Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

John Quincy Adams

Militant Spirit

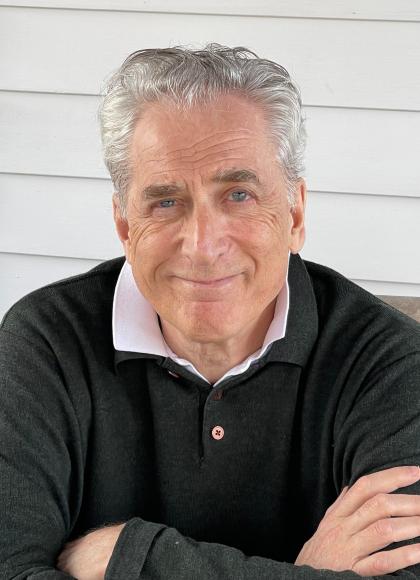

Contributors

By James Traub

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2017

- Page Count

- 656 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093830

Price

$22.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

- Digital download $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A splendid new biography …. Reliably thorough, blissfully bereft of jargon, and nicely paced.”―New York Times Book Review

Few figures in American history have held as many roles in public life as John Quincy Adams. The son of John Adams, he was a brilliant ambassador and secretary of state, a frustrated president, and a dedicated congressman who staunchly opposed slavery.

In John Quincy Adams, scholar and journalist James Traub draws on Adams’s diaries, letters, and writings to evoke his numerous achievements-and failures-in office. A man of unwavering moral convictions, Adams is the father of foreign policy “realism” and one of the first proponents of the “activist government.” But John Quincy Adams is first and foremost the story of a brilliant, flinty, and unyielding man whose life exemplified admirable political courage.

-

"A splendid new biography.... Reliably thorough, blissfully bereft of jargon, and nicely paced."Joseph J. Ellis, New York Times Book Review

-

"James Traub does justice to both the man and his times, with a historian's sense of complexity and a writer's eye for drama and detail."Sean Wilentz

-

"By rights, John Quincy Adams should be one of America's most famous presidents. His life story is remarkable, the son of one of the nation's founding presidents, the only one to serve in an elected office after leaving the White House, and a man of vast intelligence and political courage who died while debating in the House of Representatives. Yet he's an obscure figure. James Traub has rectified this in a book worthy of its subject."Fareed Zakaria, Fareed Zakaria GPS

-

"Traub's work is a reminder to Americans that politicians can be devoted to national issues, promote their principles, and still maintain their integrity."Choice

-

"Well-written and highly readable biography...highly accessible work."Chronicles

-

"[An] excellent biography.... [John Quincy Adams'] life is worth meditating on, and Traub's biography is an indispensable resource for doing so."Washington Free Beacon

-

"James Traub has admirably captured the man inside the public figure, giving us a view of a typical New England grandee, puritanical at his core, molded as a traditionalist republican with no love for pure democracy, convinced that governing was intended for the class born and bred for it."The Arts Fuse

-

"Traub thoroughly, even quite engagingly, follows Adams through the years during which he served in the diplomatic corps, building up the reputation as the new republic's best representative abroad."Booklist,starred review

-

"[An] essential biography of a complex man.... Traub shows that without imperiling national unity, Adams's persistent, perspicacious opposition to slavery 'shattered the overweening confidence of the South' and confirmed his place in America's history."Publishers Weekly,starred review

-

"Traub depicts a fully fleshed character, an extraordinary man driven by his birthright principles, a voluminous diarist, scholar, poet, polymath, eccentric, and iconoclast. The author also offers a masterly portrait of Adams' wife, Louisa. An impassioned biography of 'a coherent and consistent thinker who adhered to his core political convictions across his decades of public service.'"Kirkus

-

"James Traub's new biography of John Quincy Adams is exceptionally strong. Adams was a complicated hero, a patrician visionary but also, as Traub puts it, a militant spirit, one of the most important diplomats in all of American history and, finally, slavery's greatest enemy in American politics."Sean Wilentz, author of The Rise of AmericanDemocracy: Jefferson to Lincoln

-

"John Quincy Adams was a great statesman and a heroic crusader for freedom, whose finest hours, ironically, came both before and after his time as president. James Traub does us a service by bringing him to life again for a new generation. With a journalist's touch, Traub paints a vivid portrait of the man in all his complexity."Robert Kagan, author of Of Paradise and Power

-

"In lucid prose and with canny insight, James Traub illuminates the life and political career of John Quincy Adams. Driven by grim purpose and consistent values, Adams was hard to love but demanded respect as he matured into a champion of liberty for all. Traub admires Adams [and is] tinged with sadness for the absence of his type in our own times."Alan Taylor, author of The Internal Enemy:Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832