By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

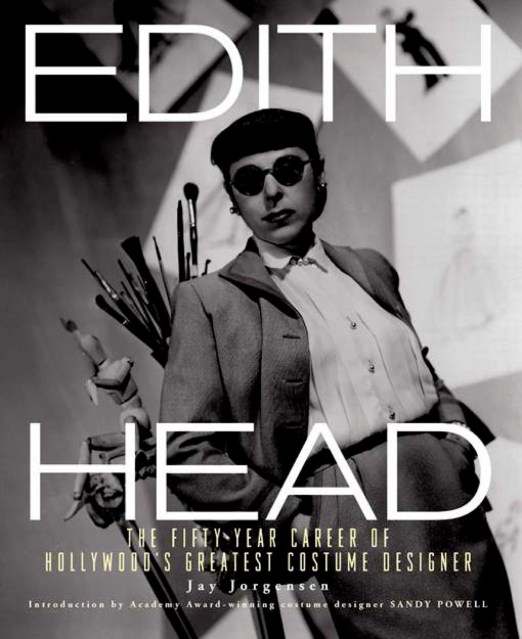

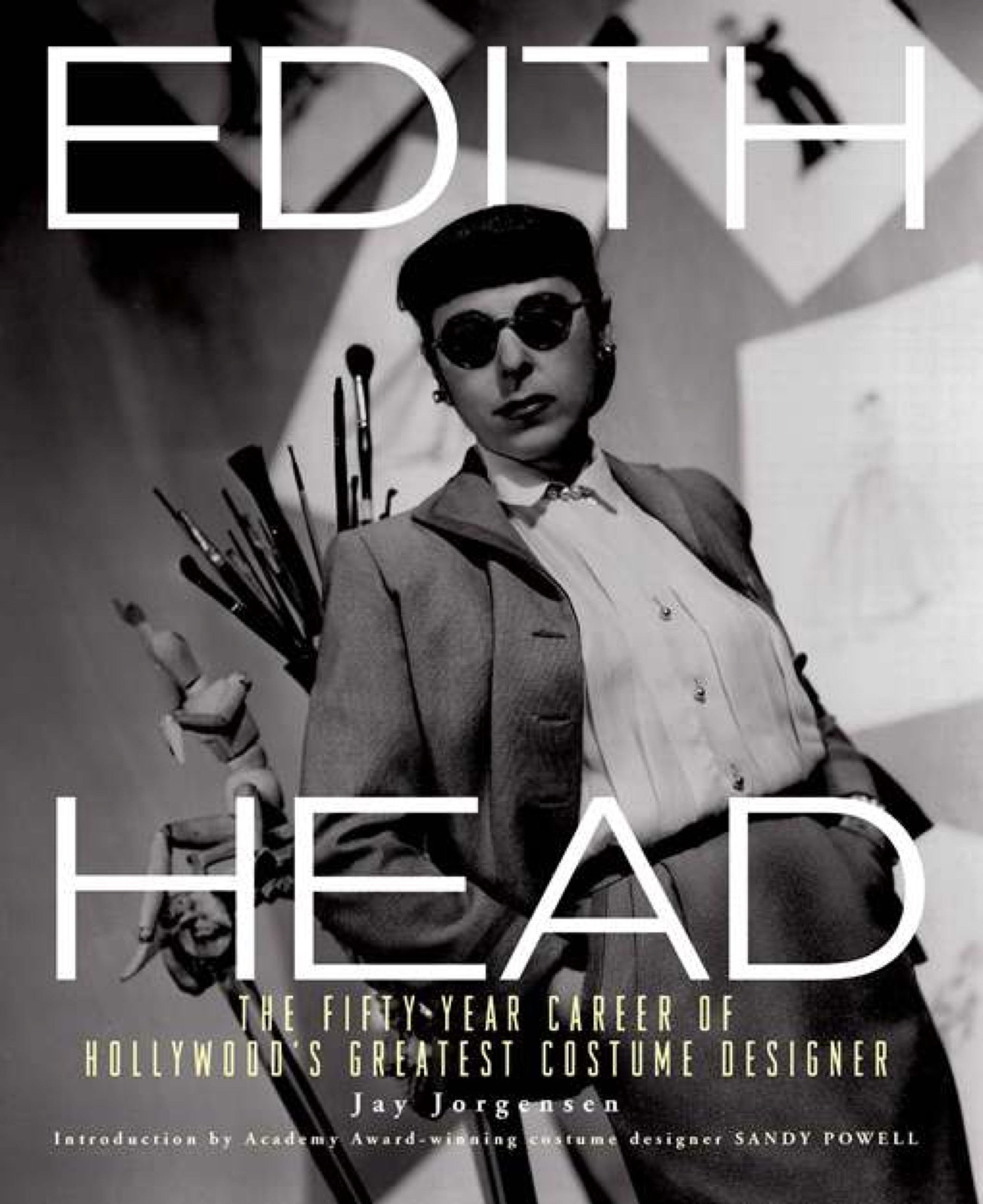

Edith Head

The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood's Greatest Costume Designer

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 5, 2010

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762441730

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $80.00 $102.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 5, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Never before has the account of Hollywood’s most influential designer been so thoroughly revealed — because never before have the Edith Head Archives of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences been tapped. This unprecedented access allows this book to be a one-of-a-kind survey, bringing together a spectacular collection of rare and never-before-seen sketches, costume test shots, behind-the- scenes photos, and ephemera.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use