Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

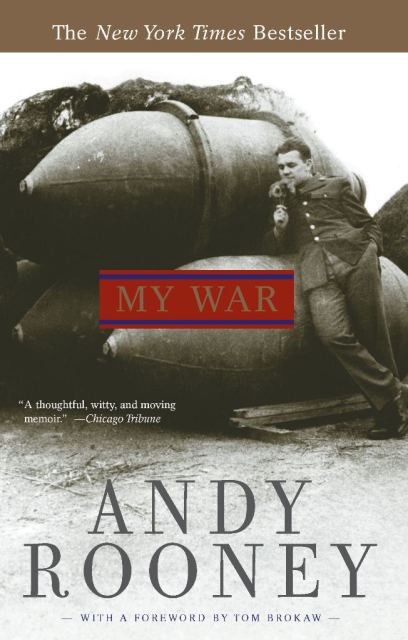

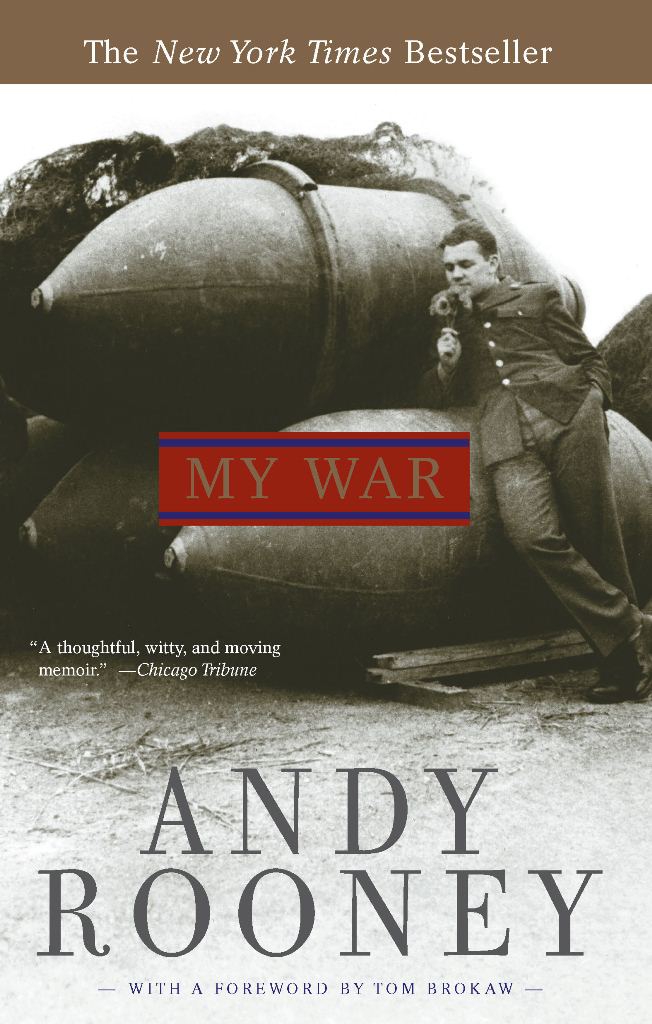

My War

Contributors

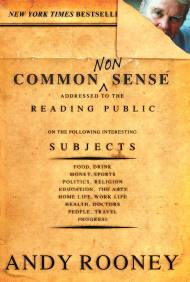

By Andy Rooney

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 18, 2008

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586486822

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 18, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

My War is a blunt, funny, idiosyncratic account of Andy Rooney’s World War II. As a young, naïve correspondent for The Stars and Stripes, Rooney flew bomber missions, arrived in France during the D-Day invasion, crossed the Rhine with the Allied forces, traveled to Paris for the Liberation, and was one of the first reporters into Buchenwald. Like so many of his generation, Rooney’s life was changed forever by the war. He saw life at the extremes of human experience, and wrote about what he observed, making it real to millions of men and women. My War is the story of an inexperienced kid learning the craft of journalism. It is by turns moving, suspenseful, and reflective. And Rooney’s unmistakable voice shines through on every page.