By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

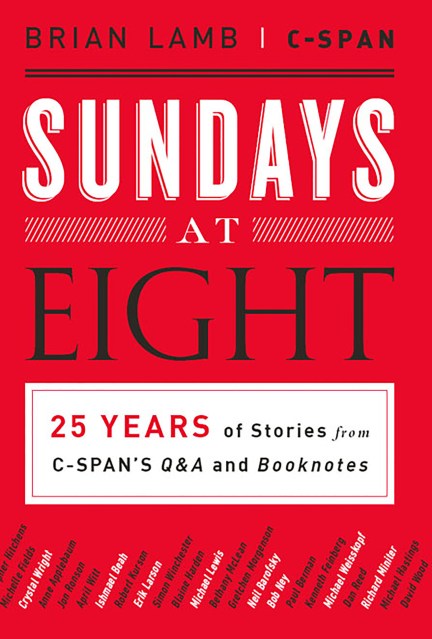

Sundays at Eight

25 Years of Stories from C-SPAN'S Q&A and Booknotes

Contributors

By Brian Lamb

By C-SPAN

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 29, 2014

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610393492

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $44.00 $55.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 29, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

First came C-SPAN’s Booknotes in 1989, which by the time it ended in December 2004, was the longest-running author-interview program in American broadcast history. Many of the most notable nonfiction authors of its era were featured over the course of 800 episodes, and the conversations became a defining hour for the network and for nonfiction writers.

In January 2005, C-SPAN embarked on a new chapter with the launch of Q and A. Again one hour of uninterrupted conversation but the focus was expanded to include documentary film makers, entrepreneurs, social workers, political leaders and just about anyone with a story to tell.

To mark this anniversary Lamb and his team at C-SPAN have assembled Sundays at Eight, a collection of the best unpublished interviews and stories from the last 25 years. Featured in this collection are historians like David McCullough, Ron Chernow and Robert Caro, reporters including April Witt, John Burns and Michael Weisskopf, and numerous others, including Christopher Hitchens, Brit Hume and Kenneth Feinberg.

In a March 2001 Booknotes interview 60 Minutes creator Don Hewitt described the show’s success this way: “All you have to do is tell me a story.” This collection attests to the success of that principle, which has guided Lamb for decades. And his guests have not disappointed, from the dramatic escape of a lifelong resident of a North Korean prison camp, to the heavy price paid by one successful West Virginia businessman when he won 314 million in the lottery, or the heroic stories of recovery from the most horrific injuries in modern-day warfare. Told in the series’ signature conversational manner, these stories come to life again on the page. Sundays at Eight is not merely a token for fans of C-SPAN’s interview programs, but a collection of significant stories that have helped us understand the world for a quarter-century.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use