By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

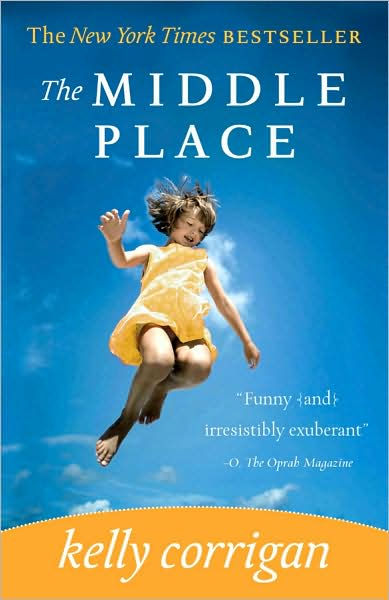

The Middle Place

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 1, 2009

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781401340933

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 1, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For Kelly Corrigan, family is everything.

At thirty-six, she had a marriage that worked, a couple of funny, active kids, and a weekly newspaper column. But even as a thriving adult, Kelly still saw herself as George Corrigan’s daughter. A garrulous Irish-American charmer from Baltimore, George was the center of the ebullient, raucous Corrigan clan. He greeted every day by opening his bedroom window and shouting, “Hello, World!” Suffice it to say, Kelly’s was a colorful childhood, just the sort a girl could get attached to.

Kelly lives deep within what she calls the Middle Place — “that sliver of time when parenthood and childhood overlap” — comfortably wedged between her adult duties and her parents’ care. But she’s abruptly shoved into a coming-of-age when she finds a lump in her breast — and gets the diagnosis no one wants to hear. And so Kelly’s journey to full-blown adulthood begins. When George, too, learns he has late-stage cancer, it is Kelly’s turn to take care of the man who had always taken care of her — and show us a woman as she finally takes the leap and grows up.

Kelly Corrigan is a natural-born storyteller, a gift you quickly recognize as her father’s legacy, and her stories are rich with everyday details. She captures the beat of an ordinary life and the tender, sometimes fractious moments that bind families together. Rueful and honest, Kelly is the prized friend who will tell you her darkest, lowest, screwiest thoughts, and then later, dance on the coffee table at your party.

Funny, yet heart-wrenching, The Middle Place is about being a parent and a child at the same time. It is about the special double-vision you get when you are standing with one foot in each place. It is about the family you make and the family you came from — and locating, navigating, and finally celebrating the place where they meet. It is about reaching for life with both hands — and finding it.

-

"If you're in a book club or just love to read, make sure this book ends up in your lap, where it will remain until you finish. Plan to laugh, cry, and be consumed by Kelly Corrigan."Winston-Salem Journal

-

"Bravely reveals the frightened daughter inside the grown-up wife and mother."Elle

-

"Come for the writing, stay for the drama. Or vice-versa. Either way, you won't regret it."San Francisco Chronicle

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use