Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

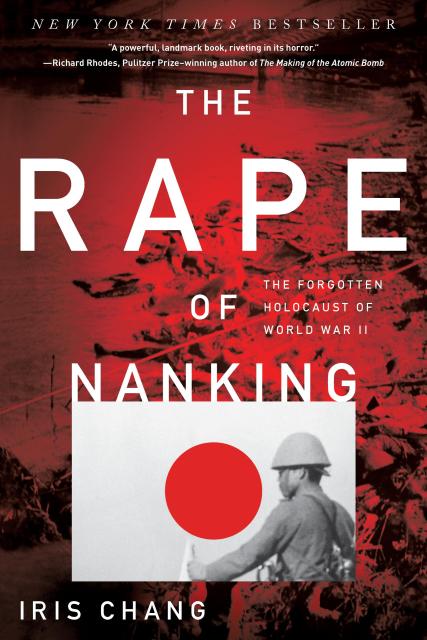

The Rape of Nanking

The Forgotten Holocaust Of World War II

Contributors

By Iris Chang

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 10, 2012

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465068364

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 10, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The New York Times bestselling account of one of history’s most brutal—and forgotten—massacres, when the Japanese army destroyed China’s capital city on the eve of World War II

“Chang vividly, methodically, records what happened, piecing together the abundant eyewitness reports into an undeniable tapestry of horror.” —Adam Hochschild, Salon

In December 1937, the Japanese army swept into the ancient city of Nanking. Within weeks, more than 300,000 Chinese civilians and soldiers were systematically raped, tortured, and murdered—a death toll exceeding that of the atomic blasts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. Historian Iris Chang tells the story from three perspectives: that of the Japanese soldiers, that of the Chinese, and that of a group of Westerners who refused to abandon the city and created a safety zone that saved almost 300,000 Chinese.

More than just narrating the details of an orgy of violence, in The Rape of Nanking Chang analyzes the militaristic culture that fostered in the Japanese soldiers a total disregard for human life. It also tells of the concerted effort during the Cold War on the part of the West and even China to stifle open discussion of this atrocity. Drawing on extensive interviews with survivors and documents brought to light for the first time, Iris Chang’s classic is the definitive history of this horrifying episode.

“Chang vividly, methodically, records what happened, piecing together the abundant eyewitness reports into an undeniable tapestry of horror.” —Adam Hochschild, Salon

In December 1937, the Japanese army swept into the ancient city of Nanking. Within weeks, more than 300,000 Chinese civilians and soldiers were systematically raped, tortured, and murdered—a death toll exceeding that of the atomic blasts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. Historian Iris Chang tells the story from three perspectives: that of the Japanese soldiers, that of the Chinese, and that of a group of Westerners who refused to abandon the city and created a safety zone that saved almost 300,000 Chinese.

More than just narrating the details of an orgy of violence, in The Rape of Nanking Chang analyzes the militaristic culture that fostered in the Japanese soldiers a total disregard for human life. It also tells of the concerted effort during the Cold War on the part of the West and even China to stifle open discussion of this atrocity. Drawing on extensive interviews with survivors and documents brought to light for the first time, Iris Chang’s classic is the definitive history of this horrifying episode.

Genre:

-

“A powerful, landmark book, riveting in its horror.”Richard Rhodes, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb

-

“The first comprehensive examination of the destruction of this Chinese imperial city… Ms. Chang, whose grandparents narrowly escaped the carnage, has skillfully excavated from oblivion the terrible events that took place.”Wall Street Journal

-

“In her important new book… Iris Chang, whose own grandparents were survivors, recounts the grisly massacre with understandable outrage.”Orville Schell, New York Times Book Review

-

“A powerful new work of history and moral inquiry. Chang takes great care to establish an accurate accounting of the dimensions of the violence.”Chicago Tribune

-

“Chang vividly, methodically, records what happened, piecing together the abundant eyewitness reports into an undeniable tapestry of horror.”Adam Hochschild, Salon

-

“The story that Chang tells is almost too appalling for words… a carefully documented cry of moral outrage.”Houston Chronicle

-

“Chang reminds us that however blinding the atrocities in Nanking may be, they are not forgettable—at least without peril to civilization itself.”Detroit News

-

“A compelling piece of history that speaks volumes about humankind’s inhumanity in the atrocities that have been documented and offers some vestiges of hope in the individual acts of heroism that also have been uncovered.”San Jose Mercury News

-

“A very readable, well‑organized account… Chang has rescued this episode from its undeserved obscurity.”Russell Jenkins, National Review

-

“Meticulously researched… A gripping account that holds the reader’s attention from beginning to end.”Nien Cheng, author of Life and Death in Shanghai

-

“Iris Chang’s research on the Nanking holocaust yields a new and expanded telling of this World War II atrocity and reflects thorough research. The book is excellent; its story deserves to be heard.”Beatrice S. Bartlett, professor of history, Yale University

-

“Heartbreaking… An utterly compelling book. The descriptions of the atrocities raise fundamental questions not only about imperial Japanese militarism but the psychology of the torturers, rapists, and murderers.”Frederic Wakeman, director of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley

-

“Something beautiful, an act of justice, is occurring in America today concerning something ugly that happened long ago… Because of Chang’s book, the second rape of Nanking is ending.”George F. Will, syndicated columnist

-

“Anyone interested in the relation between war, self‑righteousness, and the human spirit will find The Rape of Nanking of fundamental importance. It is scholarly, an exciting investigation, and a work of passion. In places it is almost unbearable to read, but it should be read only if the past is understood can the future be navigated.”Ross Terrill, author of Mao, China in Our Time, and Madame Mao

-

“One of the most important books of the twentieth century, Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking will endure as a classic among the world’s histories of war.”Nancy Tong, producer and co director of In the Name of the Emperor