Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

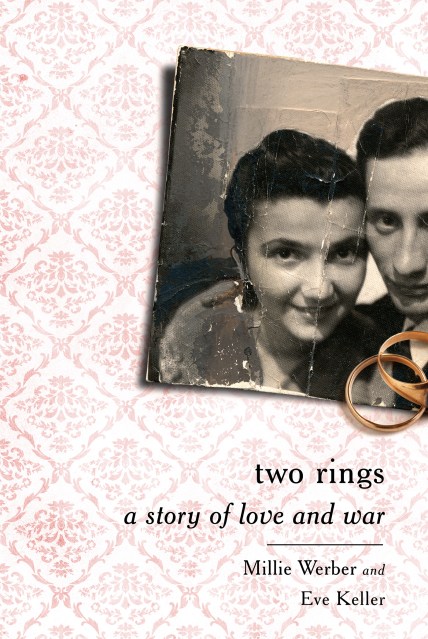

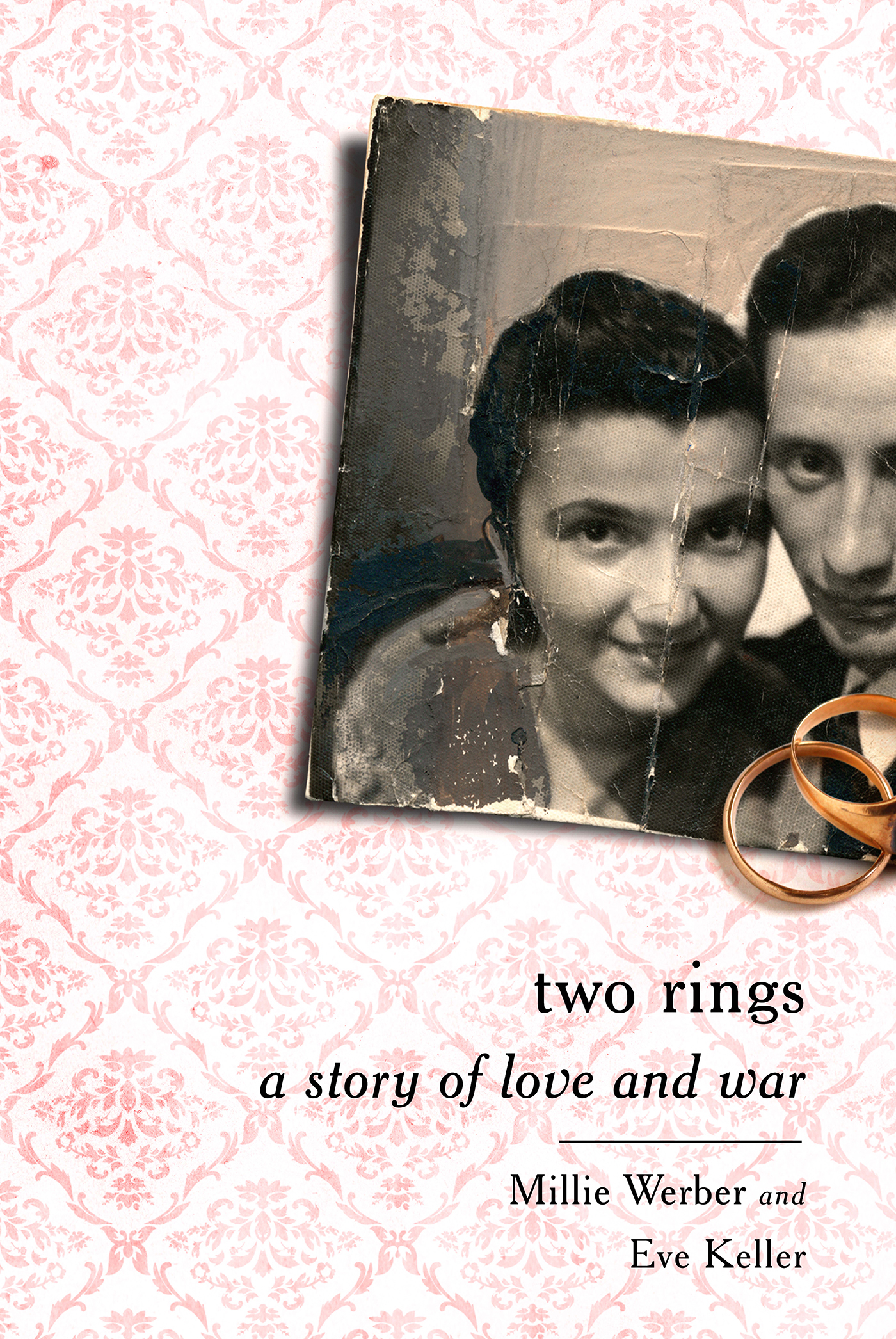

Two Rings

A Story of Love and War

Contributors

By Eve Keller

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 27, 2012

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391238

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 27, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Judged only as a World War Two survivor’s chronicle, Millie Werber’s story would be remarkable enough. Born in central Poland in the town of Radom, she found herself trapped in the ghetto at the age of fourteen, a slave laborer in an armaments factory in the summer of 1942, transported to Auschwitz in the summer of 1944, before being marched to a second armaments factory. She faced death many times; indeed she was certain that she would not survive. But she did.

Many years later, when she began to share her past with Eve Keller, the two women rediscovered the world of the teenage girl Millie had been during the war. Most important, Millie revealed her most precious private memory: of a man to whom she was married for a few brief months. He was — if not the love of her life — her first great unconditional passion. He died, leaving Millie with a single photograph taken on their wedding day, and two rings of gold that affirm the presence of a great passion in the bleakest imaginable time.