By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

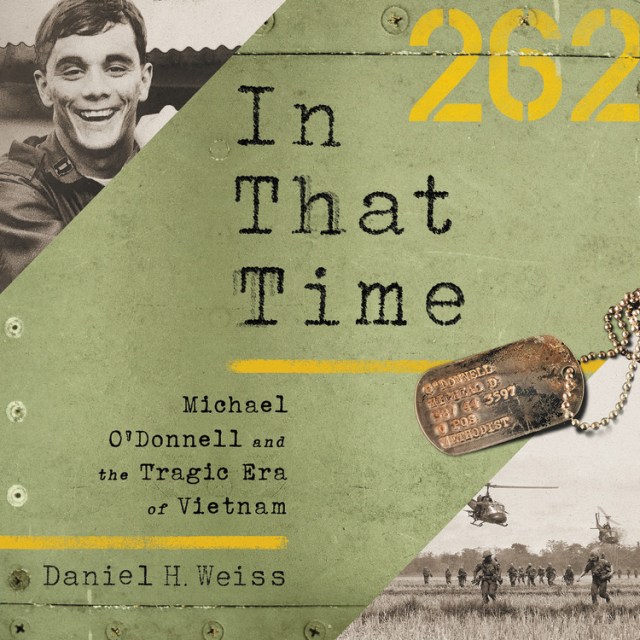

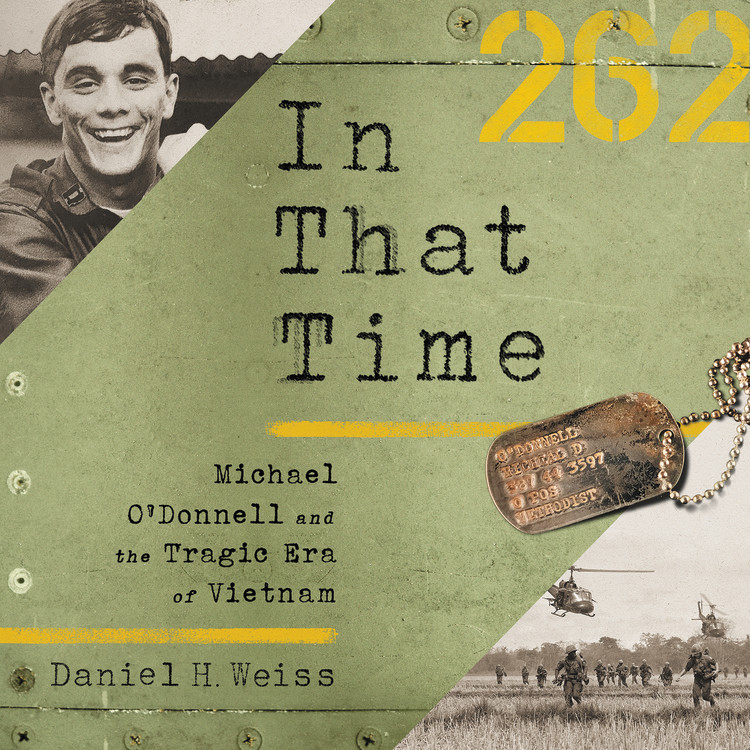

In That Time

Michael O'Donnell and the Tragic Era of Vietnam

Contributors

Read by Daniel H. Weiss

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549152689

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.00 $33.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Through the story of the brief, brave life of a promising poet, the president and CEO of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art evokes the turmoil and tragedy of the Vietnam War era.

In That Time tells the story of the American experience in Vietnam through the life of Michael O’Donnell, a bright young musician and poet who served as a soldier and helicopter pilot. O’Donnell wrote with great sensitivity and poetic force, and his best-known poem is among the most beloved of the war. In 1970, during an attempt to rescue fellow soldiers stranded under heavy fire, O’Donnell’s helicopter was shot down in the jungles of Cambodia. He remained missing in action for almost three decades.

Although he never fired a shot in Vietnam, O’Donnell served in one of the most dangerous roles of the war, all the while using poetry to express his inner feelings and to reflect on the tragedy that was unfolding around him. O’Donnell’s life is both a powerful, personal story and a compelling, universal one about how America lost its way in the 1960s, but also how hope can flower in the margins of even the darkest chapters of the American story.

In That Time tells the story of the American experience in Vietnam through the life of Michael O’Donnell, a bright young musician and poet who served as a soldier and helicopter pilot. O’Donnell wrote with great sensitivity and poetic force, and his best-known poem is among the most beloved of the war. In 1970, during an attempt to rescue fellow soldiers stranded under heavy fire, O’Donnell’s helicopter was shot down in the jungles of Cambodia. He remained missing in action for almost three decades.

Although he never fired a shot in Vietnam, O’Donnell served in one of the most dangerous roles of the war, all the while using poetry to express his inner feelings and to reflect on the tragedy that was unfolding around him. O’Donnell’s life is both a powerful, personal story and a compelling, universal one about how America lost its way in the 1960s, but also how hope can flower in the margins of even the darkest chapters of the American story.

-

"Poignant...Weiss brilliantly evokes O'Donnell's fatal mission and the toll his MIA status took on his loved ones...As a précis on the tragic place Vietnam holds in the American consciousness... this slim book succeeds admirably."Publishers Weekly

-

"a stunning book... well written and presented. Weiss, the president and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is an accomplished researcher and writer. He has produced a nicely constructed offering that threads a historical narrative of the Vietnam War into the story of Army Capt. Michael D. O'Donnell...I enjoyed this book. I recommend that it become a staple in high school curricula as a resource during the study of the Vietnam War."VVA Veteran

-

"So many years after the Vietnam War, Dan Weiss has written an elegiac book about a soldier and poet who died when his helicopter went down in the jungle. A tribute to all soldiers who died in Vietnam, it's also a reminder that soldiers die at the will of people who may or may not understand what they are sending them to die for."Frances Fitzgerald, author of Fire in the Lake

-

"This is a brilliant reflective recreation of Michael O'Donnell's Vietnam and the insistent questions in his sacrifice."Harold Evans, author of The American Century

-

"They called it the pucker factor--the helplessness you felt riding in a chopper taking fire from below. It took half a century to dull those memories. Dan Weiss brought them back in one chapter."James Sterba, Vietnam correspondent, New York Times, 1969-1970

-

"Dan Weiss has told a compelling story about the creative and artistic spirit of one soldier, but learning about Michael O'Donnell forces us to remember that there were more than 58,000 such stories of lives cut short; wives, parents, and siblings left behind; children unborn; songs not sung; and poems not written. Each of these deaths is like a jagged scar on the soul of our nation, made all the more infuriating for having occurred as part of a poorly explained and inconclusive war. In That Time reminds us what happens when leaders fail, that at the end of every bullet is someone's son or daughter, someone like Michael O'Donnell."William S. Cohen, secretary of defense, 1997-2001

-

"In That Time rescues a young man's life from the jungle ravine where his helicopter crashed during the Vietnam War and was left undiscovered for decades. Like thousands of other soldiers whose lives had barely begun only to be squandered in that war, Michael O'Donnell had his hopes and dreams, family and friends. His poems about the war are still shared by veterans. Weiss examines O'Donnell's loss with meticulous and civic compassion."John Balaban, author of Remembering Heaven's Face

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use