Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

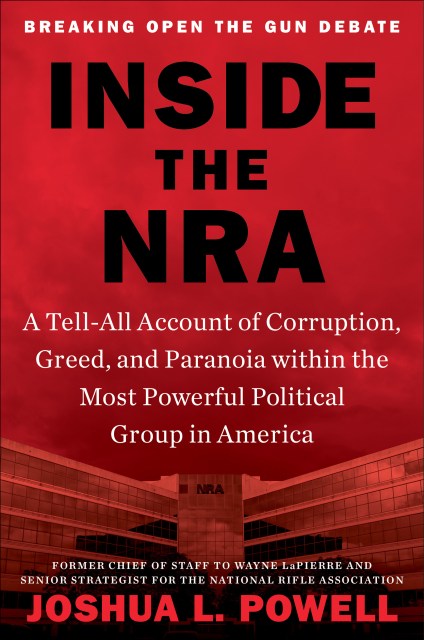

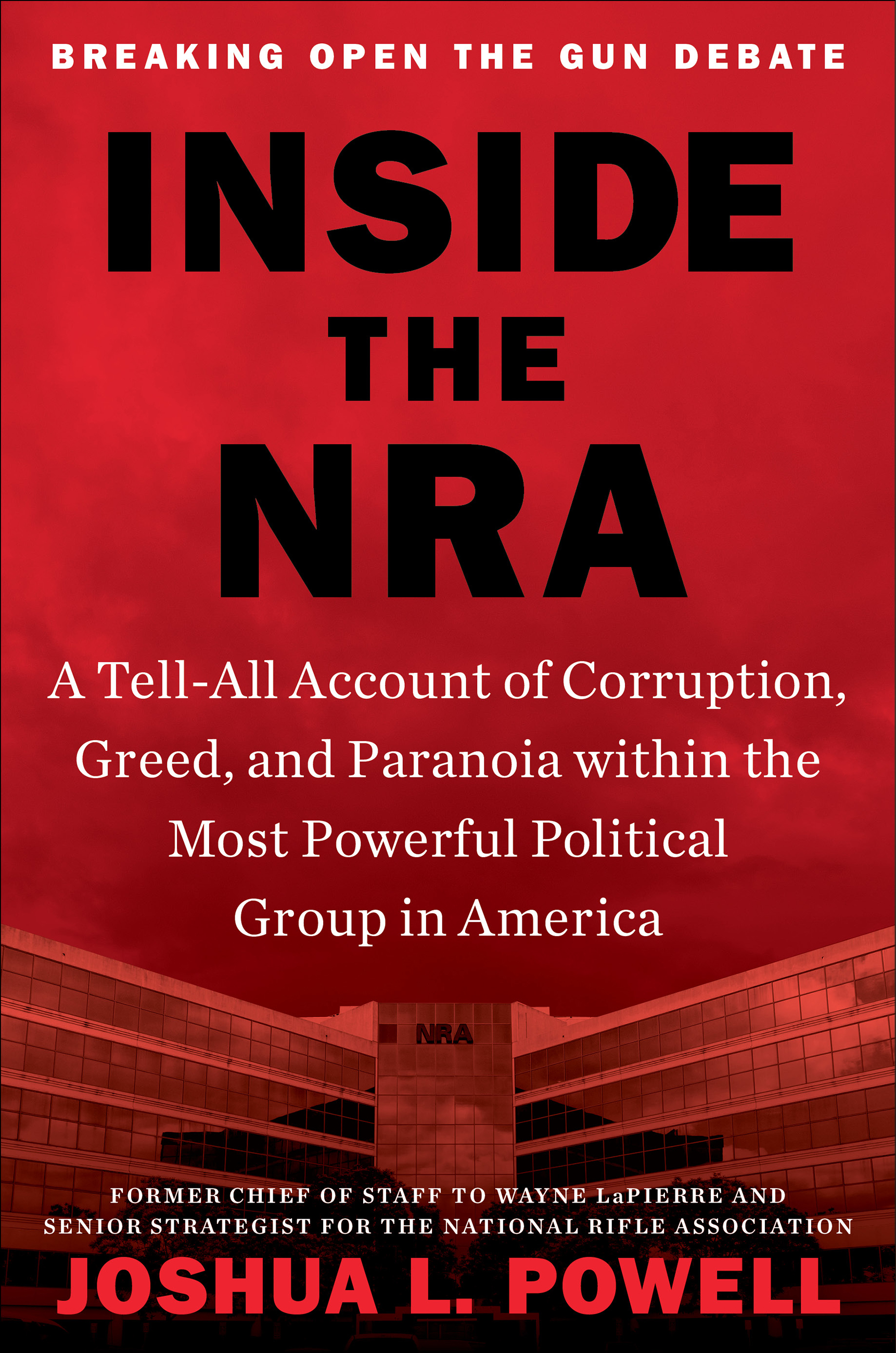

Inside the NRA

A Tell-All Account of Corruption, Greed, and Paranoia within the Most Powerful Political Group in America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 8, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538737255

Price

$37.00Price

$48.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $37.00 $48.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 8, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Joshua L. Powell is the NRA–a lifelong gun advocate, in 2016, he began his new role as a senior strategist and chief of staff to NRA CEO Wayne LaPierre.

What Powell uncovered was horrifying: “the waste and dysfunction at the NRA was staggering.”

INSIDE THE NRA reveals for the first time the rise and fall of the most powerful political organization in America–how the NRA became feared as the Death Star of Washington lobbies and so militant and extreme as “to create and fuel the toxicity of the gun debate until it became outright explosive.”

INSIDE THE NRA explains this intentional toxic messaging was wholly the product of LaPierre’s leadership and the extremist branding by his longtime PR puppet master Angus McQueen. In damning detail, Powell exposes the NRA’s plan to “pour gasoline” on the fire in the fight against gun control, to sow discord to fill its coffers, and to secure the presidency for Donald J. Trump.