By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

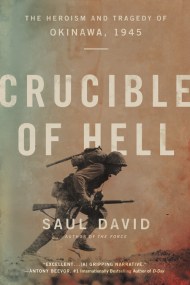

Bloody Okinawa

The Last Great Battle of World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 20, 2021

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903205

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 20, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

On Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, more than 184,000 US troops began landing on the only Japanese home soil invaded during the Pacific war. Just 350 miles from mainland Japan, Okinawa was to serve as a forward base for Japan’s invasion in the fall of 1945.

Nearly 140,000 Japanese and auxiliary soldiers fought with suicidal tenacity from hollowed-out, fortified hills and ridges. Under constant fire and in the rain and mud, the Americans battered the defenders with artillery, aerial bombing, naval gunfire, and every infantry tool. Waves of Japanese kamikaze and conventional warplanes sank 36 warships, damaged 368 others, and killed nearly 5,000 US seamen.

When the slugfest ended after 82 days, more than 125,000 enemy soldiers lay dead—along with 7,500 US ground troops. Tragically, more than 100,000 Okinawa civilians perished while trapped between the armies. The brutal campaign persuaded US leaders to drop the atomic bomb instead of invading Japan.

Utilizing accounts by US combatants and Japanese sources, author Joseph Wheelan endows this riveting story of the war’s last great battle with a compelling human dimension.

-

"In Bloody Okinawa Joseph Wheelan presents us with a rich narrative tapestry of the final great battle of World War II. To cite Wheelan himself, his book's 'scenes of nearly indescribable carnage' mixed with his insightful knowledge of military history are as breathtaking as they are unforgettable. This book belongs not only on the shelves of readers World War II non-fiction, but in the library of anyone interested in the horror, bravery, and compassion that total war brings out in American fighting men."BobDrury and Tom Clavin, bestselling authors of The Last Stand of Fox Company, Halsey's Typhoon, and The Heart of Everything That Is

-

"Bloody Okinawa puts the reader in the heart one of the war's largest battles through the eyes of the soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen who experienced the fighting firsthand. Wheelan also captures the perspective of the civilians and Japanese. Storming Japanese pill boxes and relentless kamikaze attacks punctuate a narrative that places the reader in the vortex of this enormous struggle. Gripping and harrowing, the book brings to life the battle so savage that it influenced America's decision to drop the atomic bomb."PatrickK. O'Donnell, award-winning and bestselling author of The Unknowns: The Untold Story of American's Unknown Soldier and WWI'sMost Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home

-

"Wheelan mines a wealth of source material to present a 360-degree view of the battle, and maintains a brisk pace.... Exhaustive yet accessible"Publishers Weekly

-

"A fine history of an iconic battle... Wheelan delivers excellent analyses and anecdotes and biographies of individuals from both sides."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Wheelan's book Bloody Okinawa describes [the battle], and its subtitle--"The Last Great Battle of World War II"--is deserved."New York Daily News

-

"Whelan does a deft job of blending ground and naval actions with the Japanese accounts of the battle, writing a gripping and timely account."New York Journal of Books

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use