Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

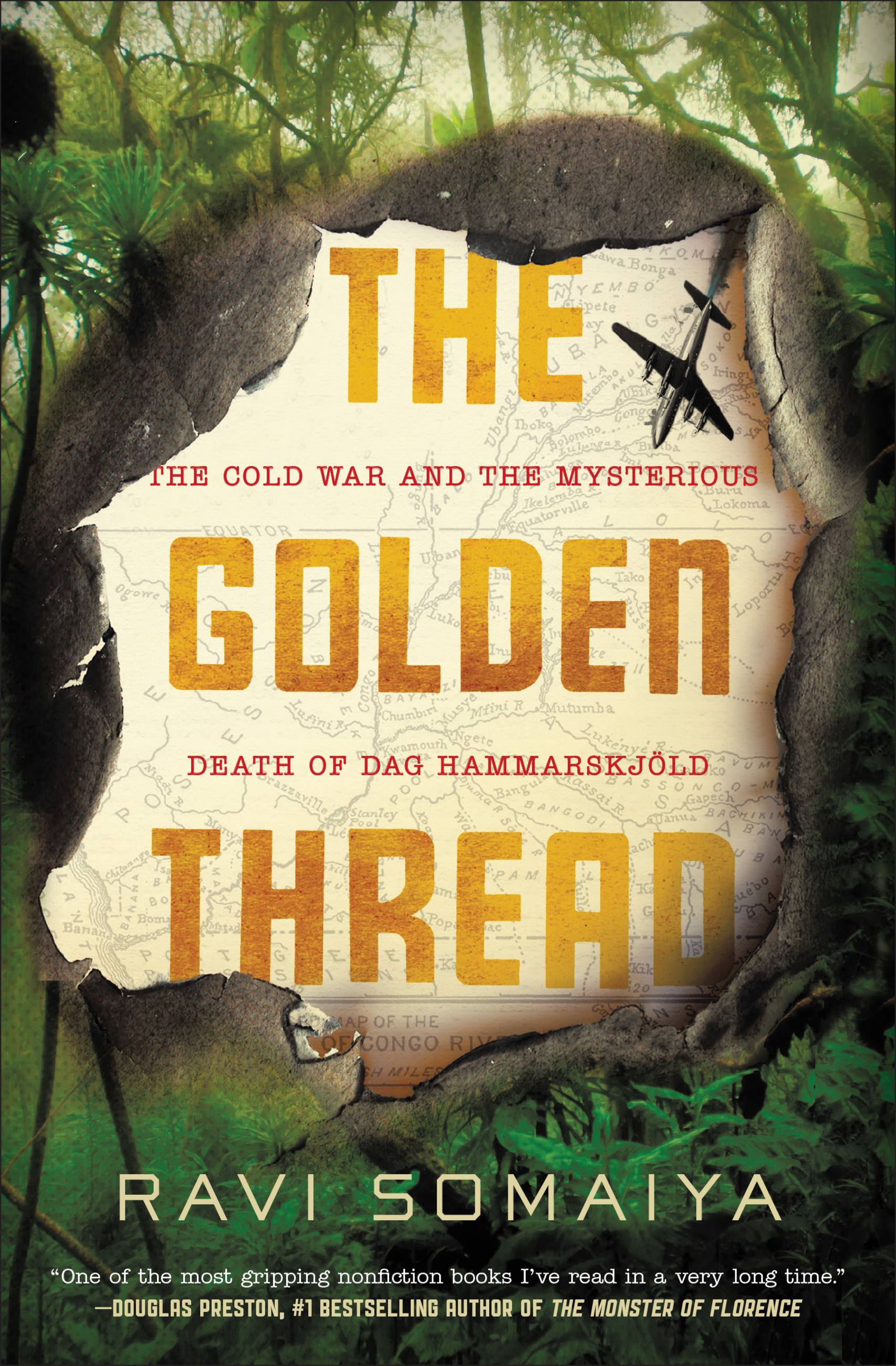

The Golden Thread

The Cold War and the Mysterious Death of Dag Hammarskjöld

Contributors

By Ravi Somaiya

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 7, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455536535

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 7, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

LONGLISTED FOR THE ALCS "GOLD DAGGER" AWARD FOR NON-FICTION CRIME WRITING

Uncover the story behind the death of renowned diplomat and UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld in this true story of spies and intrigue surrounding one of the most enduring unsolved mysteries of the twentieth century.

Uncover the story behind the death of renowned diplomat and UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld in this true story of spies and intrigue surrounding one of the most enduring unsolved mysteries of the twentieth century.

On September 17, 1961, Dag Hammarskjöld boarded a Douglas DC6 propeller plane on the sweltering tarmac of the airport in Leopoldville, the capital of the Congo. Hours later, he would be found dead in an African jungle with an ace of spades playing card placed on his body.

Hammarskjöld had been the head of the United Nations for nine years. He was legendary for his dedication to peace on earth. But dark forces circled him: Powerful and connected groups from an array of nations and organizations—including the CIA, the KGB, underground militant groups, business tycoons, and others—were determined to see Hammarskjöld fail.

A riveting work of investigative journalism based on never-before-seen evidence, recently revealed firsthand accounts, and groundbreaking new interviews, The Golden Thread reveals the truth behind one of the great murder mysteries of the Cold War.

Genre:

-

"THE GOLDEN THREAD is as exciting as the best spy novels, with the enormous advantage of being completely true. Ravi Somaiya masterfully teases out the tangled strands of a Cold War mystery in a place where nothing and no one are quite what they seem. The result is a gripping book by a gifted writer and a dogged investigator."Mitchell Zuckoff, #1 New York Times bestselling author of 13 Hours and Fall and Rise: The Story of 9/11

-

"THE GOLDEN THREAD is one of the most gripping nonfiction books I've read in a very long time, a real-life thriller about the mysterious death of Dag Hammarskjold, the second Secretary General of the UN, in 1961. Somaiya is one of the country's best journalists, and he's used his prodigious reporting and researching skills to dig up some truly startling new information about the plane crash in the Congo that killed Hammarskjold and spawned an almost never-ending series of conspiracy theories. Somaiya does a masterful job sifting the evidence and building a case of murder. This is a fabulous page turner. I highly recommend it."Douglas Preston, #1 bestselling author of The Monster of Florence

-

"Ravi Somaiya's brilliant unwrapping of the mystery surrounding Hammarskjold's death will convert the reader into an avid investigator the moment they pick up this book! A compelling read -- filled with revelations and written in a style that's clean and fast-paced, THE GOLDEN THREAD also raises key questions before governments who still act suspiciously: Why? What are you hiding exactly? At its heart, the book lays bare not only Hammarskjold's undoubted heroism and the sad realities of the Congo in the 1960s (many features of which regrettably persist to this day), but also the stark dilemmas that beset the UN, when principle falls neatly into the cross-hairs of power."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 3.0px 0.0px; line-height: 27.0px; font: 12.0px Arial; color: #181817; -webkit-text-stroke: #181817; background-color: #ffffff}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, UN Human Rights Chief (2014-2018) and UN peacekeeper (1994-1996)

-

"[An] impressive debut...This is an eye-opening account that could lead to renewed public interest in this tragedy."Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

-

"Verdict: Fans of novelists such as Tom Clancy and Robert Ludlum, as well as military history and true crime enthusiasts, will find much to enjoy about this riveting read."Library Journal

-

"[A] gripping account of Hammarskjöld's death and the ensuing search for the truth about what happened to him."InsideHook

-

"One of the mysteries I've long been fascinated by, and am so grateful that Ravi Somaiya has cracked it open so brilliantly."David Grann