By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

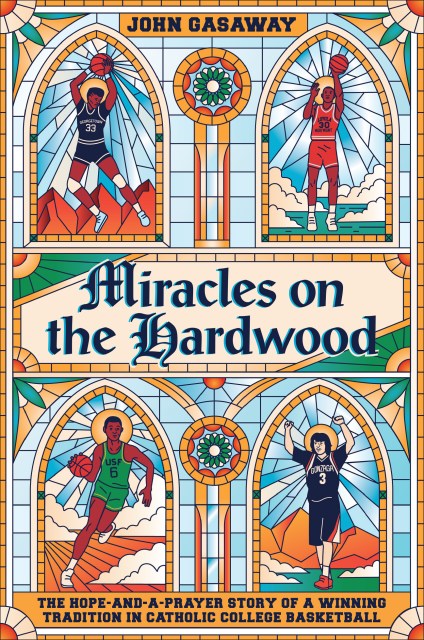

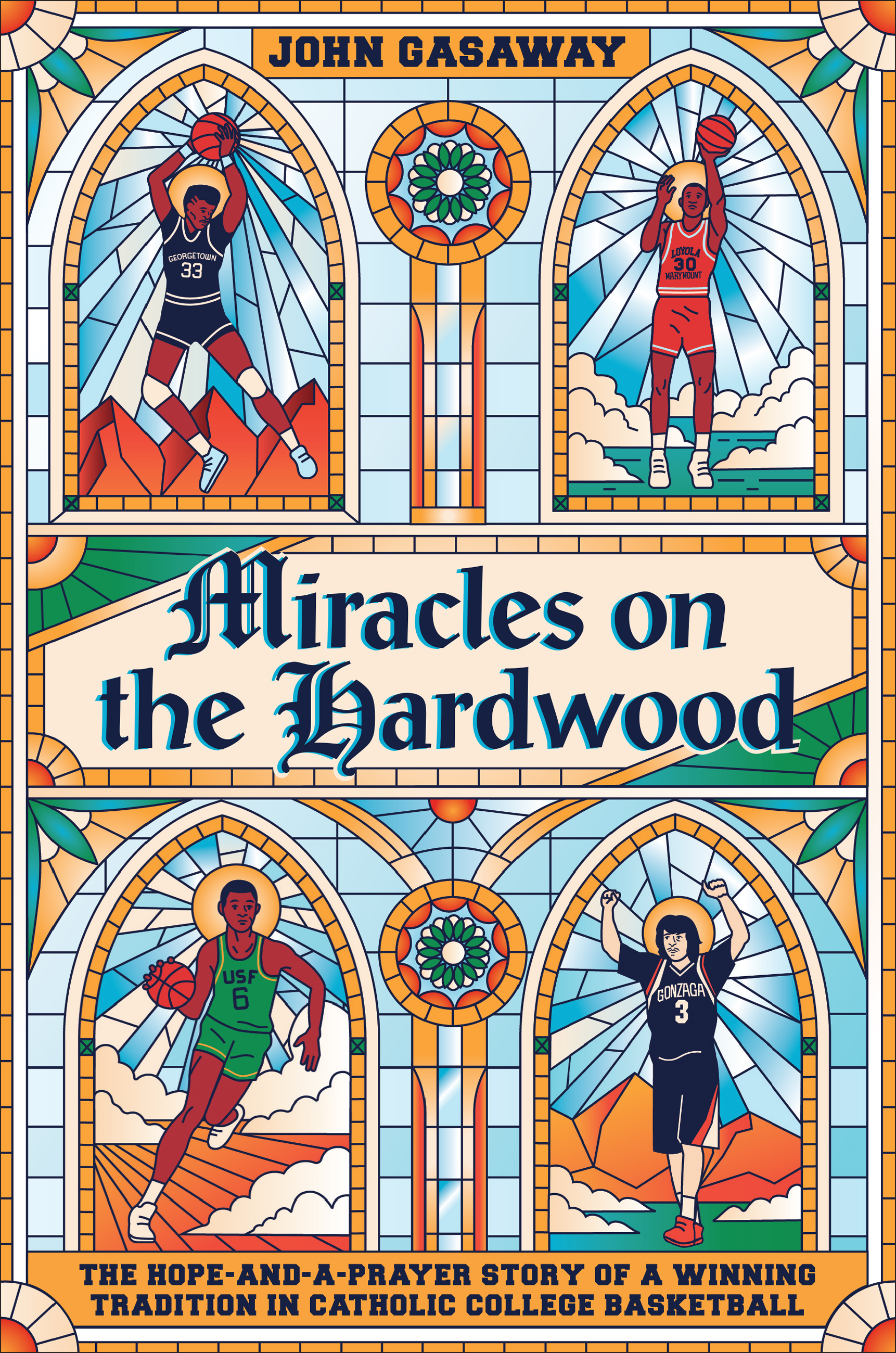

Miracles on the Hardwood

The Hope-and-a-Prayer Story of a Winning Tradition in Catholic College Basketball

Contributors

By John Gasaway

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538717127

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In MIRACLES ON THE HARDWOOD, author John Gasaway traces the rise of Catholic college basketball—from its early days (Villanova made an appearance in the Final Four in the first NCAA tournament in 1939) to the dominance of the San Francisco Dons in the 1950s and the ascendance of powerhouses Georgetown, Villanova, and Gonzaga—through their decades-long rivalries and championship games. Featuring interviews with notable coaches, players, alums, and fans—including Loyola Chicago's most famous and dedicated fan, 100-year-old Sister Jean—to get at the heart of how these universities have excelled at this sport.

Small in number but devout in the game's spirit, these teams have made the miraculous a matter of ritual, and their greatest works may be yet to come.

-

"As someone who coached at a Catholic school, the University of Detroit Titans, I appreciate the in-depth look at the history of Catholic schools on the hardwood. John Gasaway does a masterful job of capturing the many miracles that have taken place. It is a fantastic read, 'Awesome Baby' with a Capital A!"Dick Vitale

-

“John Gasaway captures the essence of basketball as religion in MIRACLES ON THE HARDWOOD. From Bill Russell and USF to Mark Few and Gonzaga to Jay Wright and Villanova, Catholic schools have had tremendous success and are woven into the fabric of the game. My confession? I would have sinned if I hadn’t read this book. If you love the game, Gasaway illuminates its rich history in MIRACLES ON THE HARDWOOD."Jay Bilas, ESPN

-

"John Gasaway has always covered basketball with mathematical precision and religious fervor. That makes him the perfect author to lay out a historical narrative that feels both sweeping and intimate. It might seem like divine providence that has enabled so many Catholic schools to produce winning basketball teams, but Gasaway neatly lays out the cultural, economic and competitive factors that have allowed that to happen, with all the color and entertainment you would expect from this cast of characters. Whether you are a Don, a Zag, a Hoya or a Rambler, this book will send you on a heavenly journey."Seth Davis, author of WOODEN: A Coach's Life

-

"Catholic colleges and universities became part of the fabric of the game soon after its invention by Dr. Naismith. Gasaway takes you on an entertaining journey through the history of the greatest teams, players, and coaches—not to mention characters—that have ever graced the hardwood. You’ll recognize them all and, like me, you won’t be able to put this book down."Fran Fraschilla

-

"The subject is close to my heart, and MIRACLES ON THE HARDWOOD gives it historical love that’s long overdue. Meticulous, comprehensive, and erudite in true Gasaway fashion, fans of the underdog will fly through this narrative and be better for it."Joe Lunardi

-

"Of hoops, hopes, holy orders, and habits...mysterious and sometimes miraculous...Fans of college roundball, parochial or not, will enjoy Gasaway’s lively history."Kirkus

-

“An ambitious historical re-telling of the whole of college basketball history…MIRACLES ON THE HARDWOOD is a great book.”Ball & Order

-

“MIRACLES ON THE HARDWOOD will serve as a vital reference on the topic.”Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use