Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

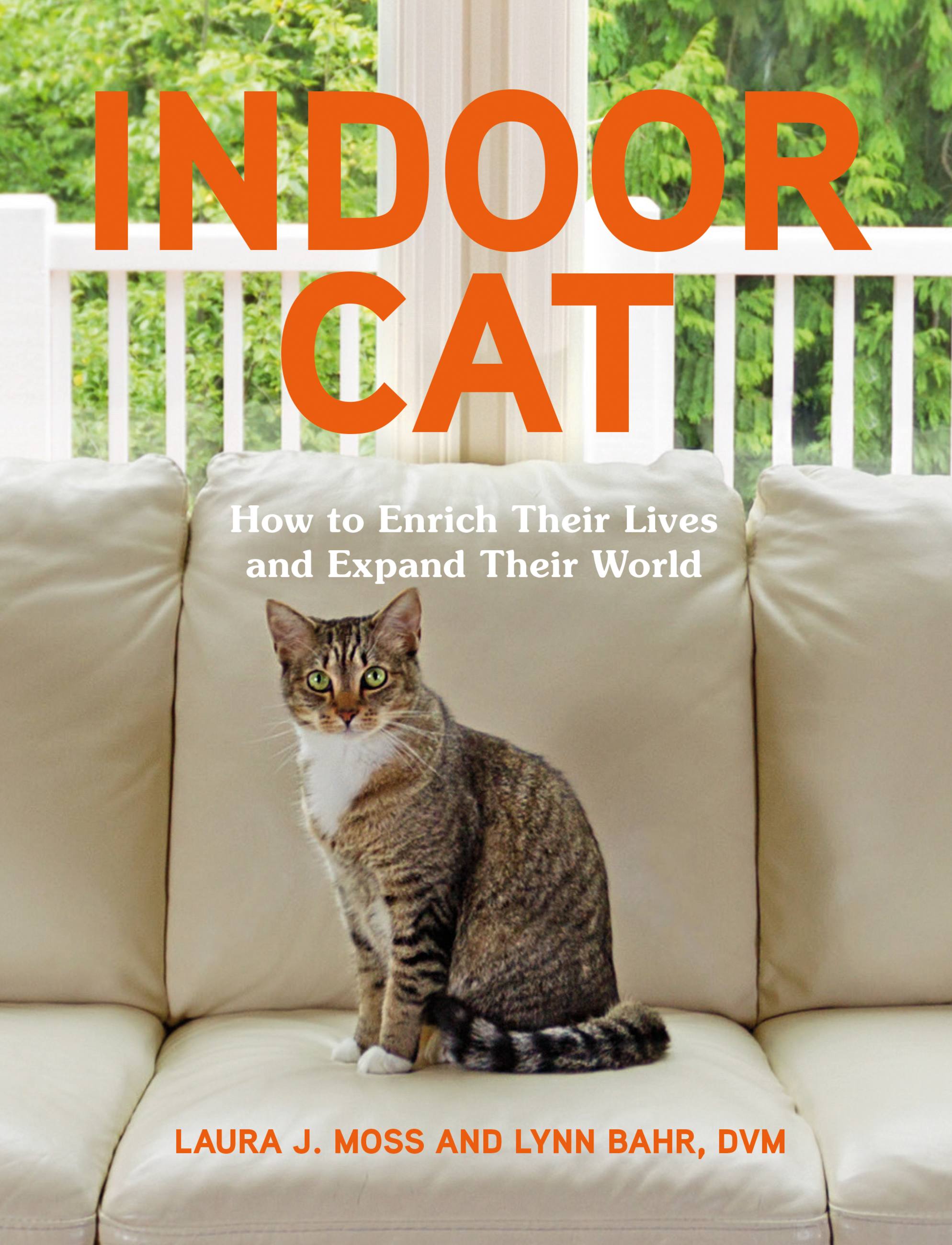

Indoor Cat

How to Enrich Their Lives and Expand Their World

Contributors

By Lynn Bahr, DVM

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2022

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762474639

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $22.00 $28.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

There are many myths our culture perpetuates about domestic cats: they live longer indoors, sleep all day, are easy and low-maintenance pets, and can't be trained. Even the most well-meaning kitty caregiver will be surprised to learn that these long-held beliefs aren't necessarily based on facts, but instead reflect the many ways we have adapted our feline friends to our indoor, domesticated lifestyles.

Indoor Cat, by Laura J. Moss, journalist and founder of Adventure Cats, and Dr. Lynn Bahr, a feline-only veterinarian, explores how to help cat owners understand a cat's perspective of their indoor homes, with practical ways to enhance cats' lives to the fullest and combat countless health and behavioral problems that result from indoor living, as well as raising the question: should every cat live exclusively indoors?

Together with scientific studies, expert opinions from vets and behaviorists, and firsthand accounts and interviews, this informative and engaging full-color guide strives to reach compassionate cat owners looking for new ways to care for and connect with their feline companions.