By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

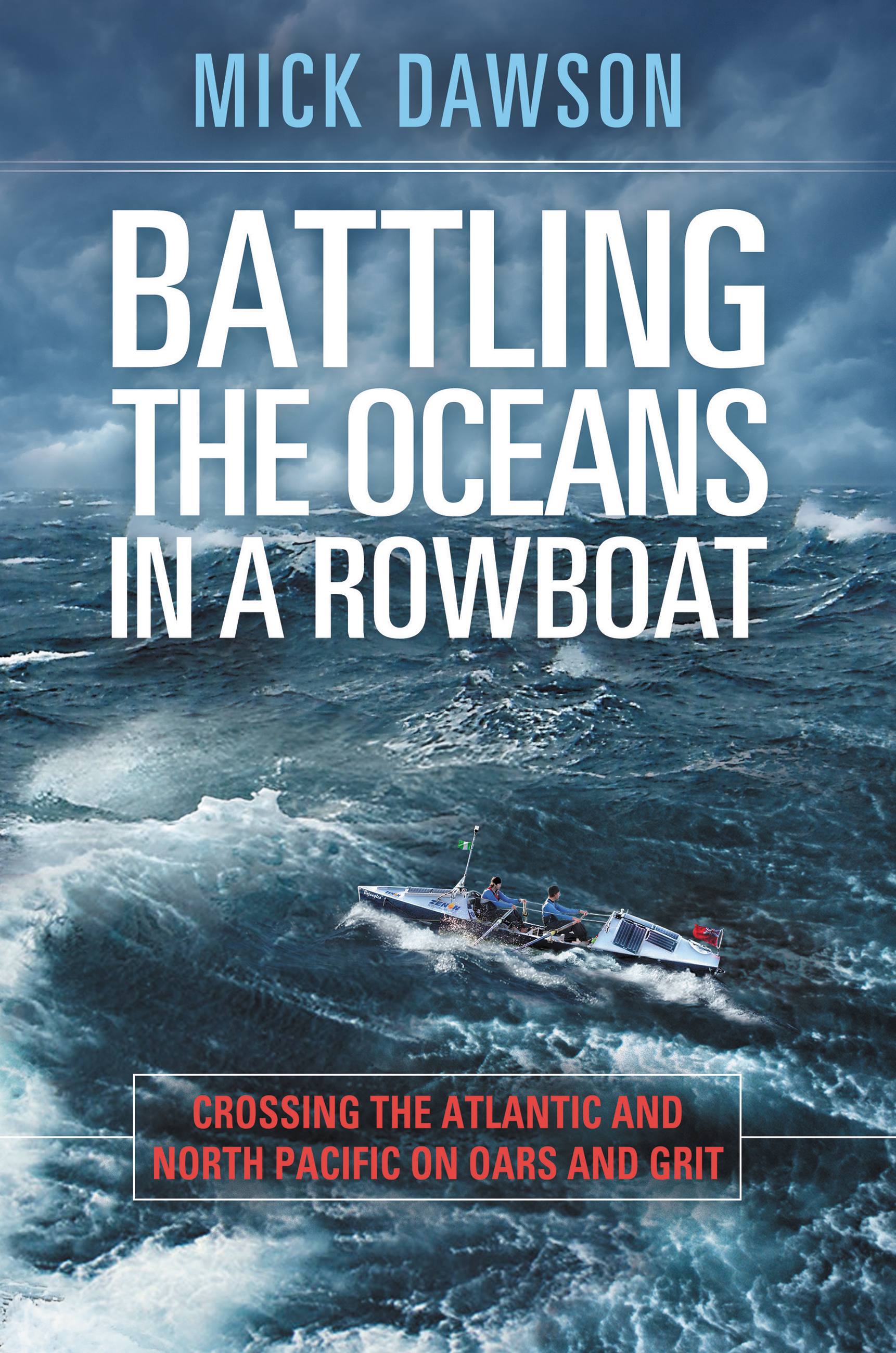

Battling the Oceans in a Rowboat

Crossing the Atlantic and North Pacific on Oars and Grit

Contributors

By Mick Dawson

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 22, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781478947523

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 22, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The heart-pounding story of rowing expert Mick Dawson’s most challenging feats on the open water, culminating in his greatest achievement: crossing the North Pacific Ocean in a small rowboat.

Storms, fatigue, equipment failure, intense hunger, and lack of water are just a few of the challenges that ocean rower MICK DAWSON, endured whilst attempting to complete one of the World’s “Last Great Firsts.”

In this nail-biting, man-against-nature true story, Dawson, former Royal Marine Commando, Guinness world record ocean rower and high seas adventurer, takes on the Atlantic and ultimately the North Pacific Oceans.

It would require three attempts and a back breaking voyage of over six months to finally cross the mighty North Pacific for the first time. 189 days, 10 hours and 55 minutes rowing around the clock, fighting death and destruction every step of the way before finally arriving beneath the iconic span of the Golden Gate Bridge with his friend and rowing partner Chris Martin.

Dawson details his epic adventures propelling his tiny boat one stroke at a time for thousands of miles across the most hostile route of the greatest ocean on earth, overcoming failure, personal tragedy and all of the challenges mother nature could throw at him.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use