By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

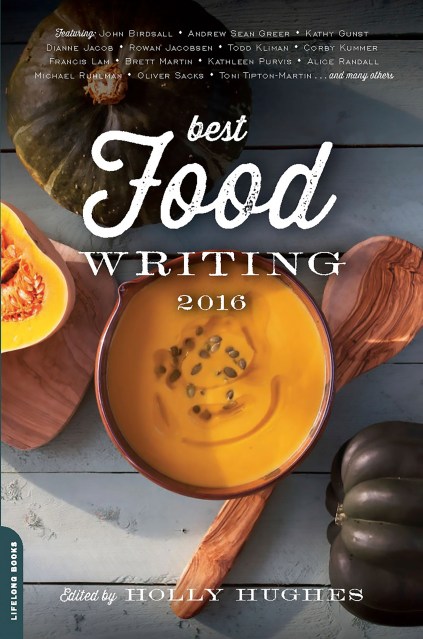

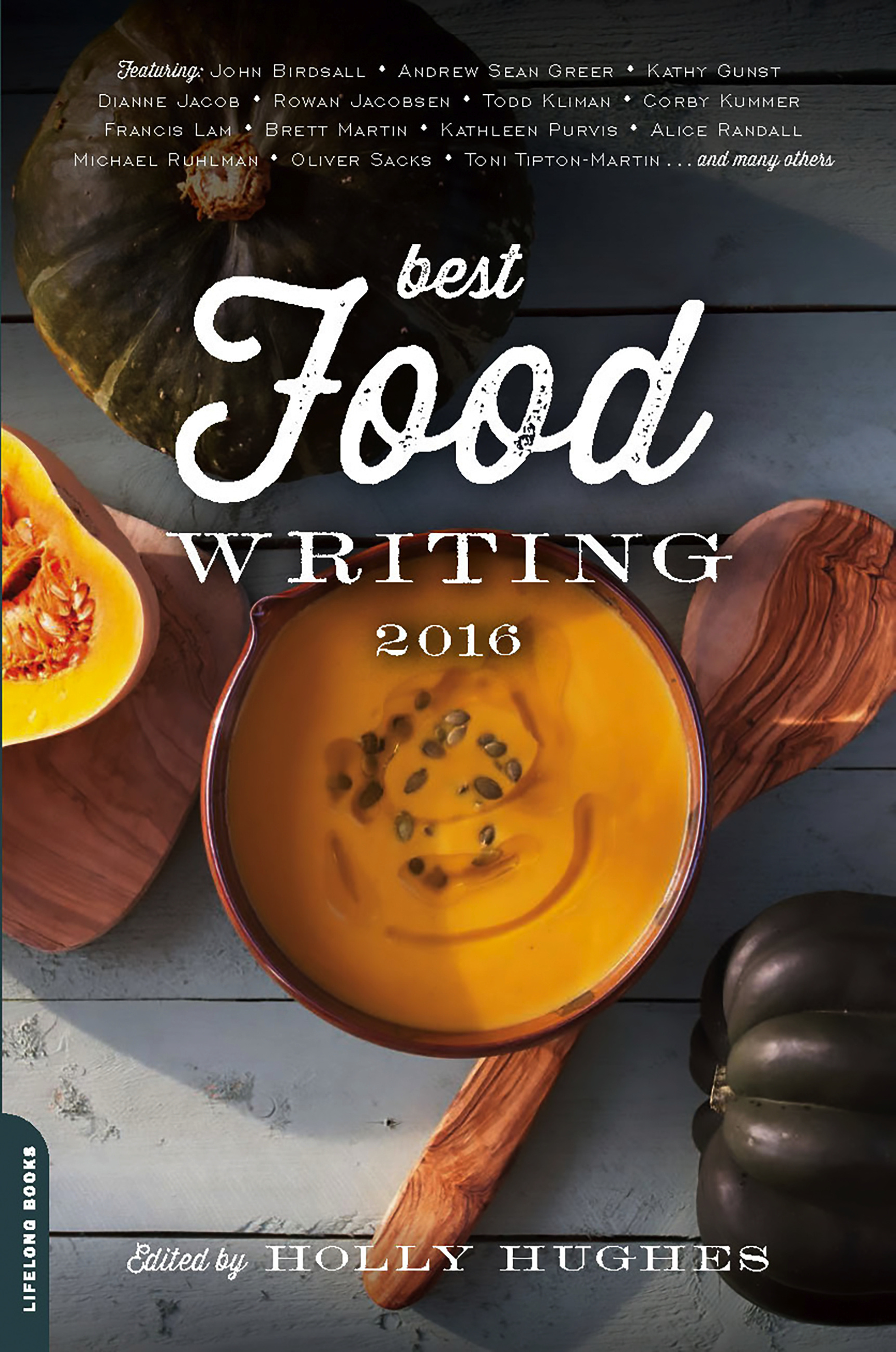

Best Food Writing 2016

Contributors

Edited by Holly Hughes

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 8, 2016

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780738219448

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 8, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Like your favorite local grocery store, with its sushi bar, fresh baked goods, and maybe a very obliging butcher, Best Food Writing offers a bounty of everything in one place. For seventeen years, Holly Hughes has delved into piles of magazines and newspapers, scanned endless websites and blogs, and foraged through bookstores to provide a robust mix of what’s up in the world of food writing. From the year’s hottest trends (this year: meal kits and extreme dining) to the realities of everyday meals and home cooks (with kids, without; special occasions and every day) to highlighting those chefs whose magic is best spun in their own kitchens, these essays once again skillfully, deliciously evoke what’s on our minds-and our plates. Pull up a chair.

Contributors include:

Betsy Andrews

Jessica Battilana

John Birdsall

Matt Buchanan

Jennifer Cockrall-King

Tove Danovich

Laura Donohue

Daniel Duane

Victoria Pesce Elliott

Edward Frame

Phyllis Grant

Andrew Sean Greer

Kathy Gunst

L. Kasimu Harris

Steve Hoffman

Dianne Jacob

Rowan Jacobsen

Pableaux Johnson

Howie Kahn

Mikki Kendall

Brian Kevin

Kat Kinsman

Todd Kliman

Julia Kramer

Corby Kummer

Francis Lam

Rachel Levin

Brett Martin

Tim Neville

Chris Newens

James Nolan

Keith Pandolfi

Carol Penn-Romine

Michael Procopio

Kathleen Purvis

Alice Randall

Besha Rodell

Helen Rosner

Michael Ruhlman

Oliver Sacks

Andrea Strong

Jason Tesauro

Toni Tipton-Martin

Wells Tower

Luke Tsai

Max Ufberg

Debbie Weingarten

Pete Wells

-

Praise for the Best Food Writing Series

“With this typically delectable and eclectic collection of culinary prose, editor Holly Hughes proves her point made in the intro that the death of 68-year-old Gourmet magazine a year ago didn't lead to the demise of quality food journalism…There's a mess of vital, provocative, funny and tender stuff…in these pages.”—USA Today

“Some of these stories can make you burn with a need to taste what they're writing about.”—Los Angeles Times

“The essays are thought-provoking and moving…This is an absolutely terrific and engaging book...There is enough variety, like a box of chocolates, that one can poke around the book looking for the one with caramel and find it.”—New York Journal of Books

“What is so great about this annual series is that editor Holly Hughes curates articles that likely never crossed your desk, even if you're an avid reader of food content. Nearly every piece selected is worth your time.”—The Huffington Post

“Stories for connoisseurs, celebrations of the specialized, the odd, or simply the excellent.”—Entertainment Weekly

“This book is a menu of delicious food, colorful characters, and tales of strange and wonderful food adventures that make for memorable meals and stories.”—Booklist

-

“This collection has something for connoisseurs, short story fans, and anyone hungry for a good read.”—Library Journal

“Browse, read a bit, browse some more and then head for the kitchen.”—Hudson Valley News

“The finest in culinary prose is offered in this new anthology…these pages delight and inform readers with entertaining and provocative essays…This book ultimately opens readers' eyes to honest, real food and the personal stories of the people behind it.”—Taste for Life

“Longtime editor Hughes once again compiles a tasty collection of culinary essays for those who love to eat, cook and read about food…A literary trek across the culinary landscape pairing bountiful delights with plenty of substantive tidbits.”—Kirkus Reviews

“A top-notch collection, Hughes brings together a wonderful mix that is sure to please the foodie in all of us.”—San Francisco Book Review

“An exceptional collection worth revisiting, this will be a surefire hit with epicureans and cooks.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“If you're looking to find new authors and voices about food, there's an abundance to chew on here.”—Tampa Tribune -

"There's something for everyone in the compilation, and because the stories are blog or magazine length, there's not much of a time commitment. If you only have 15 minutes to sit outdoors and read, you can finish at least one piece from beginning to end."Mother Nature Network

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use