By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

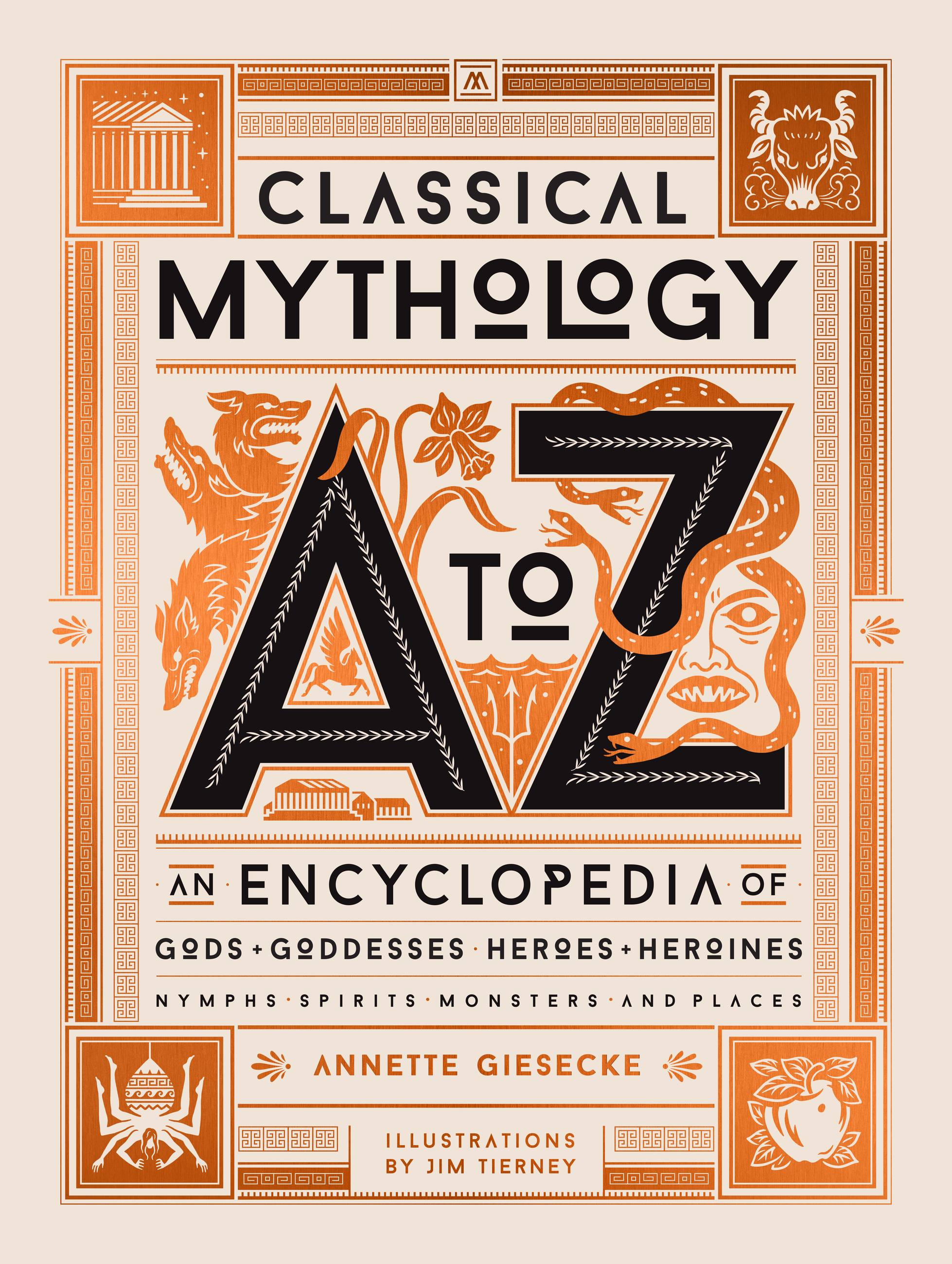

Classical Mythology A to Z

An Encyclopedia of Gods & Goddesses, Heroes & Heroines, Nymphs, Spirits, Monsters, and Places

Contributors

Illustrated by Jim Tierney

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 6, 2020

- Page Count

- 376 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780762497133

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $40.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 6, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Classical Mythology A-to-Z is a comprehensive and engrossing guide to Greek and Roman mythology. Written by Annette Giesecke, PhD, Professor of Classics and Chair of Ancient Greek and Roman Studies at the University of Delaware, this brilliant reference offers clear explanations of every character and locale, and captures the essence of these timeless tales.

From the gods and goddesses of Mount Olympus and the heroes of the Trojan War to the nymphs, monsters, and other mythical creatures that populate these ancient stories, Giesecke recounts, with clarity and energy, the details of more than 700 characters and places. Each definition includes cross-references to related characters, locations, and myths, as well their equivalent in Roman mythology and cult.

In addition to being an important standalone work, Classical Mythology A-to-Z is also written, designed, and illustrated to serve as an essential companion to the bestselling illustrated 75th-anniversary edition of Mythology by Edith Hamilton, including 10 full-color plates and 2-color illustrations throughout by artist Jim Tierney.

Genre:

-

"Annette Giesecke has recently added a wonderful and indispensable book to the corpus of mythology.... Each generation needs a mythology reference book like this, since mythology is immortal and always relevant to successive cultures but nonetheless helpful when language is both contemporary and universal as here."Patrick Hunt, Electrum Magazine

-

"Inviting and highly readable…a beautiful book: the layout is pleasing, with pages bordered in a sepia-toned Greek key design and frequent woodblock-style illustrations. Occasional full-page color plates in the same woodblock style add to the appeal. Charts showing, for example, the genealogy of the ruling house of Troy, are double-page spreads, clearly laid out and beautifully ornamented. Finishing with an appendix of gods, a glossary of ancient sources, and a detailed index, this is an ideal work for collections in need of a solid (and attractive) introduction to classical mythology."Ann Welton, Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use