By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

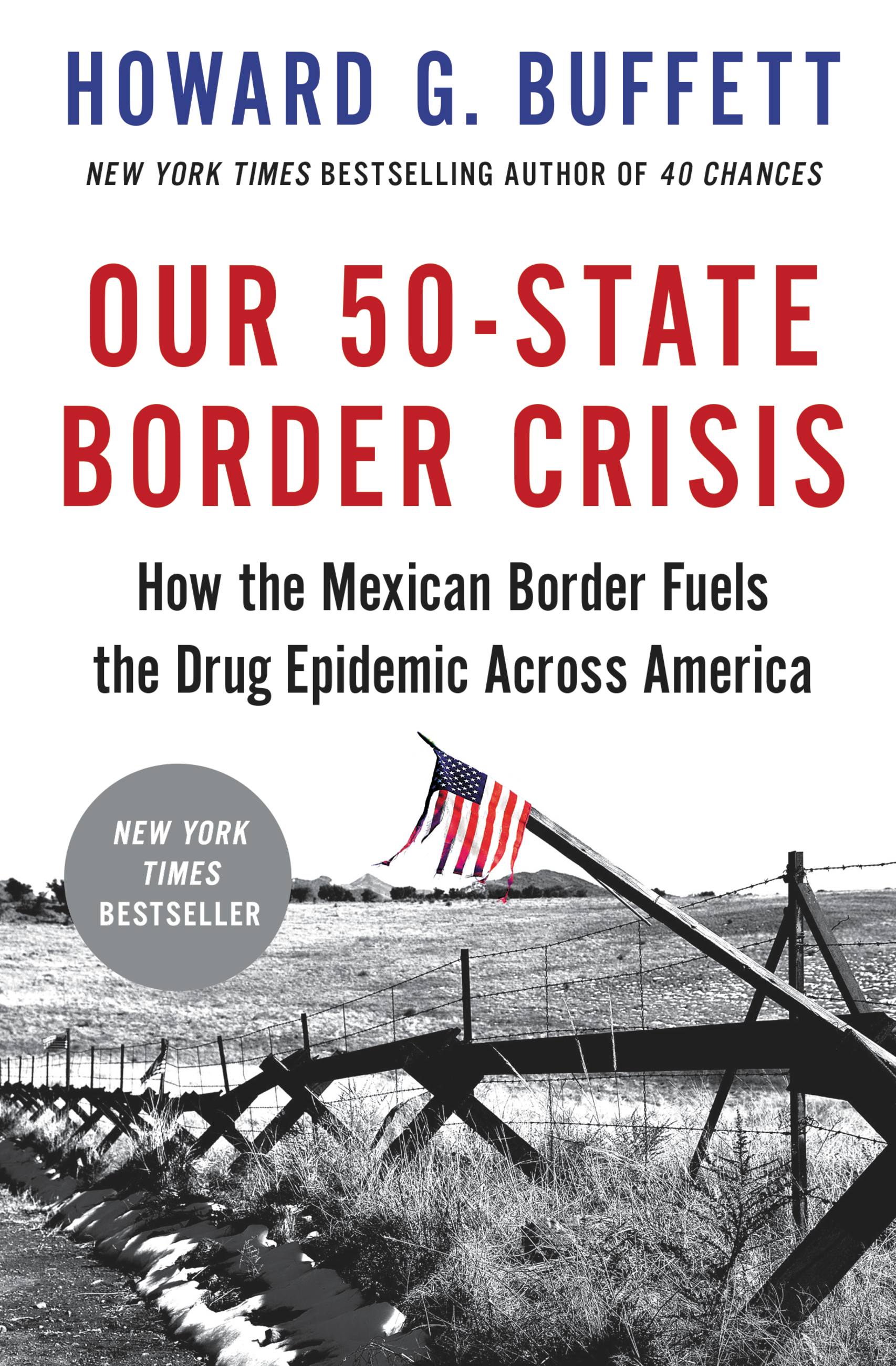

Our 50-State Border Crisis

How the Mexican Border Fuels the Drug Epidemic Across America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2019

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316476591

Price

$17.99Price

$23.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.49 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Howard G. Buffett has seen first-hand the devastating impact of cheap Mexican heroin and other opiate cocktails across America. Fueled by failing border policies and lawlessness in Mexico and Central America, drugs are pouring over the nation’s southern border in record quantities, turning Americans into addicts and migrants into drug mules — and killing us in record numbers.

Politicians talk about a border crisis and an opioid crisis as separate issues. To Buffett, a landowner on the U.S. border with Mexico and now a sheriff in Illinois, these are intimately connected. Ineffective border policies not only put residents in border states like Texas and Arizona in harm’s way, they put American lives in states like Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Vermont at risk.

Mexican cartels have grown astonishingly powerful by exploiting both the gaps in our border security strategy and the desperation of migrants — all while profiting enormously off America’s growing addiction to drugs. The solution isn’t a wall. In this groundbreaking book, Buffett outlines a realistic, effective, and bi-partisan approach to fighting cartels, strengthening our national security, and tackling the roots of the chaos below the border.

-

"[Buffett's] argument is not doctrinaire.... In all this, he urges probity and diplomacy... A useful, reasonable work of civilian policy analysis sure to invite discussion and even controversy."Kirkus

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use