By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

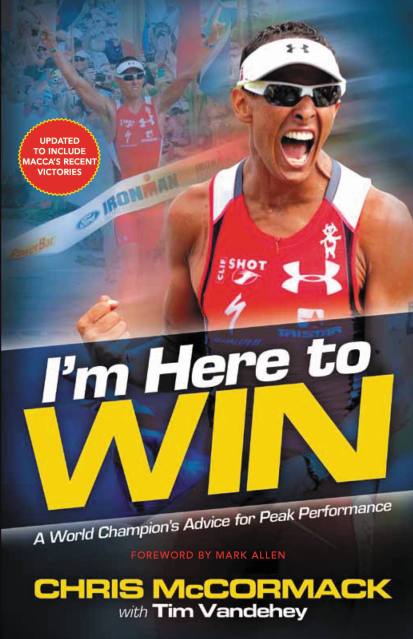

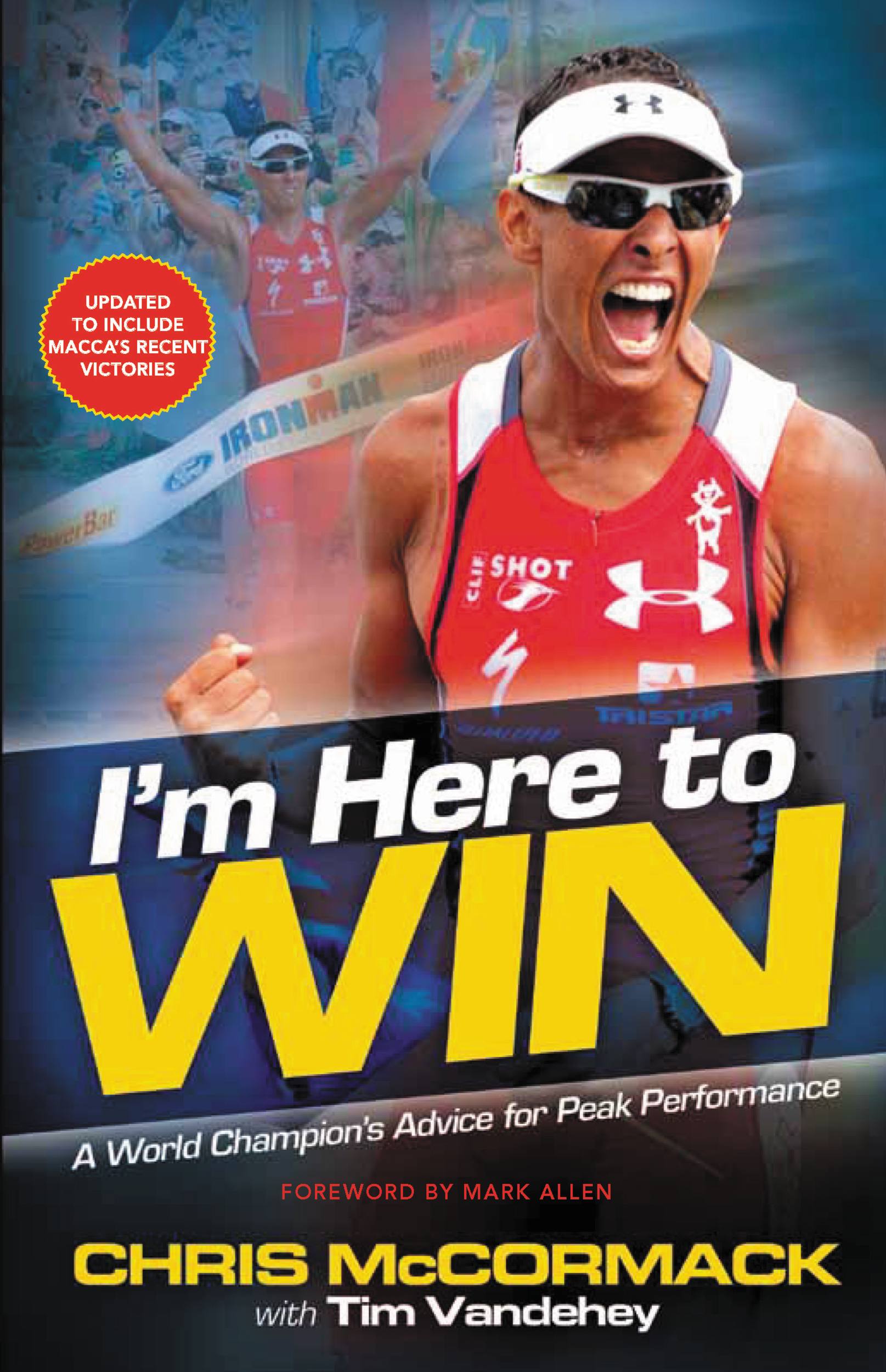

I’m Here To Win

A World Champion's Advice for Peak Performance

Contributors

With Tim Vandehey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 23, 2011

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781455502660

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 23, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In I’M HERE TO WIN, Chris “Macca” McCormack opens his playbook and reveals everything it takes-mind, body, and spirit-to become a champion. Now he shares the story of his triumphs and the never-say-die dedication that has made him the world’s most successful triathlete.

In 2010, at the age of 37, Macca beat the odds and won the Ford Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii for a second time in what many called the most dramatic finish in the race’s history. Macca’s journey to athletic greatness is more than just one of physical perseverance. After coming in fourth in Hawaii in 2009, Macca returned to the island on a mission: He was there to win. A game plan containing a new strategic approach to winning brought him first across the finish line.

Chris McCormack has dedicated his life to training for-and winning-the Ironman Hawaii, one of the most grueling tests of mental and physical endurance in the world. The race challenges athletes to swim 2.4 miles, bike 112 miles, and run a full marathon, 26.2 miles, using all their strength and willpower to overcome the incredibly harsh conditions.

In I’M HERE TO WIN Macca provides concrete training advice for everyone-from weekend warriors who casually compete to seasoned veterans who race every week to armchair athletes looking for an extra push-and provides insight into the mind of a great champion with excitement and inspiration on every page.

I’M HERE TO WIN is also available as an enhanced e-book with embedded video and audio.

In 2010, at the age of 37, Macca beat the odds and won the Ford Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii for a second time in what many called the most dramatic finish in the race’s history. Macca’s journey to athletic greatness is more than just one of physical perseverance. After coming in fourth in Hawaii in 2009, Macca returned to the island on a mission: He was there to win. A game plan containing a new strategic approach to winning brought him first across the finish line.

Chris McCormack has dedicated his life to training for-and winning-the Ironman Hawaii, one of the most grueling tests of mental and physical endurance in the world. The race challenges athletes to swim 2.4 miles, bike 112 miles, and run a full marathon, 26.2 miles, using all their strength and willpower to overcome the incredibly harsh conditions.

In I’M HERE TO WIN Macca provides concrete training advice for everyone-from weekend warriors who casually compete to seasoned veterans who race every week to armchair athletes looking for an extra push-and provides insight into the mind of a great champion with excitement and inspiration on every page.

I’M HERE TO WIN is also available as an enhanced e-book with embedded video and audio.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use