By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

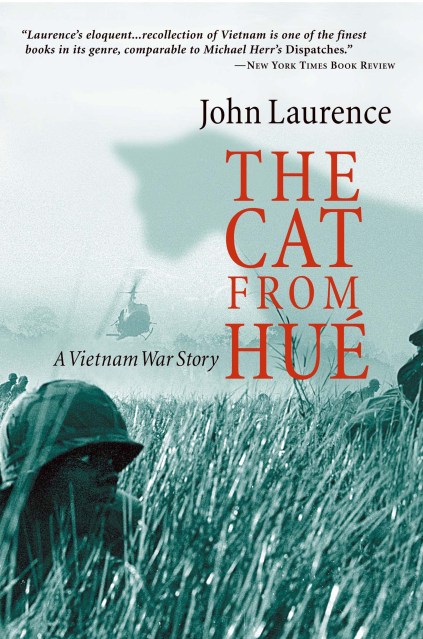

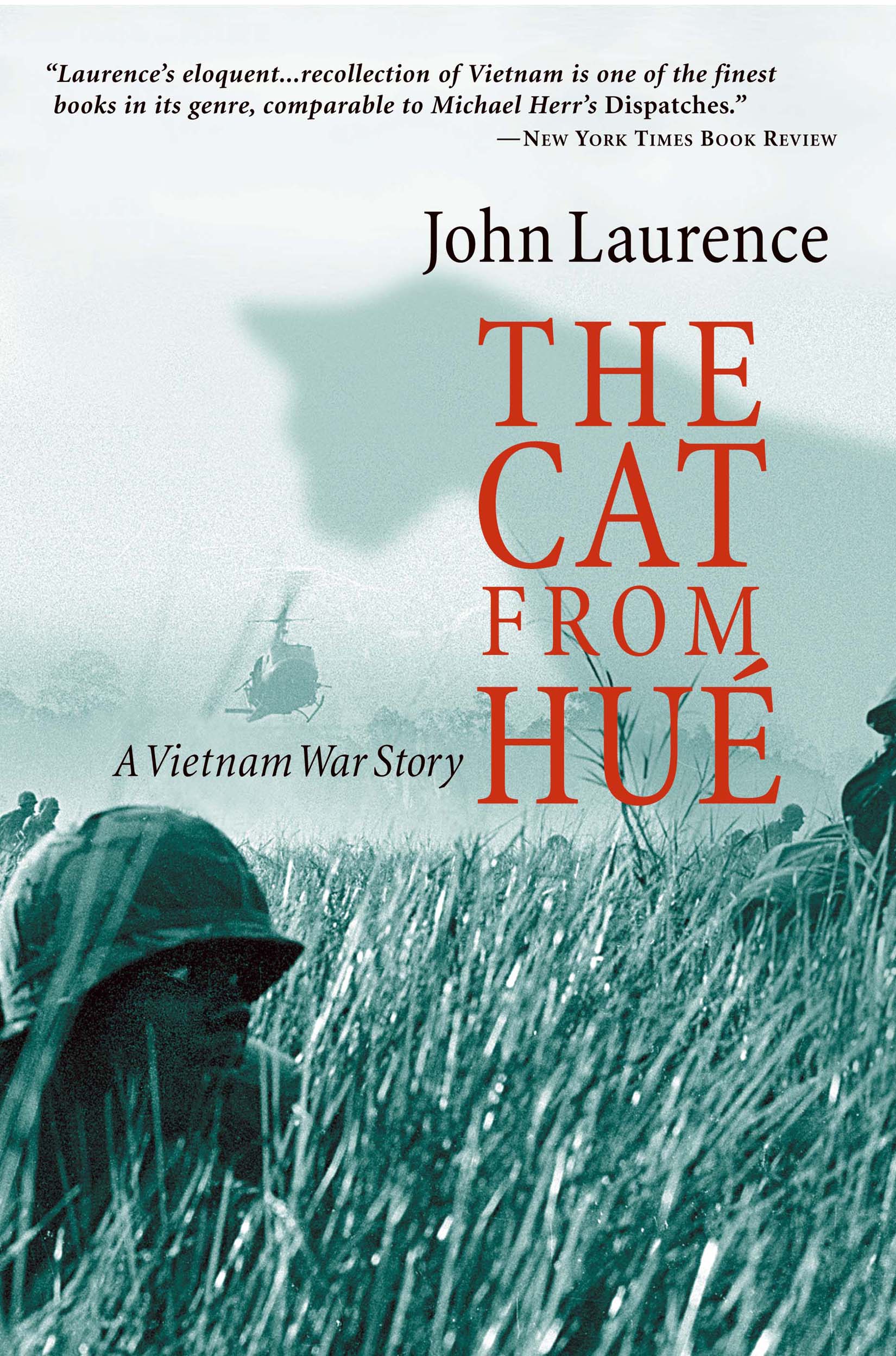

The Cat From Hue

A Vietnam War Story

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 5, 2008

- Page Count

- 864 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786724680

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $35.99 $45.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 5, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

John Laurence covered the Vietnam war for CBS News from its early days, through the bloody battle of Hue in 1968, to the Cambodian invasion. He was judged by his colleagues to be the best television reporter of the war, however, the traumatic stories Laurence covered became a personal burden that he carried long after the war was over.

In this evocative, unflinching memoir, laced with humor, anger, love, and the unforgettable story of Mé a cat rescued from the battle of Hue, Laurence recalls coming of age during the war years as a journalist and as a man. Along the way, he clarifies the murky history of the war and the role that journalists played in altering its course.

The Cat from Huéi> has earned passionate acclaim from many of the most renowned journalists and writers about the war, as well as from military officers and war veterans, book reviewers, and readers. This book will stand with Michael Herr’s Dispatches, Philip Caputo’s A Rumor of War, and Neil Sheehan’s A Bright, Shining Lie as one of the best books ever written about Vietnam-and about war generally.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use