By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Literary Landscapes

Charting the Worlds of Classic Literature

Contributors

Edited by John Sutherland

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 13, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316561815

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

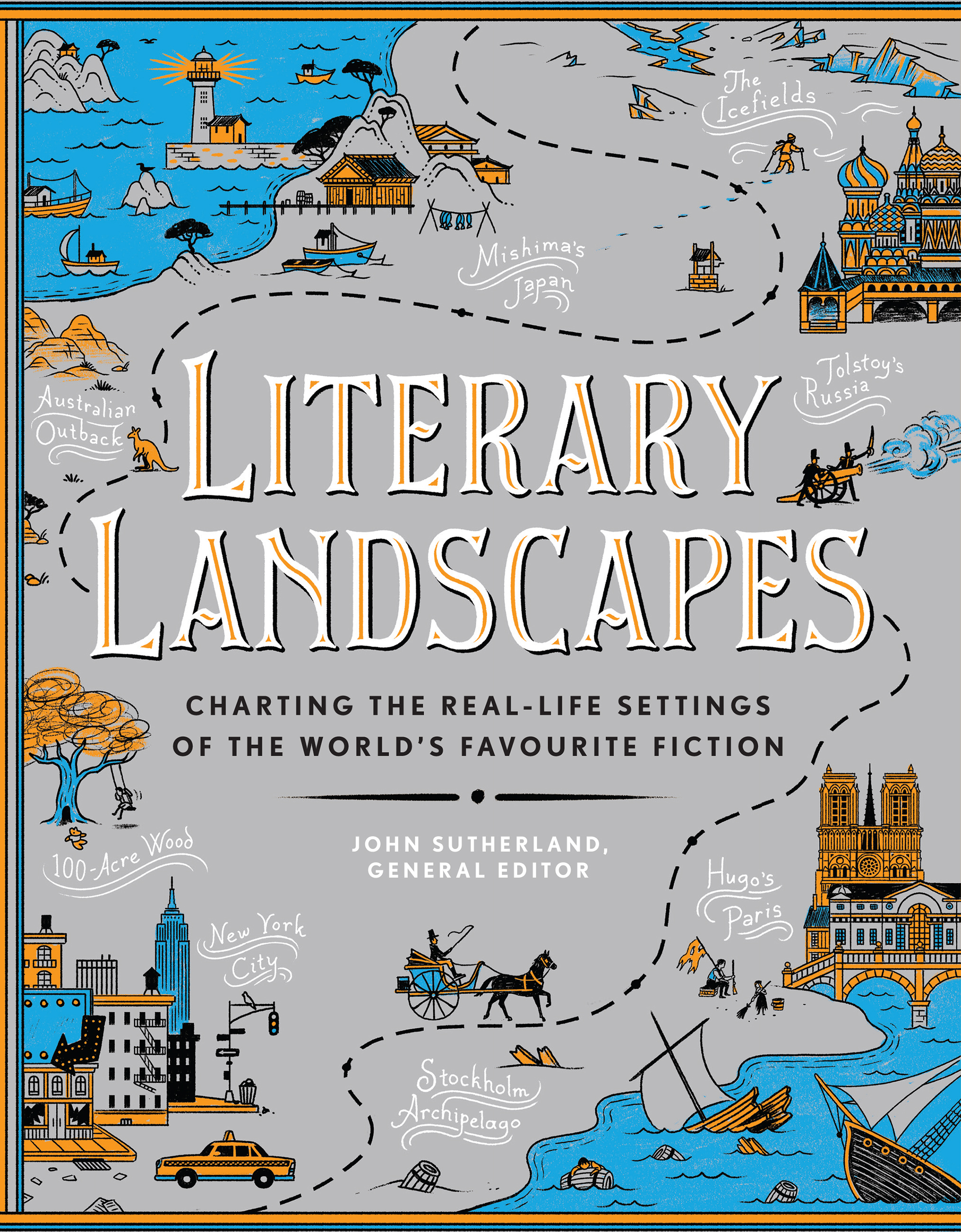

Some stories couldn’t happen just anywhere. As is the case with all great literature, the setting, scenery, and landscape are as central to the tale as any character, and just as easily recognized. Literary Landscapes brings together more than 50 literary worlds and examines how their description is intrinsic to the stories that unfold within their borders.

Follow Leopold Bloom’s footsteps around Dublin. Hear the music of the Mississippi River steamboats that set the score for Huckleberry Finn. Experience the rugged bleakness of Newfoundland in Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News or the soft Neapolitan breezes in My Brilliant Friend.

The landscapes of enduring fictional characters and literary legends are vividly brought to life, evoking all the sights and sounds of the original works. Literary Landscapes will transport you to the fictions greatest lands and allow you to connect to the story and the author’s intent in a whole new way.

Series:

-

"Part of the attraction of most classic novels is their strong sense of place... [Literary Landscapes] delves into the geography, location, and terrain of 50 beloved books - from Joyce's Dublin to Harper Lee's Monroeville, Ala."The New York Times Book Review, 'New & Noteworthy'

-

"Deep dive into the inner workings of your favorite literary world in this beautiful coffee table book."The New York Post

-

"[Literary Landscapes] is gorgeously illustrated, wide-ranging, and very pleasingly idiosyncratic.... Readers will be reminded throughout of what a vital role location plays in virtually everything they read, and the generous artwork of Literary Landscapes will help to send that reminder home."Open Letters Review

-

"This fascinating (and beautifully designed) book looks at how novels' settings impact their plot, character, and tone."Refinery29

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use