By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

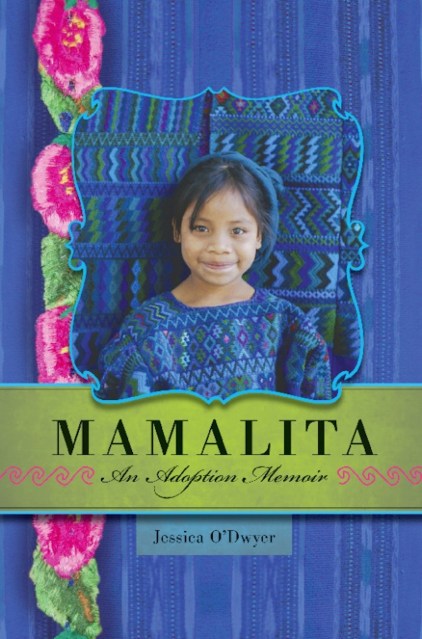

Mamalita

An Adoption Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 19, 2010

- Page Count

- 312 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580053839

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 19, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This gripping memoir details an ordinary American woman's quest to adopt a baby girl from Guatemala in the face of overwhelming adversity. At only 32 years old, Jessica O'Dwyer experiences early menopause, seemingly ending her chances of becoming a mother. Years later, married but childless, she comes across a photo of a two-month-old girl on a Guatemalan adoption website, and feels an instant connection.

From the get-go, Jessica and her husband face numerous and maddening obstacles. After a year of tireless efforts, Jessica finds herself abandoned by her adoption agency; undaunted, she quits her job and moves to Antigua so she can bring her little girl to live with her and wrap up the adoption, no matter what the cost. Eventually, after months of disappointments, she finesses her way through the thorny adoption process and is finally able to bring her new daughter home.

Mamalita is as much a story about the bond between a mother and child as it is about the lengths adoptive parents go to in their quest to bring their children home. At turns harrowing, heartbreaking, and inspiring, this is a classic story of the triumph of a mother's love over almost insurmountable odds.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use