By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

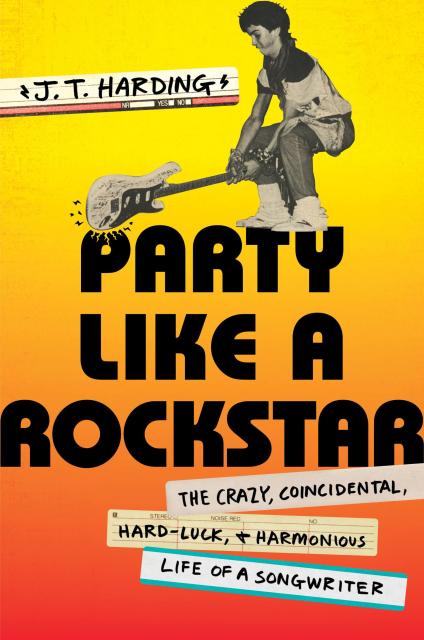

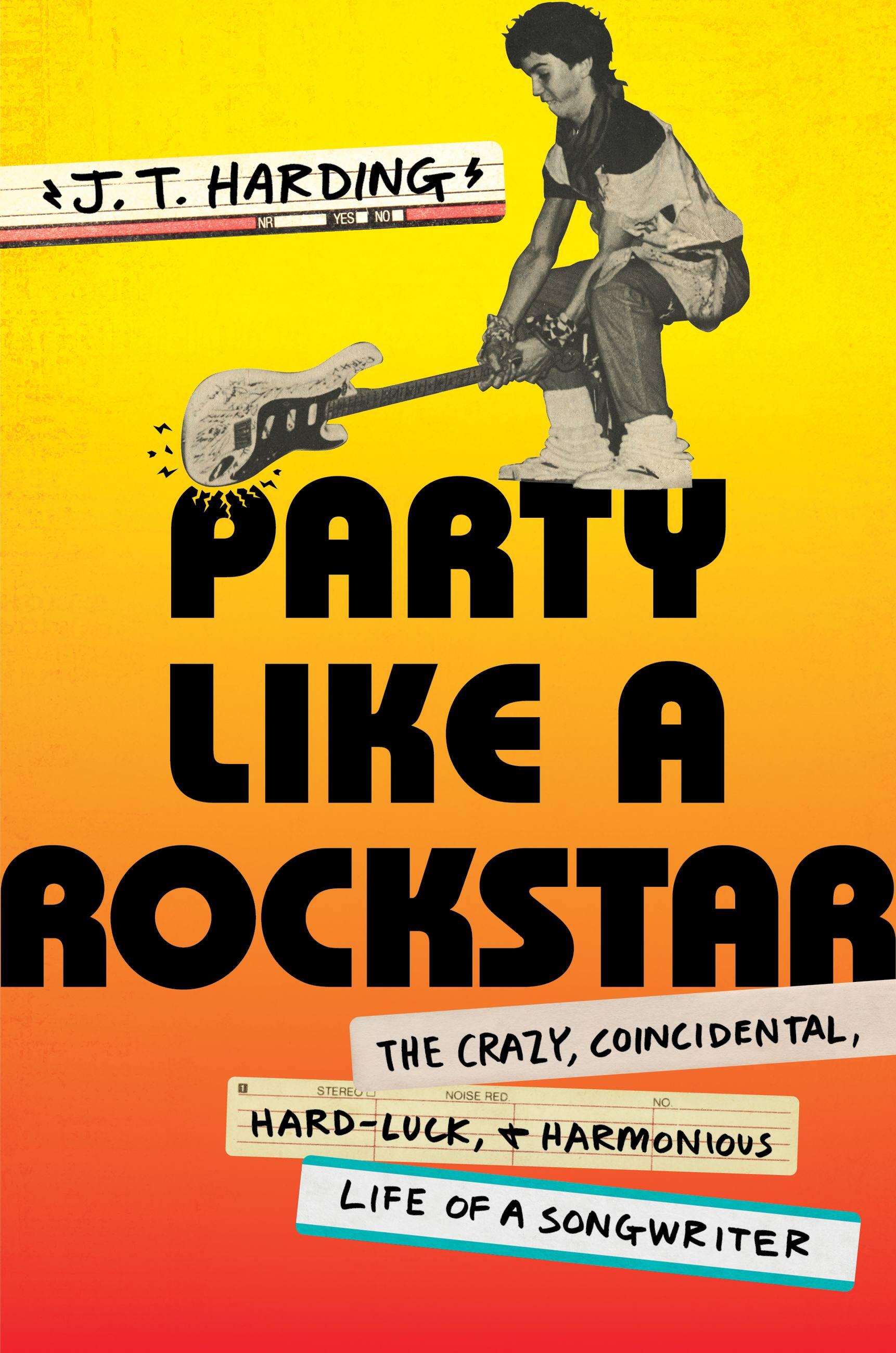

Party Like a Rockstar

The Crazy, Coincidental, Hard-Luck, and Harmonious Life of a Songwriter

Contributors

By J.T. Harding

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 22, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538735411

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 22, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR, J.T. Harding charts his life from a kid growing up in Michigan to a chart-topping songwriter living in Nashville and working with country music stars like Keith Urban and Kenny Chesney. As a kid playing rock n' roll in his parents' garage, Harding's was a world in which every taste of new music—from KISS to Prince and everyone in between—was a revelation. Inspired by his favorite artists, Harding abandons the classic "American Dream" and runs away to Los Angeles, where he forms a band and becomes part of the music scene there, all the while selling records to his favorite artists and producers at Tower Records.

A story of youth, rebellion, and determination, PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR is a memoir for music lovers and an invaluable how-to guide for anyone who wants to learn how to write a hit song. Fun and heartfelt, Harding's memoir is the story of one man's unshakable love for rock and roll, how it guided him through some of the greatest tragedies—and greatest triumphs—of his wild and unvarnished life.

-

"The stories behind J.T.'s songs are some of my favorites in music, but I didn't know his true backstory until now. It's surreal. His life is Forrest Gump meets Entourage. I laughed out loud, I Googled stuff to see if it was legit (it always was). I know what I'm getting everyone for their birthday this year: this book."TY Bentli, international country music expert and host of the "TY Bentli Show"

-

“You’ll definitely get great stories about songwriting from J.T. Harding—his heart gets broken more than the ice cream machine at McDonald’s.”Josh Osborne, Grammy award-winning songwriter

-

“What a great read! Super stories, like meeting Keith Urban in the men's room! Very moving family stuff. Every aspiring songwriter should read this for inspiration.”Jim Vallance, songwriter

-

“From the inventive chapter titles to the stories they contain—compelling true accounts of the incredible life of one of the most interesting people I’ve ever known, and one of the best songwriters of his generation—J.T. Harding’s PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR is one of the best memoirs I’ve ever read. Do yourself a favor and enjoy.”Bart Herbison, executive director, Nashville Songwriters Association International (NSAI)

-

“PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR may be a memoir, but it could just as easily be classified as a self-help book for those of us who struggle to be ourselves. J.T. Harding is the epitome of the American rock-n-roll dream and a true testament that anything is possible if you’re brave enough to dream it."Shane McAnally, three-time Grammy award-winning songwriter and star of NBC’s “Songland”

-

"I've loved J.T.'s stories since the first time I heard them at The Listening Room in Nashville. I knew that he would write a wonderful book. I love to be proven right. J.T. is a master storyteller—PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR reads like one of your very favorite songs. You can actually see and hear the scenes he writes. This is an American story of the unconditional love of parents, big dreams, hard work, and joy. His words become choruses that turn into chapters that write the story of his life so far, and I couldn’t put it down. I proudly recommend this book to readers or all ages. PARTY LIKE A ROCKSTAR is a hit!"Dana Perino, New York Times bestselling author of EVERYTHING WILL BE OKAY: Life Lessons for Young Women (From a Former Young Woman)

-

"As a songwriter, JT Harding knows how to tell a story. Turns out he has one of his own -- and quite a good, and moving, one at that. In a life filled with twist, turns and adventures, what shines through PARTY LIKE A ROCK STAR is Harding's genuine and consuming passion for music (and entertaining), a plus-size personality that's powered him to become a top-shelf collaborator responsible for so many hits we find ourselves humming at random times. The man behind those is every bit as interesting as the songs themselves, and you can't put this book down without wanting to party like a rock star a little yourself."Gary Graff, award-winning music journalist for MediaNews Group

-

"It’s a rare gift in terms of informing the recipient that writing songs is not a part-time thing. It’s a constant art that must be practiced and maintained every single day of the year.”Portland Book Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use