By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

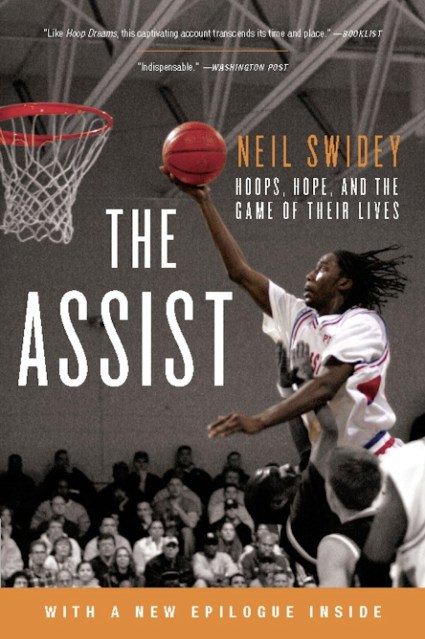

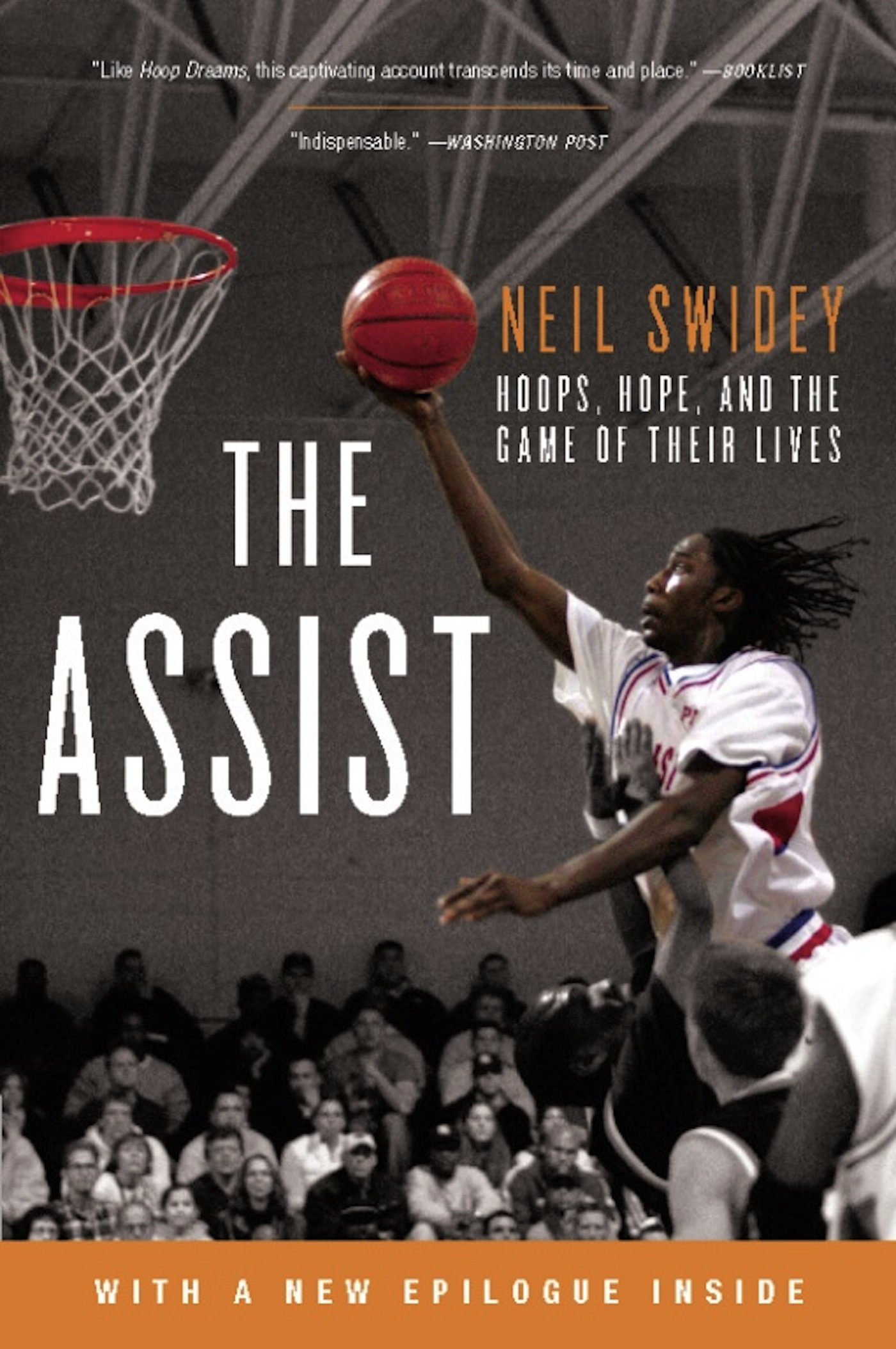

The Assist

Hoops, Hope, and the Game of Their Lives

Contributors

By Neil Swidey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 11, 2008

- Page Count

- 392 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786727025

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 11, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Revolving around fascinating, complex characters, The Assist is a captivating narrative of a basketball team in pursuit of a championship that also drills down into the legacy of desegregation and explores issues of education, family, and race. O’Brien is a middle-aged white guy coaching an all-black team playing in an all-white neighborhood that three decades ago was at the center of the busing wars dividing cities across the country — a time and place indelibly described in J. Anthony Lukas’s powerful book Common Ground. It’s the inspiring story of a man who makes a difference, and of boys surmounting nearly impossible odds; it is also the story of the ones who don’t make it, and why.

-

A Washington Post Best Book of 2008 Selection

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use