By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

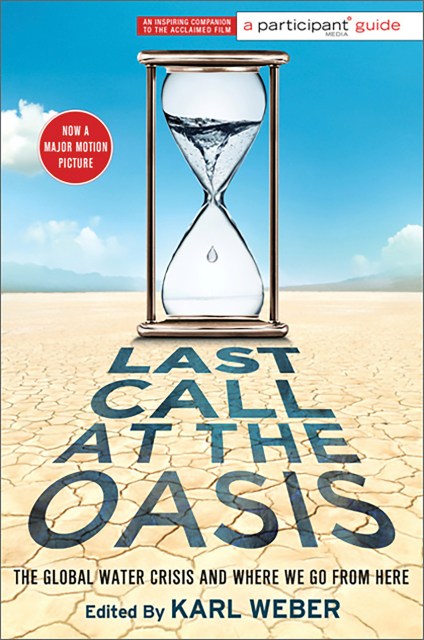

Last Call at the Oasis

The Global Water Crisis and Where We Go from Here

Contributors

By Participant

Edited by Karl Weber

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2012

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586489786

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Less than 1 percent of the world’s water is fresh and potable — and no more will ever be available. Thanks to pollution, global warming, and population growth, water access is poised to become today’s most explosive global issue. This book, based on the film Last Call at the Oasis by Academy Award-winning director Jessica Yu, offers insights into the coming water crisis from visionary scientists, policymakers, activists, and environmentalists, including:

- ROBERT MORAN on how oil and mineral development pollute and divert water supplies — often beyond public scrutiny

- PETER H. GLEICK on discovering the “soft path” to global water security

- ROBERT GLENNON on how the power of markets can help protect the world’s water

- LYNN HENNING on how a family farmer became a passionate “water activist”

- ALEX PRUD’HOMME on how the water crisis affects us all

- GARY WHITE on how innovative social and economic strategies can make clean water available even for the world’s poorest people

- HADLEY ARNOLD AND PETER ARNOLD on how arid regions like America’s Southwest can wisely husband water supplies for cities and farmers alike

- ROBYN BEAVERS on how today’s smartest businesses are making sustainable water management a competitive advantage

- ZEM JOAQUIN on nine “ecofabulous” ways of saving water at home — and doing it with style

- BILL MCDONOUGH on how smart design can preserve water’s “Endless Resourcefulness” for generations to come

No resource on earth is more precious — or more endangered — than water. Last Call at the Oasis is a powerful tool for learning about the water challenges we face as well as the remarkable solutions available to us — if we have the will to use them.

Genre:

-

Midwest Book Review

“With concern mixed in with optimism for a better solution, “Last Call at the Oasis” is a strong pick for environmental issues and studies collection and for readers who want to understand the importance of water in coming years.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use