By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

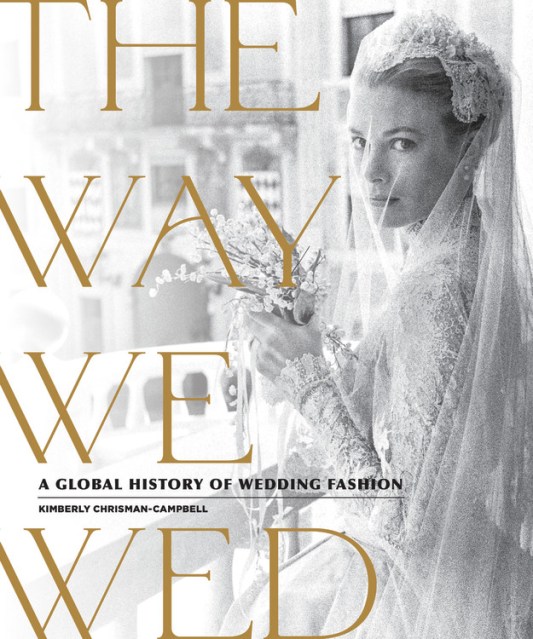

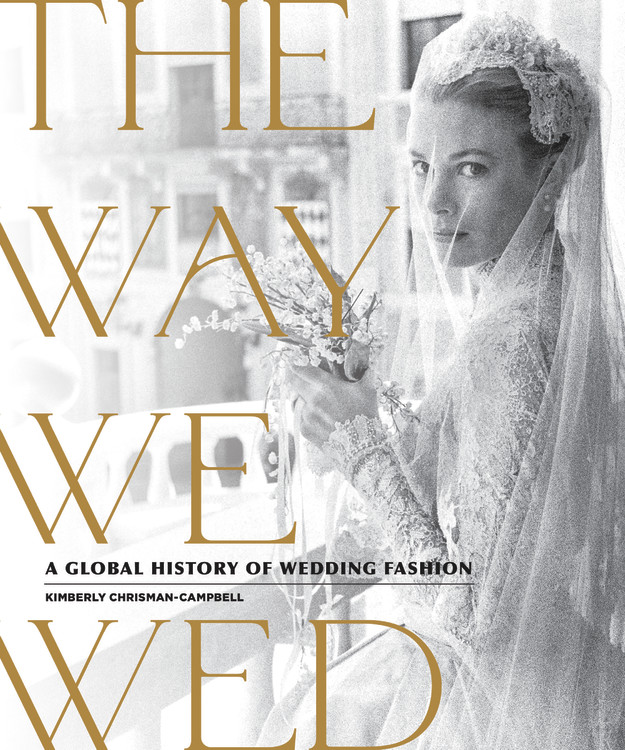

The Way We Wed

A Global History of Wedding Fashion

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 1, 2020

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762470303

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 1, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For fashion buffs, romantics, and brides-to-be, a fascinating collection of wedding garb and glamour through pop culture and history.

The Way We Wed: A History of Wedding Fashion presents styles and stories from the Renaissance to the present day, chronicling evolving fashions, classes, and expectations. And because all wedding attire has a tale to tell, The Way We Wed also reveals fascinating personal stories of those who wore it.

While the book is a rich source of bridal inspiration for all seasons, it’s far from a monotonous parade of white gowns. The Way We Wed showcases wedding gowns of all colors and styles from around the world, as well as going-away dresses, accessories (shoes, veils, hats, and tiaras), and clothes worn by flower girls, bridesmaids, mothers of the bride, and grooms. Same-sex weddings are represented along with royal weddings, wartime brides, White House weddings, remarriage, Hollywood weddings, and more. The book features celebrity and historical couples as well as everyday people. A few of the included names:

While the book is a rich source of bridal inspiration for all seasons, it’s far from a monotonous parade of white gowns. The Way We Wed showcases wedding gowns of all colors and styles from around the world, as well as going-away dresses, accessories (shoes, veils, hats, and tiaras), and clothes worn by flower girls, bridesmaids, mothers of the bride, and grooms. Same-sex weddings are represented along with royal weddings, wartime brides, White House weddings, remarriage, Hollywood weddings, and more. The book features celebrity and historical couples as well as everyday people. A few of the included names:

- Angelina Jolie

- Frida Kahlo

- Elizabeth Taylor

- Princess Diana

- Martha Washington

- Solange Knowles

- Ellen DeGeneres

- Meghan Markle

Illustrated with 100 gorgeous photos, The Way We Wed is a rich celebration of the art of wedding fashion across time and cultures, and those whose style and circumstances made a statement.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use