By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

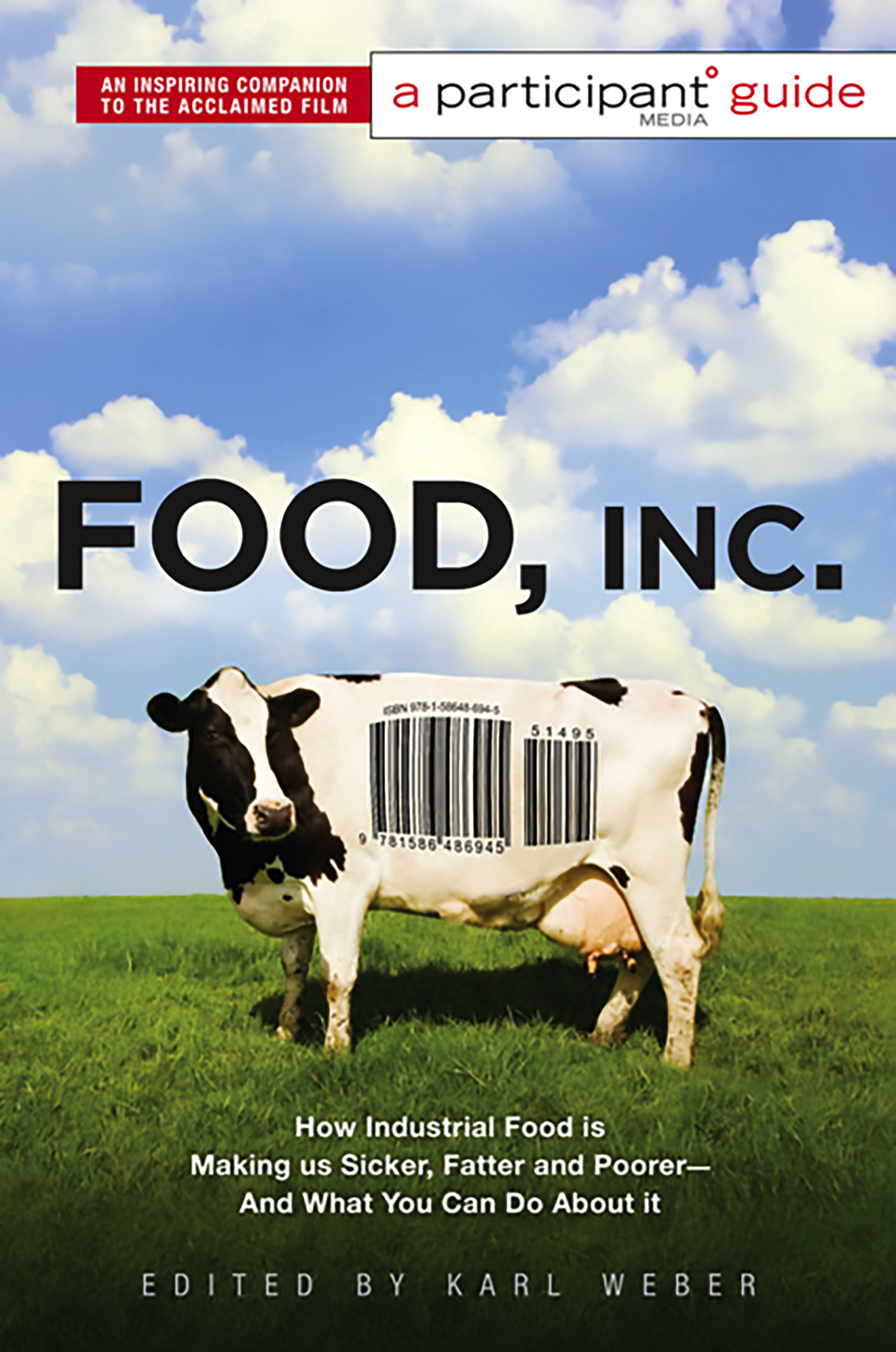

Food, Inc.: A Participant Guide

How Industrial Food is Making Us Sicker, Fatter, and Poorer-And What You Can Do About It

Contributors

Edited by Participant

Edited by Karl Weber

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 5, 2009

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586486945

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Media Tie-In) $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook (Media Tie-In) $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Expanding on the film’s themes, the book Food, Inc. will answer those questions through a series of challenging essays by leading experts and thinkers. This book will encourage those inspired by the film to learn more about the issues, and act to change the world.

Genre:

-

David Denby, New Yorker

“Those of us who avoid junk food, with many sighs of relief and self-approval, may still be eating junk a good deal of the time. This enraging fact, which will not surprise anyone who has read such muckraking books as Eric Schlosser’s “Fast Food Nation” (2001) and Michael Pollan’s “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” (2006), is one of the discomforting meanings of the powerful new documentary “Food, Inc.,” an angry blast of disgust aimed at the American food industry.”

The American Conservative

“If you care about what you’re eating, you should see the new documentary Food Inc.”

Takepart.com

“Most of you have probably heard about Food, Inc., the movie, but did you also know there’s a companion book to the film? The book explores the challenges raised by the movie in fascinating depth through 13 essays, most of them written especially for this book, and many by experts featured in the film. Highlights include chapters by Michael Pollan (Omnivore’s Dilemma and In Defense of Food), Anna Lappe (Hope’s Edge and Grub), Eric Schlosser (Fast Food Nation and film co-producer), Robert Kenner (film director), and a chapter on asking the right questions from Sustainable Table! The book is so popular it’s already in its fourth printing.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use