Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

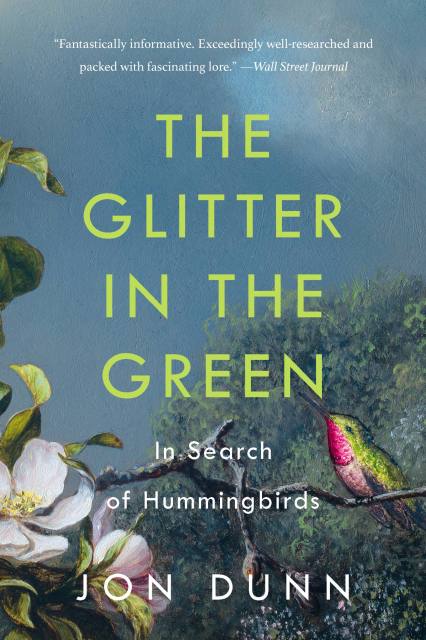

The Glitter in the Green

In Search of Hummingbirds

Contributors

By Jon Dunn

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 20, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541618183

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 20, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An acclaimed natural history writer follows the trail of the remarkable hummingbird all over the world.

Hummingbirds are a glittering, sparkling collective of over three hundred wildly variable species. For centuries, they have been revered by indigenous Americans, coveted by European collectors, and admired worldwide for their unsurpassed metallic plumage and immense character. Yet they exist on a knife-edge, fighting for survival in boreal woodlands, dripping cloud forests, and subpolar islands. They are, perhaps, the ultimate embodiment of evolution's power to carve a niche for a delicate creature in even the harshest of places.

Traveling the full length of the hummingbirds' range, from the cusp of the Arctic Circle to near-Antarctic islands, acclaimed nature writer Jon Dunn encounters birders, scientists, and storytellers in his quest to find these beguiling creatures, immersing us in the world of one of Earth's most charismatic bird families.

Hummingbirds are a glittering, sparkling collective of over three hundred wildly variable species. For centuries, they have been revered by indigenous Americans, coveted by European collectors, and admired worldwide for their unsurpassed metallic plumage and immense character. Yet they exist on a knife-edge, fighting for survival in boreal woodlands, dripping cloud forests, and subpolar islands. They are, perhaps, the ultimate embodiment of evolution's power to carve a niche for a delicate creature in even the harshest of places.

Traveling the full length of the hummingbirds' range, from the cusp of the Arctic Circle to near-Antarctic islands, acclaimed nature writer Jon Dunn encounters birders, scientists, and storytellers in his quest to find these beguiling creatures, immersing us in the world of one of Earth's most charismatic bird families.

Genre:

-

“Fantastically informative… The Glitter in the Green braids the cultural history and daunting needs and feats of these wondrous birds with vivid accounts of the author’s sometimes hazardous, far-flung mountain, forest and island expeditions… Exceedingly well-researched and packed with fascinating lore, it should appeal to avid birders and general readers alike.”Wall Street Journal

-

“Dunn combines an intense emotional response to the radiant appearance of each transfixing bird… [He] fuses vivid metaphor and close observation.”New York Review of Books

-

“Natural history writer, photographer and hummingbird obsessive (within the first hundred pages he crosses both a bear and a puma in pursuit of this tiny, glimmering bird) Jon Dunn has written a book that is both an ode to hummingbirds and a remarkable piece of travel literature.”BookPage

-

“Hummingbirds must be among the most beautiful organisms on Earth. Yet for anyone who has never seen one in the flesh, it is difficult to convey the psychological effects of a first encounter… A good place to begin to understand the birds’ dramatic pleasures is with this entertaining book. One of Jon Dunn’s real achievements is his ability to conjure the plastic form and astonishing chromatic architecture of many hummingbird species.”The Spectator

-

“Full of natural history, quotes from early explorers, local history, and adventure, Dunn’s chronicle of his hummingbird quests will make readers just as obsessed with these small, quick birds dipped in rainbows.”Booklist

-

“The Glitter In The Green contains astonishing photographs and stories about these rare and beautiful birds.”The Herald (Scotland)

-

“At times a thriller, the history of hummingbirds in art, religion, and superstition—past and present—is fascinating, enlightening, and entertainingly informative to those of us who are smitten with them.”Bird Watcher’s Digest

-

“Natural history writer Dunn takes readers on a wondrous globe-trotting pilgrimage to seek out hummingbirds as their populations are threatened... Dunn’s vivid prose, balanced with just the right amount of detail, will captivate birders and non-birders alike.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Dunn chronicles his travels from his home in the Shetland Islands to the Americas in search of this alluring bird.... A mesmerizing, wonder-filled nature study that also serves as a cautionary tale about wildlife conservation.”Kirkus

-

“An engaging history of the species… This inviting narrative describes the author’s search for the rare Mangrove Hummingbird in Costa Rica, as well as others threatened with habitat loss in Cuba and Mexico… Notably, the author takes care to consider the place of hummingbirds in the history, literature, and cultures of their locales. Dunn writes passionately…”Library Journal

-

“Jon Dunn’s book is an adventure-filled, continent-spanning travelogue. It is also meticulously researched. By carefully peeling back layers of history to find shimmering hummingbirds hidden within, Dunn has created essential reading to understand human obsession—past and present—with these remarkable creatures.”Jonathan C. Slaght, author of Owls of the Eastern Ice: A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl

-

“Glittering gems of the Americas and nowhere else on Earth, hummingbirds lure Jon Dunn from Alaska to Chile in this whizzing travelogue of hummer natural history. In an adventure replete with pop culture and literary references, Dunn treks deserts and jungles, investigates a slaughter of hummingbirds for love potions, unmasks the real James Bond, and in Colombia sees an otherworldly hummer, ‘like some enameled god fallen to earth.’ The book is that exquisite.”Dan Flores, author of the New York Times bestseller Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History

-

“More than just an observant birdwatcher, Jon Dunn is a talented traveler and writer, capturing just the right details of people and place to make his hummingbird odyssey come alive. The Glitter in the Green is a vivid exploration of a dazzling subject.”Thor Hanson, author of Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

-

“This is more than a bird book, but still, it is. It combines one person’s adventure with arguably the most spectacular group of birds in the world: hummingbirds! The immensely talented writer Jon Dunn follows these highly diverse jewels from Alaska, down the Americas to Tierra del Fuego, and weaves an environmental and cultural dialogue around these hummers and the human-dominated world they live in.”Joel Cracraft, Curator in Charge, Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History