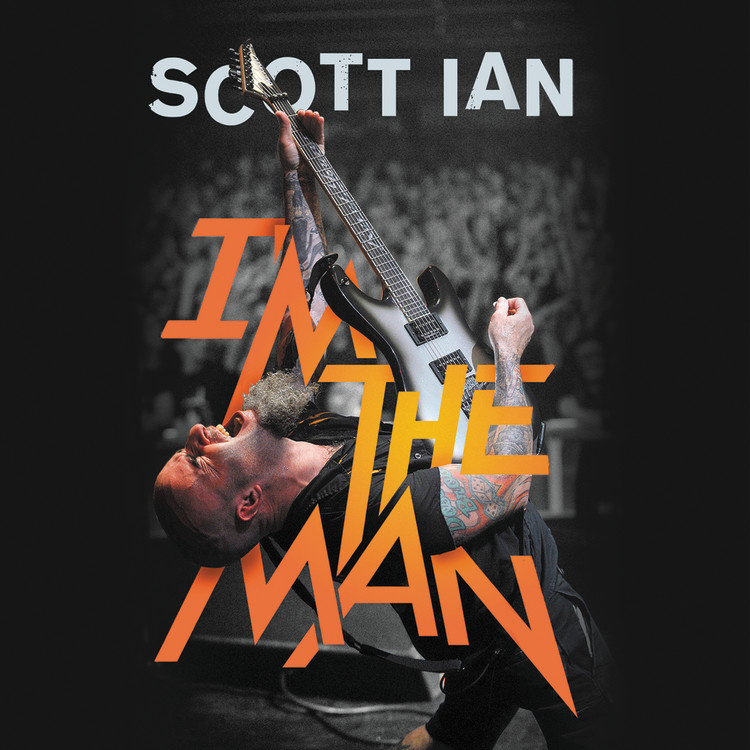

I’m the Man

The Story of That Guy from Anthrax

Contributors

By Scott Ian

With Jon Wiederhorn

Foreword by Kirk Hammett

Read by Scott Ian

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 25, 2017

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478944621

Format

Format:

Audiobook Download (Unabridged)This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 25, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

I'm the Man is the fast-paced, humorous, and revealing memoir from the man who co-founded Anthrax, the band that proved to the masses that brutality and fun didn't have to be mutually exclusive. Through various lineup shifts, label snafus, rock 'n' roll mayhem, and unforeseen circumstances galore, Scott Ian has approached life and music with a smile, viewing the band with deadly seriousness while recognizing the ridiculousness of the entertainment industry. Always performing with abundant energy that revealed his passion for his craft, Ian has never let the gravity of being a rock star go to his shaven, goateed head.

Ian tells his life story with a clear-eyed honesty that spares no one, least of all himself, starting with his upbringing as a nerdy Jewish boy in Queens and evolving through his first musical epiphany when he saw KISS live on television and realized what he wanted to do with his life. He chronicles his adolescence growing up in a dysfunctional home where the records blasting on his stereo failed to drown out the sound of his parents shouting at one another. He sets down the details of his fateful escape into the turbulent world of heavy metal. And of course he lays bare the complete history of Anthrax — from the band's formation to their present-day reinvigoration — as they wrote and recorded thrash classics like Spreading the Disease, Among the Living, and the top-twenty-charting State of Euphoria.

Along the way, Ian recounts harrowing, hysterical tales from his long tour of duty in the world of hard rock. He witnesses the rise of Metallica, for which he had a front row seat. He parties with the late Dimebag Darrell while touring with Pantera and gets wild with Black Label Society frontman and longtime Ozzy Osbourne guitarist Zakk Wylde. He escapes detection while interviewing Ozzy for "The Rock Show" while dressed as Gene Simmons and avoids arrest after getting detained on suspicion of drugs while riding the tube in England with the late Metallica bassist Cliff Burton.

In addition, I'm the Man addresses the trials and tribulations of Ian's life and loves. He admits his foibles and reveals the mistakes made along the way to becoming a fully-functioning adult. He celebrates finally finding peace and a true sense of family with his wife, singer/songwriter Pearl Aday, and examines how his world changed after the birth of their first son.

I'm the Man is a blistering hard rock memoir, one that is astonishing in its candor and deftly told by the man who's kept the institution of Anthrax alive for more than thirty years.

-

Jabby, gabby, and metal-obsessed...exhilarating.New York Times

-

Scott writes with real honesty...I'm the Man stands up as a great insight into one of metal's leading figures. And you don't have to be a thrash or rock fan to enjoy itJewish Telegraph

-

Eye-opening...The hard-charging head-banger has assembled his best anecdotes into the revealing autobiography...For every familiar factoid, Ian introduces two or three new nuggets even diehard Anthrax fans probably don't know...Despite the shenanigans and chicanery of Ian's teens and twenties, the man who emerges here is surprisingly level-headed and articulate.Cleveland Music Examiner.com