Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

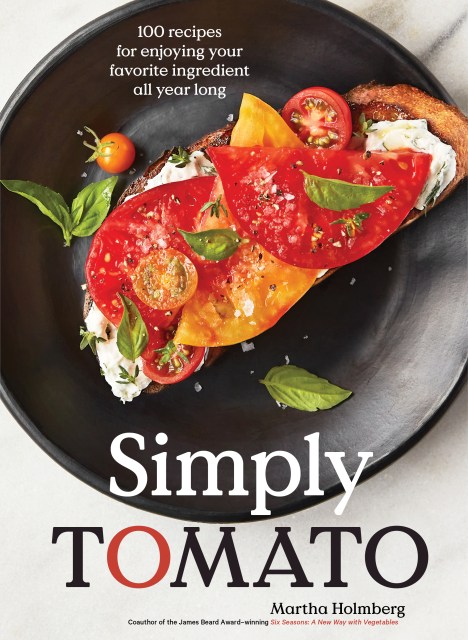

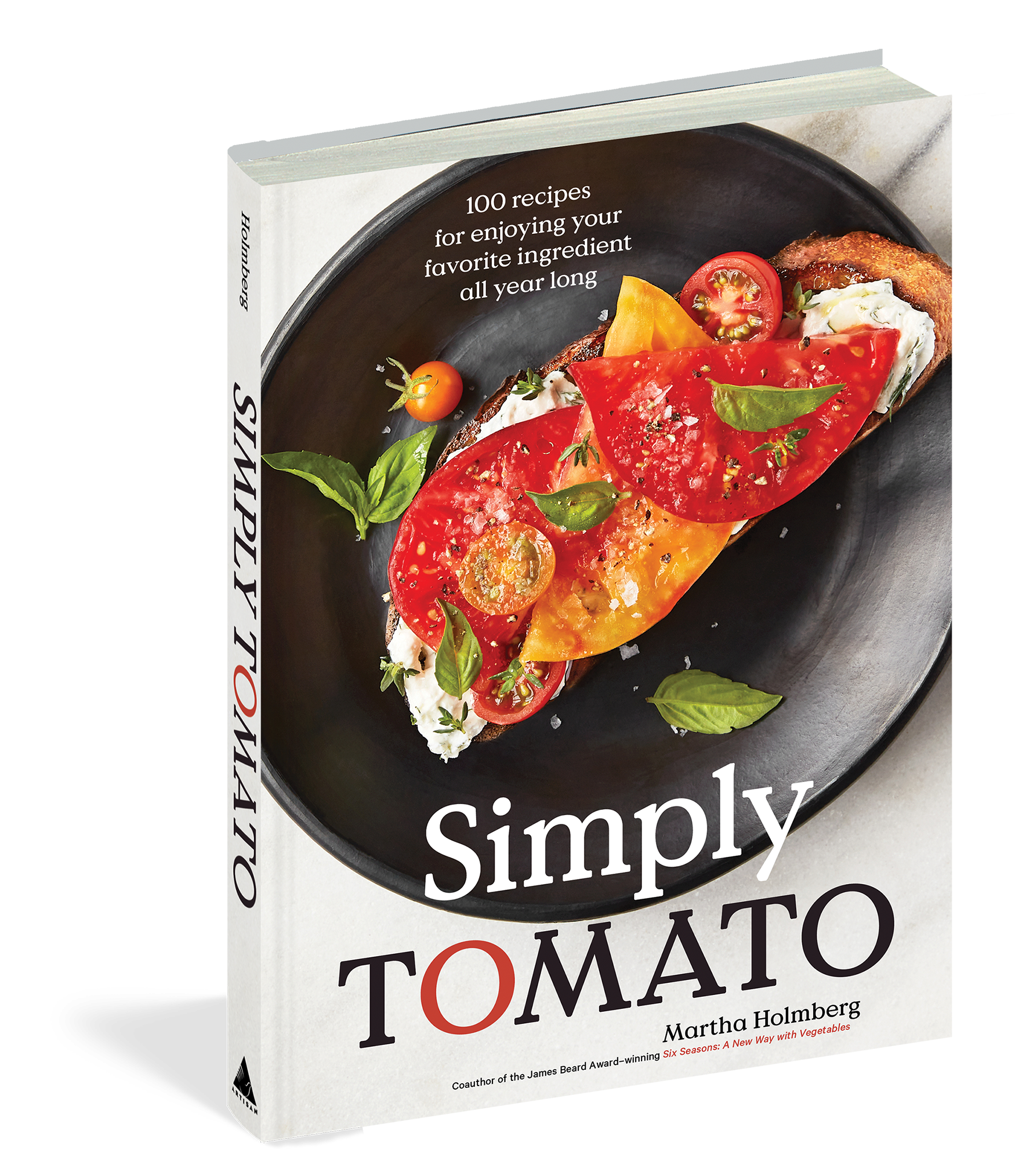

Simply Tomato

100 Recipes for Enjoying Your Favorite Ingredient All Year Long

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 20, 2023

- Page Count

- 248 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781648290374

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 20, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

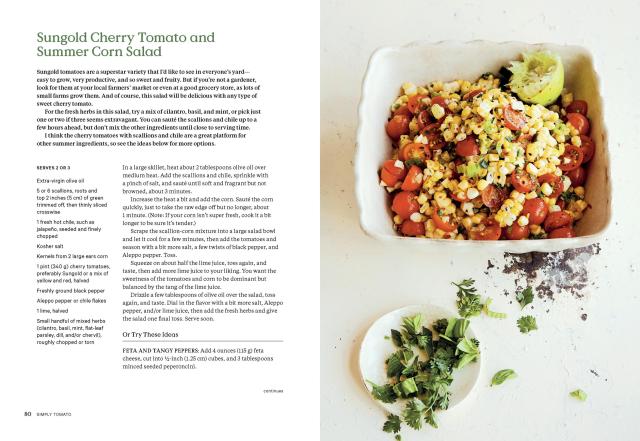

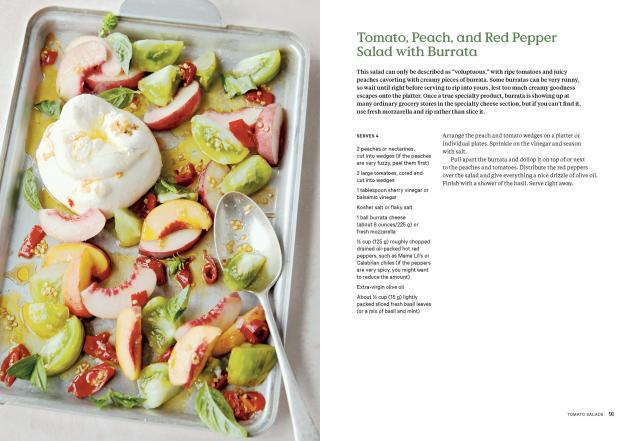

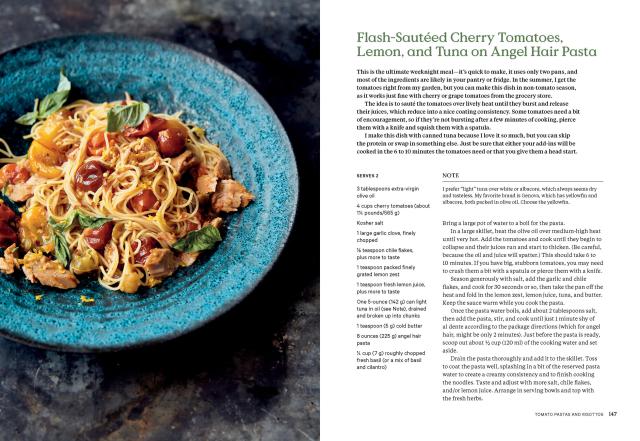

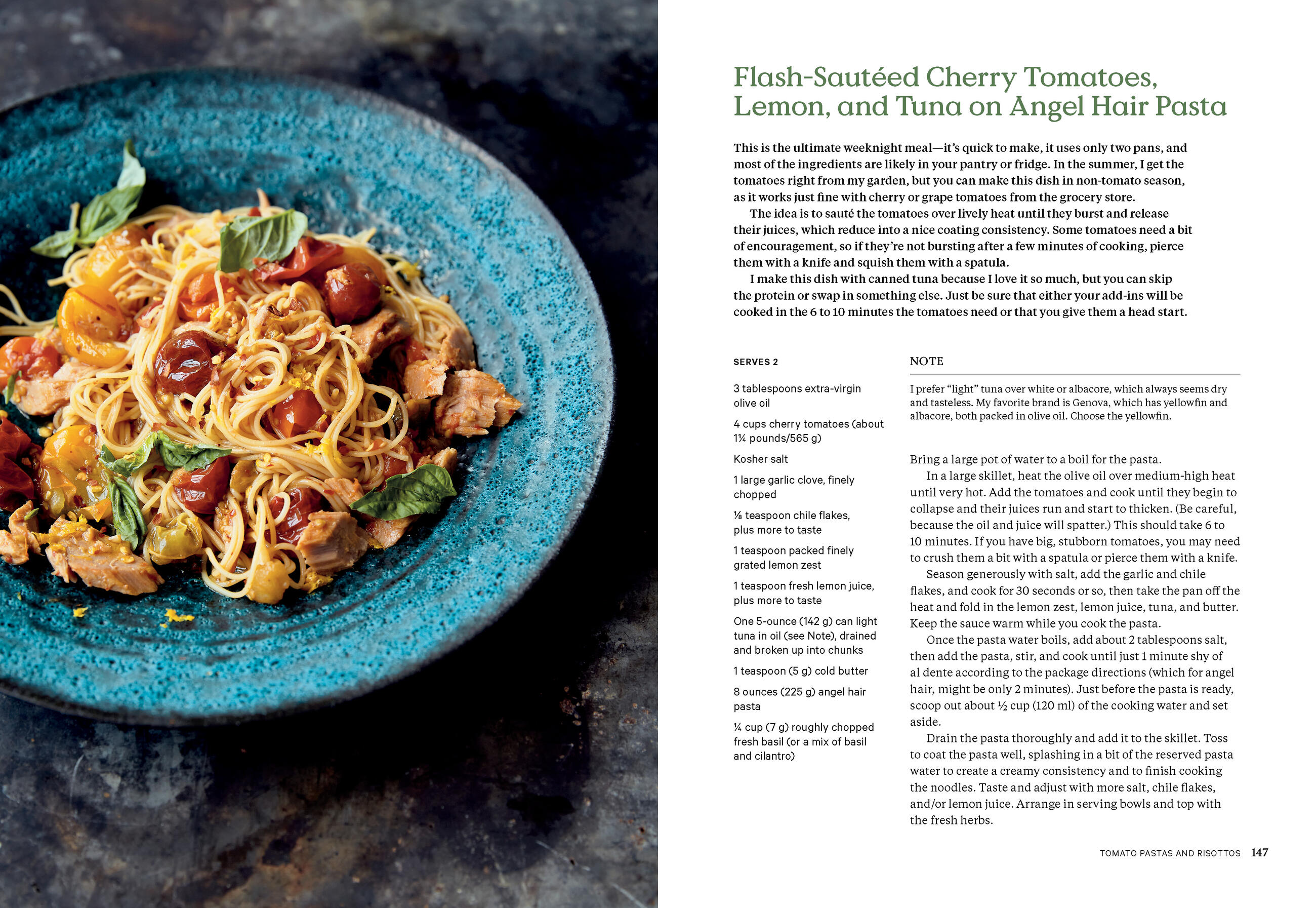

Americans eat more tomatoes than any vegetable except for the potato. But what do we do with all those tomatoes? Acclaimed chef, cooking teacher, and author Martha Holmberg shares 100 recipes to turn the tomato into glorious dishes. Whether it’s a fresh-off-the-vine tomato or a just-picked-from-the-supermarket-shelf tomato, Holmberg has ideas to make the best of our favorite summer fruit. There are three versions of gazpacho, five ways to top roasted tomato puff pastry, plus Tomato and Zucchini Gratin, Classic Panzanella, Tomato Risotto, and Stuffed Tomatoes with Spiced Beef Piccadillo. With more tomato varieties in existence than ever before, Holmberg explains which tomatoes work best with which recipes: choose a beefsteak to roast with fish or pick cherry tomatoes to toss with corn in a quick summer salad. Holmberg also reveals her secret, umami-packed ingredient—tomato water. She calls it a “magical elixir” that can add intense tomato flavor to most anything you make.

-

“James Beard Award winner Holmberg informs and delights. . . . An indispensable resource.”Publishers Weekly, STARRED REVIEW

-

“Consider this the tomato Bible. . . . The 100 dishes will turn tomato cooking/eating habits upside down. . . . Destined to be an all-season favorite.”Booklist, STARRED REVIEW

-

“Whether they’re straight off the vine or from the grocery store, [Holmberg] shares no-fuss steps for making a variety of easy tomato meals packed with glorious flavor and zest. . . . Sure to bring joy to your kitchen!”First for Women

-

“This book is as delightful as its subject matter (if not more so!). I did not know I could love tomatoes more until Martha showed me how. She perfectly masters transforming a simple ingredient into the unexpected in this delightful and whimsical book.”Justine Doiron of @Justine_Snacks

-

“Martha teaches us how to pick the perfect tomatoes and turn them into dishes you’ll be dying to eat—soups and salads, of course, but also hand pies, gratins, tarts, and more.”Joshua McFadden, author of Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables and Grains for Every Season

-

“If, like Martha, you get ‘a ripple of joy when you hold a ripe tomato,’ then you’ll get a tidal wave of glee when you cook from this book. Whether it’s the Upgraded Niçoise Salad with Roasted Tomatoes and Deviled Eggs or the Seafood and Tomato Soup, there’s a surprise in each recipe and so much delight in the collection. You don’t have to have a tomato patch to cook the recipes, but their allure just might make you want to dig up some dirt and start a garden.”Dorie Greenspan, New York Times bestselling author of Baking with Dorie