By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

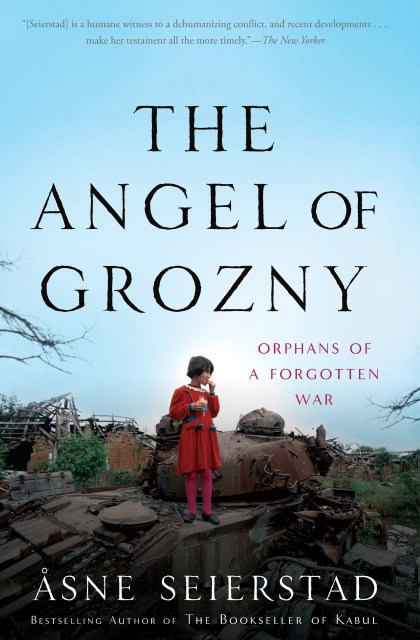

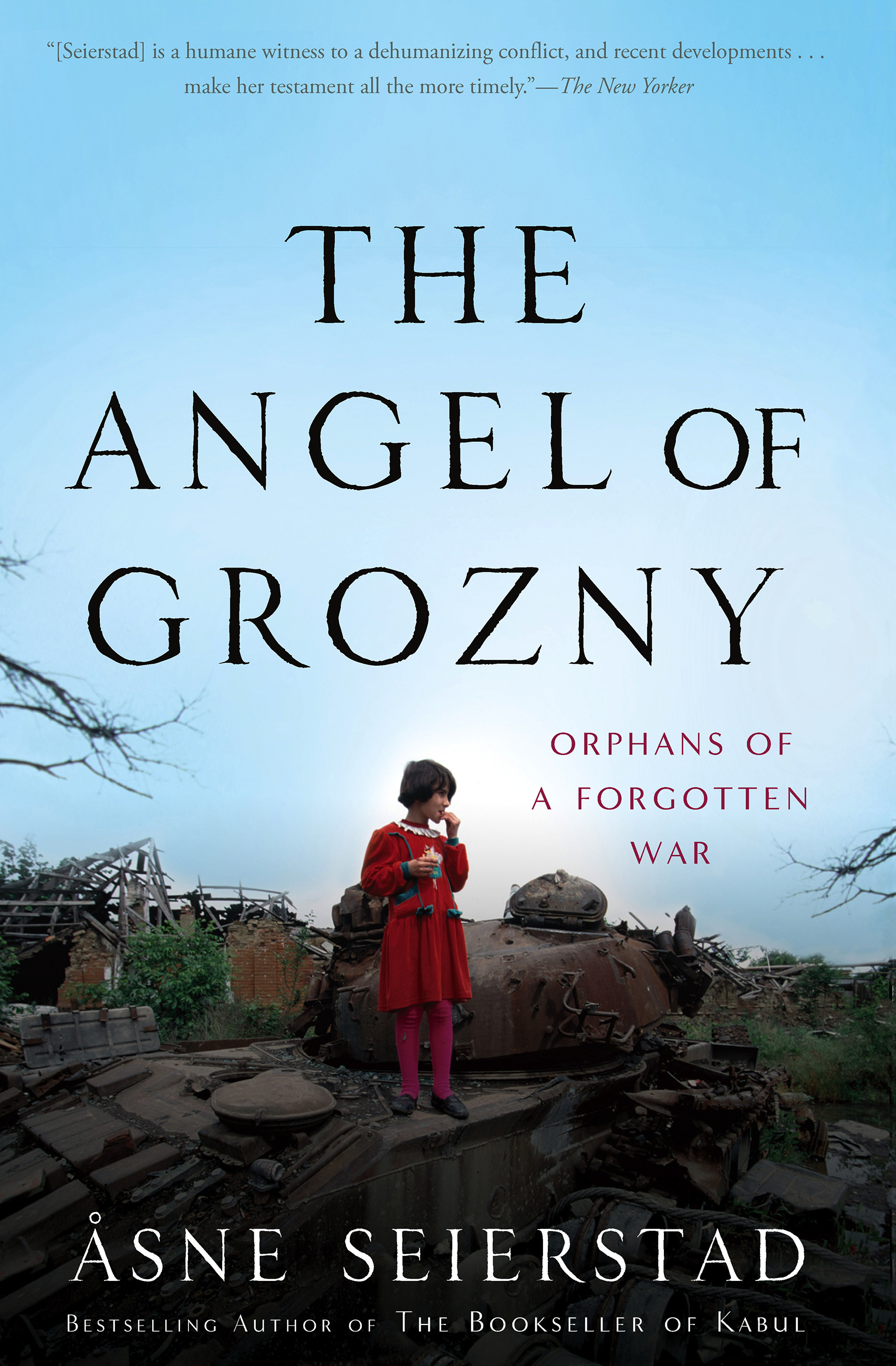

The Angel of Grozny

Orphans of a Forgotten War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 25, 2010

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465019496

Price

$22.99Price

$29.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 25, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the following decade, Seierstad became an internationally renowned reporter and author, traveling to the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, and other war-torn regions. But she never lost sight of this conflict that had initially inspired her career. Over the course of a decade, she watched as Russia ruthlessly suppressed an Islamic rebellion in two bloody wars and as Chechnya evolved into one of the flashpoints in a world now focused on the threat of international terrorism.

In 2006, Seierstad finally returned to Chechnya, traveling in secret and under the constant threat of danger. In a broken and devastated society she lived with orphans, the wounded, the lost. And she lived with the children of Grozny, those who will shape the country’s future. She asks the question: What happens to a child who grows up surrounded by war and accustomed to violence?

A compelling, intimate, and often heartbreaking portrait of Chechnya today, The Angel of Grozny is a vivid account of a land’s violent history and its ongoing battle for freedom.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use