By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

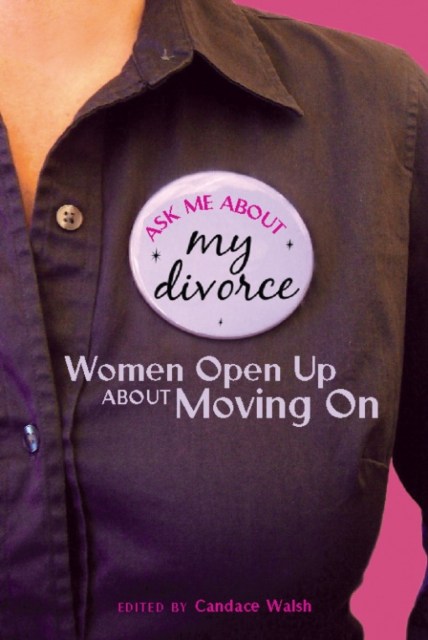

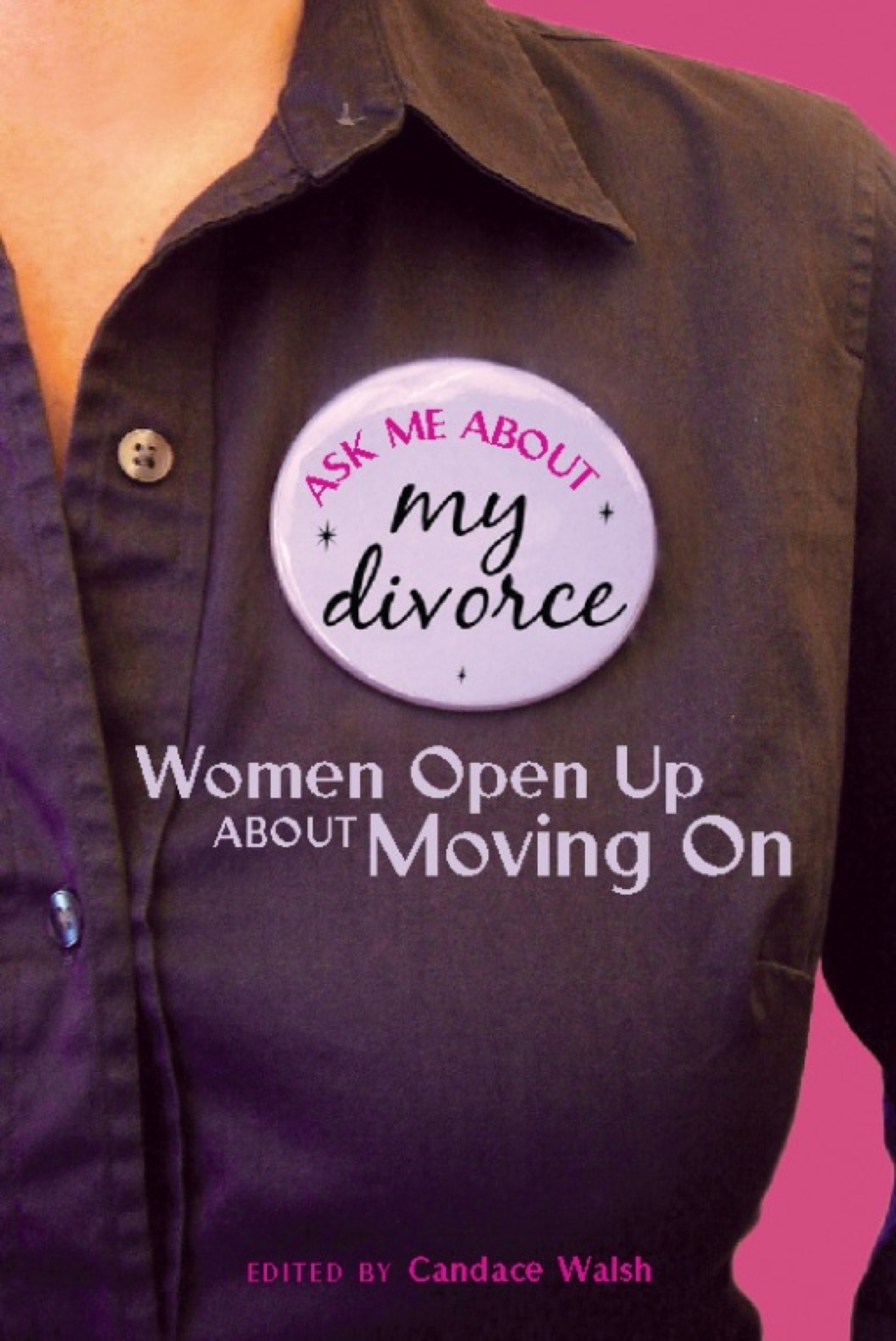

Ask Me About My Divorce

Women Open Up About Moving On

Contributors

Edited by Candace Walsh

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 21, 2009

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786744817

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 21, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It’s time to get past the idea that divorce equals failure. Sure, it may not be what you had in mind when you walked down the aisle, but if it’s the escape hatch into a better life, it should be filled with more promise. It can be celebrated.

Ask Me About My Divorce is a spicy, fun, riveting collection of essays by women from all walks of life. With the unifying thread "I got divorced, and the world came into view," the words within will make readers laugh, cry, nod their heads, and feel inspired to do what they need to for themselves. These aren't stories from women tiptoeing around a difficult subject—they're about the ways divorce can be, in fact, a new lease on life.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use