Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

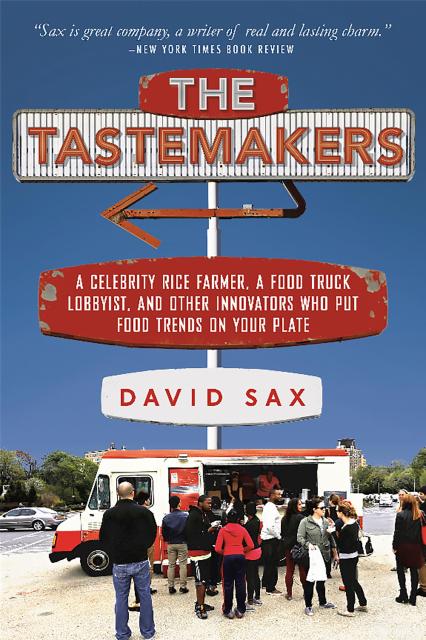

The Tastemakers

A Celebrity Rice Farmer, a Food Truck Lobbyist, and Other Innovators Putting Food Trends on Your Plate

Contributors

By David Sax

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 20, 2014

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393164

Price

$10.99Format

Format:

- Digital download $10.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 20, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A James Beard Award–winning journalist reveals the surprising forces that shape our eating habits

“Sax is great company, a writer of real and lasting charm.” —New York Times Book Review

In this eye-opening, witty work of reportage, David Sax uncovers the world of food trends: where they come from, how they grow, and where they end up. Traveling from the South Carolina rice plot of America’s premier grain guru to Chicago’s gluttonous Baconfest, Sax reveals a world of influence, money, and activism that helps decide what goes on your plate. On his journey, he meets entrepreneurs, chefs, and even data analysts who have made food trends a mission and a business. The Tastemakers is full of entertaining stories and surprising truths about what we eat, how we eat it, and why.

-

New York Times Book Review

“Entertaining . . . Sax has seized on a big, juicy topic, and is at his best in on-the-scene reporting, where the brisk, funny, assured voice that earned him many fans for his previous book, keeps us galloping through the aisles . . . Sax is great company, a writer of real and lasting charm. . . . The Tastemakers will leave readers wondering about how susceptible we are to the charms of any new food—and how long we’re likely to stay captivated.”

-

The Economist

“[Sax] embarks on a lively culinary your of America, consulting chefs, producers, foodies, food buyers, and trend forecasters to find out why one day sriracha sauce is all the rage, and the next, people are adding kale to every meal.”

-

Toronto Star

“[Sax’s] portraits of the food evangelists at the root of some trends are highly entertaining and, in addition, it’s hard to imagine anyone else who could trace the provenance of the cupcake as thoroughly and comprehensively as Sax.”

-

LA Weekly

“Amusing and informative . . . The Tastemakers delves into food trends from various angles, like the importance of money, food politics and marketing.”

-

The Globe and Mail

“Sax's book is enjoyably in-depth compared to today’s fast-paced world of food-trend reporting.”

-

A. J. Jacobs, New York Times bestselling author of The Year of Living Biblically

“Sax has written a fascinating and surprising story of why we eat what we eat. It’s a tale of overhyped chia seeds, rebranded fish, and unseen influencers. I will never again look at a grocery store aisle or my restaurant entree the same way.”

-

David Kamp, author of The United States of Arugula

“With forensic specificity, and, better still, a terrific sense of fun, David Sax explains precisely how foods du jour such as cupcakes, Greek yogurt, and Korean tacos ‘happened.’ The trends may seem silly, but The Tastemakers is not. Sax has given this gastro-exuberant time the whizzy, full-gallop treatment it deserves.”

-

Karen Leibowitz, coauthor of Mission Street Food

“They say there’s no accounting for taste, but David Sax makes sense of the mysterious forces that shape our personal food preferences, through stories so absorbing and witty that I wasn’t even sorry to discover that my taste buds are hardly my own. I devoured The Tastemakers like an oat bran muffin in 1989—or a chia-seed muffin today.”

-

Kirkus

“Sax has done his homework—and probably put on a few pounds. A solid overview of trendsetting foods brought to life with colorful examples.”

-

Publishers Weekly

“Sax declares, food trends, though sometimes annoying, deepen and expand our cultural palate, spur economic growth, provide broad variety in our diets, and promote happiness.”