By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

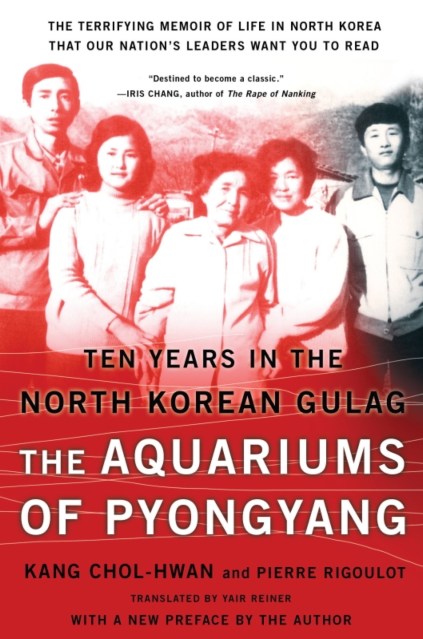

The Aquariums of Pyongyang

Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 24, 2005

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465004713

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 24, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Amid escalating nuclear tensions, Kim Jong-un and North Korea’s other leaders have kept a tight grasp on their one-party state, quashing any nascent opposition movements and sending all suspected dissidents to its brutal concentration camps for “re-education.”

Kang Chol-Hwan is the first survivor of one of these camps to escape and tell his story to the world, documenting the extreme conditions in these gulags and providing a personal insight into life in North Korea. Sent to the notorious labor camp Yodok when he was nine years old, Kang observed frequent public executions and endured forced labor and near-starvation rations for ten years. In 1992, he escaped to South Korea, where he found God and now advocates for human rights in North Korea.

Part horror story, part historical document, part memoir, part political tract, this book brings together unassailable firsthand experience, setting one young man’s personal suffering in the wider context of modern history, giving eyewitness proof to the abuses perpetrated by the North Korean regime.

Genre:

-

"The Aquariums of Pyongyang is one of the most terrifying memoirs I have ever read. As the first account to emerge from North Korea, it is destined to become a classic."Iris Chang, authorof The Rape of Nanking

-

"A triumph against silence."Financial Times

-

"A chilling testimony.... Freezes the heart and seizes the soul."Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use