By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

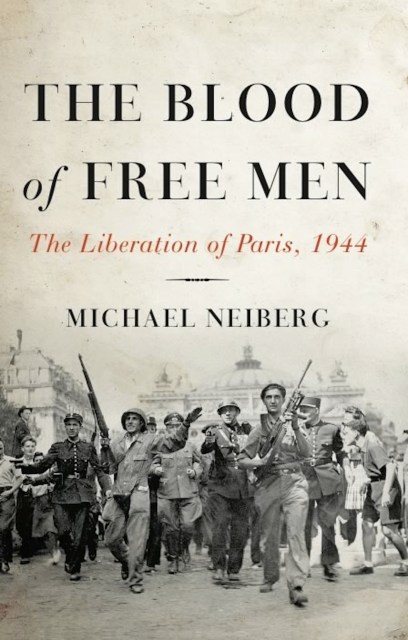

The Blood of Free Men

The Liberation of Paris, 1944

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 2, 2012

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465033034

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 2, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In The Blood of Free Men, celebrated historian Michael Neiberg deftly tracks the forces vying for Paris, providing a revealing new look at the city’s dramatic and triumphant resistance against the Nazis. The salvation of Paris was not a foregone conclusion, Neiberg shows, and the liberation was a chaotic operation that could have easily ended in the city’s ruin. The Allies were intent on bypassing Paris so as to strike the heart of the Third Reich in Germany, and the French themselves were deeply divided; feuding political cells fought for control of the Resistance within Paris, as did Charles de Gaulle and his Free French Forces outside the city. Although many of Paris’s citizens initially chose a tenuous stability over outright resistance to the German occupation, they were forced to act when the approaching fighting pushed the city to the brink of starvation. In a desperate bid to save their city, ordinary Parisians took to the streets, and through a combination of valiant fighting, shrewd diplomacy, and last-minute aid from the Allies, managed to save the City of Lights.

A groundbreaking, arresting narrative of the liberation, The Blood of Free Men tells the full story of one of the war’s defining moments, when a tortured city and its inhabitants narrowly survived the deadliest conflict in human history.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use