By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

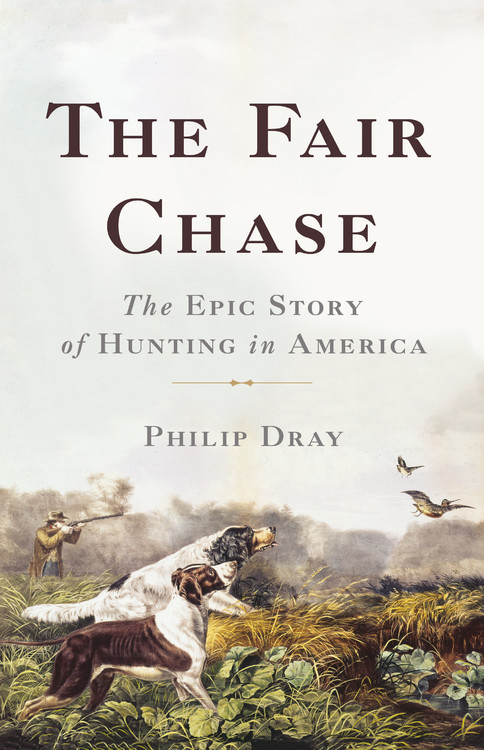

The Fair Chase

The Epic Story of Hunting in America

Contributors

By Philip Dray

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 1, 2018

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465061723

Price

$35.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From Daniel Boone to Teddy Roosevelt, hunting is one of America’s most sacred-but also most fraught-traditions. It was promoted in the 19th century as a way to reconnect “soft” urban Americans with nature and to the legacy of the country’s pathfinding heroes. Fair chase, a hunting code of ethics emphasizing fairness, rugged independence, and restraint towards wildlife, emerged as a worldview and gave birth to the conservation movement. But the sport’s popularity also caused class, ethnic, and racial divisions, and stirred debate about the treatment of Native Americans and the role of hunting in preparing young men for war.

This sweeping and balanced book offers a definitive account of hunting in America. It is essential reading for anyone interested in the evolution of our nation’s foundational myths.

Genre:

-

"How hunting came to hold an iconic place in American culture in the first place is an interesting tale, and in The Fair Chase Philip Dray explores it with a balance and fair-mindedness that is unusual for such a contentious subject...The great strength of this telling is the author's ability to see that little about his story is black and white."Wall Street Journal

-

"Lively and compelling...A capacious and erudite history of the practice and meanings of hunting in American life...Written with sensitivity and bracketed with judgement, it describes a culture and asks questions, telling a story full of paradoxes and nuance...As an unrivaled history, and an admirably crafted bid to deepen dialogue between groups of Americans who might otherwise view one another as alien or out of touch, Dray's Fair Chase is a vital intervention."New Republic

-

"Enlightening...The Fair Chase isn't a book about ethics and philosophy, but Dray does a fine job introducing his readers to the issues at play...He isn't afraid to lay out hard truths."New York Times Book Review

-

"An eloquent, thoughtful, and nuanced cultural history of American hunting."Choice

-

"A fluid and fascinating history for hunters and nonhunters alike."Garden & Gun

-

"Revealing...[Dray] does a marvelous job walking us, mostly chronologically, through nearly every aspect and controversy of hunting's long history, with themes of ethics ('fair chase, the idea that hunted animals must have a chance to evade or flee their pursuers') and conservation looming large throughout...A lively history that can be enjoyed by hunters and conservationists alike."Kirkus

-

"In this well-written, wide ranging history that is at once literary and infused with a passion for wild things, Philip Dray reveals how American sportsmen have continually remade hunting in ways that both expressed and contributed to broader shifts in the nation's culture. An essential book for anyone who wants to understand the origins of our ongoing debates about hunting and wildlife."Louis Warren, author of Buffalo Bill's America

-

"The Fair Chase is a comprehensive and delightful account of the mystique of sport hunting and firearms in our history. Philip Dray has given us a deeply researched epic story of hunting and the literary tradition that celebrates wilderness, the chase, iconic figures such as Daniel Boone and Sitting Bull, the hunter's code of ethics, the western in print and film, and the continuing romance of firearms, along with animal rights, and meditation on the future of hunting. This is history writing at its exciting best."Robert Morgan, author of Lions of the West

-

"Less than ten percent of the population now hunts, but they still represent a large symbolic place in our national narrative. Philip Dray helps us understand why hunting and hunters continue to shape our ongoing debates about our relationship to wildlife, endangered species, and environmental policy. Given the dramatic changes in the management ethos of our natural resources brought on by the Trump administration, The Fair Chase is a timely and engaging reminder of what's at stake."Jan E. Dizard, author of Going Wild and Mortal Stakes

-

"In The Fair Chase, Philip Dray tells the story, by turns appalling and inspiring, of hunting in the U.S. and how successive waves of media imagery transformed it from simple meat procurement into a recreational activity embodying shifting beliefs about the land and its European conquerors, animals and humans, and humanity and nature. No matter how you feel about hunters and hunting, this book will fascinate you and make you rethink your ideas."Matt Cartmill, author of A View to a Death in the Morning

-

"In The Fair Chase, Philip Dray expertly guides his readers through one of the great American stories. Hunters and non-hunters alike will appreciate how Dray uses the chase to illuminate the central tensions and dilemmas of the American relationship with the natural world."Karl Jacoby, author of Crimes Against Nature

-

"It is still a matter of debate as to how much hunting is in our DNA as individuals. As a nation, on the other hand, hunting is a basic building block, essential to our national story. Philip Dray traces the origins of our founding relationship with guns to today, when, while fewer people hunt, hunting and the politics it aligns with holds tremendous sway. Surveying huge tracts of history swiftly and concisely, Dray makes the largely overlooked point that for all the complicated emotions it incites, hunting may hold some answers to ways we might universally reconnect with a natural world that we are racing to destroy."Robert Sullivan, author of Rats