By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

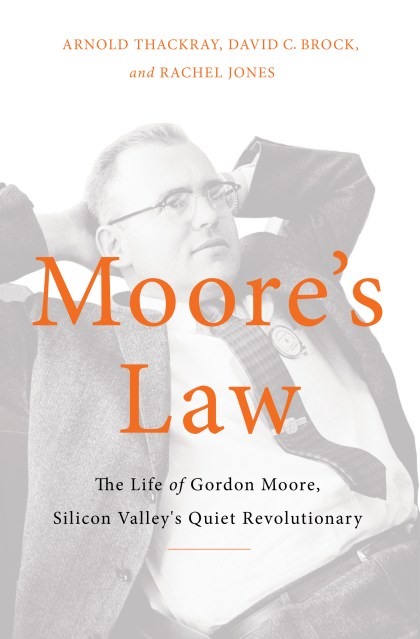

Moore’s Law

The Life of Gordon Moore, Silicon Valley's Quiet Revolutionary

Contributors

By David C. Brock

By Rachel Jones

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 5, 2015

- Page Count

- 560 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465055623

Price

$23.99Price

$30.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $23.99 $30.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $43.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 5, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

At Fairchild Semiconductor, his seminal Silicon Valley startup, Moore — a young chemist turned electronics entrepreneur — had the defining insight: silicon transistors, and microchips made of them, could make electronics profoundly cheap and immensely powerful. Microchips could double in power, then redouble again in clockwork fashion. History has borne out this insight, which we now call “Moore’s Law”, and Moore himself, having recognized it, worked endlessly to realize his vision. With Moore’s technological leadership at Fairchild and then at his second start-up, the Intel Corporation, the law has held for fifty years. The result is profound: from the days of enormous, clunky computers of limited capability to our new era, in which computers are placed everywhere from inside of our bodies to the surface of Mars.

Moore led nothing short of a revolution. In Moore’s Law, Arnold Thackray, David C. Brock, and Rachel Jones give the authoritative account of Gordon Moore’s life and his role in the development both of Silicon Valley and the transformative technologies developed there. Told by a team of writers with unparalleled access to Moore, his family, and his contemporaries, this is the human story of man and a career that have had almost superhuman effects. The history of twentieth-century technology is littered with overblown “revolutions.” Moore’s Law is essential reading for anyone seeking to learn what a real revolution looks like.