Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

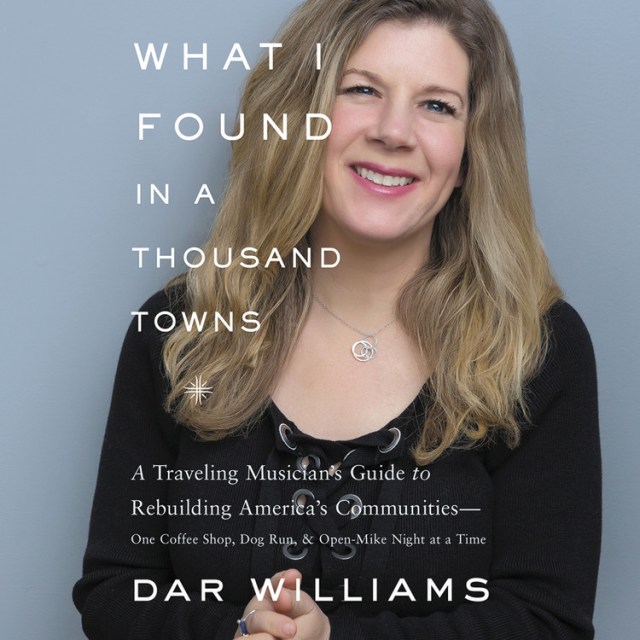

What I Found in a Thousand Towns

A Traveling Musician's Guide to Rebuilding America's Communities-One Coffee Shop, Dog Run, and Open-Mike Night at a Time

Contributors

By Dar Williams

Read by Dar Williams

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2017

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478923534

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Dubbed by the New Yorker as “one of America’s very best singer-songwriters,” Dar Williams has made her career not in stadiums, but touring America’s small towns. She has played their venues, composed in their coffee shops, and drunk in their bars. She has seen these communities struggle, but also seen them thrive in the face of postindustrial identity crises.

Here, in an account that “reads as if Pete Seeger and Jane Jacobs teamed up” (New York Times), Williams muses on why some towns flourish while others fail, examining elements from the significance of history and nature to the uniting power of public spaces and food. Drawing on her own travels and the work of urban theorists, Williams offers real solutions to rebuild declining communities.

What I Found in a Thousand Towns is more than a love letter to America’s small towns, it’s a deeply personal and hopeful message about the potential of America’s lively and resilient communities.