Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

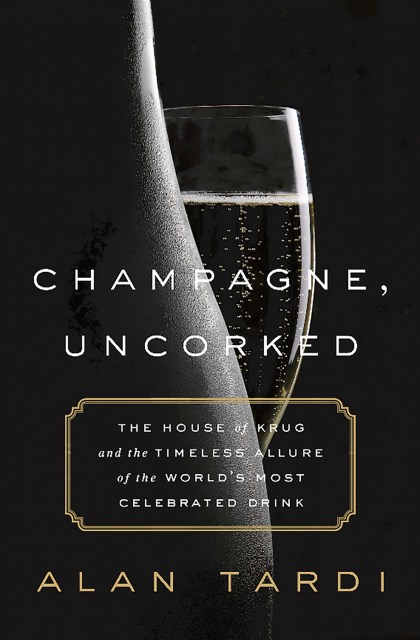

Champagne, Uncorked

The House of Krug and the Timeless Allure of the World’s Most Celebrated Drink

Contributors

By Alan Tardi

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 24, 2016

- Page Count

- 296 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610396882

Price

$26.99Price

$34.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $26.99 $34.99 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 24, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Champagne, Uncorked, Alan Tardi journeys into the heartland of the world’s most beloved wine. Anchored by the year he spent inside the prestigious and secretive Krug winery in Reims, the story follows the creation of the superlative Krug Grande Cuv’e.

Tardi also investigates the evocative history, quirky origins, and cultural significance of Champagne. He reveals how it became the essential celebratory toast (merci Napoleon Bonaparte!), and introduces a cast of colorful characters, including Eugè Mercier, who in 1889 transported his “Cathedral of Champagne,” the largest wine cask in the world, to Paris by a team of white horses and oxen, and Joseph Krug, the reserved son of a German butcher who wound up in France, fell head over heels for Champagne, and risked everything to start up his own eponymous house.

In the vineyards of Champagne, Tardi discovers how finicky grapes in an unstable climate can lead to a nerve-racking season for growers and winemakers alike. And he ventures deep into the caves, where the delicate and painstaking alchemy of blending takes place — all of which culminates in the glass we raise to toast life’s finer moments.

-

“Champagne, Uncorked is a page-turner that offers up the wine's history, the characters who made it and, with appealing intimacy, those of the House of Krug from top to bottom. It is a must read for any Champagne lover and of course for ‘Krugistes.'” —Stephen Spurrier, consulting editor of Decanter

“A fascinating account of the making of one of the world's great wines, and one that will thrill both novice and connoisseur alike. This is one of the best books to ever be written about champagne, and it should be on the reading list of anyone interested in wine.” —Peter Liem, senior correspondent for Wine & Spirits and founder of Champagneguide.net

“Alan Tardi's background as a restaurateur, chef, and wine writer makes him uniquely qualified to write this exceptional book on Champagne. Throughout, he integrates the history of Champagne, the making of Champagne, along with the production of Krug's Grande Cuvée, one of the world's greatest Champagnes. Alan is a truly gifted writer, not only teaching us, but weaving a story that is fascinating and illuminating.” —Ed McCarthy, author of Champagne For Dummies -

“The fascinating story of the most loved wine.” —The Washington Book Review

“Tardi chronicles his time following a tense year in the life cycle of champagne, from harvest to bottling, at the renowned Krug house, expertly balancing his personal experiences with extensive historical research of the development and sophistication of champagne as well as the establishment of the Krug winery. Part memoir and part history, Tardi's love letter to champagne can inspire the reader to delve deeper into viticulture.” —Booklist, Starred Review

“Champagne, Uncorked packs an enormous amount of detail and complexity (historical, chemical, biological, emotional) into a rather small package—a fitting tribute to the nuance and complexity found in every glass of champagne Krug has produced…A fascinating and detailed history.” —Shelf Awareness

“An unprecedented look into the process of crushing grapes, fermenting, tasting, blending, bottling, and aging that leads to the Krug Grande Cuvée, one of the most prestigious non-vintage champagnes on the market…Compelling and interesting…[Champagne, Uncorked] carries a wealth of information for a reader at any level of wine expertise.” —Publishers Weekly -

“Knowledgeable and meticulously researched…[Tardi] takes the reader through the whole process, from picking and pressing the grapes—the vendange—through the storing, tasting and blending of the wine to its bottling and aging…A colorful history of Champagne.” –Moira Hodgson, Wall Street Journal

“Sparkles with information about the beverage of celebration and specifically the making of Krug Grande Cuvee, a great Champagne from arguably the greatest producer. History, harvesting, tasting, blending, marketing, presented with easy going style. You'll want to make a pilgrimage to Le Mesnil-sur-Oger.” –Peter Gianotti, Newsday

“In Tardi's fabulous new book, he explains the history of the Champagne region and why the land produces the grapes it does…while weaving together a rich cultural overview of the sparkling elixir's wild rise to becoming the world's symbol of celebration. When people try [Krug] for the first time, they talk about it effusively like love-struck Romeos. Don't believe me? Try it for yourself. But first read Tardi's book.” —San Antonio Express-News

“A book as effervescent and fascinating as the product it describes. Readers gain insight into a world as complex as the blending of a fine bottle of Champagne.” —Galveston County Daily News