By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

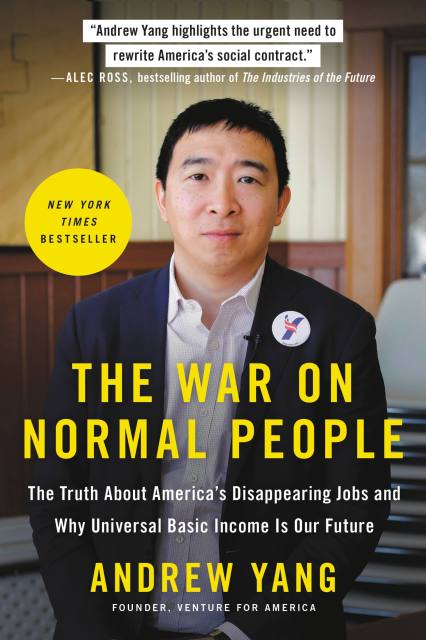

The War on Normal People

The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

Contributors

By Andrew Yang

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316414210

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The New York Times bestseller from CNN Political Commentator and 2020 former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, this thought-provoking and prescient call-to-action outlines the urgent steps America must take, including Universal Basic Income (UBI), to stabilize our economy amid rapid technological change and automation.

In The War on Normal People, Andrew Yang paints a dire portrait of the American economy. Rapidly advancing technologies like artificial intelligence, robotics and automation software are making millions of Americans’ livelihoods irrelevant. The consequences of these trends are already being felt across our communities in the form of political unrest, drug use, and other social ills. The future looks dire-but is it unavoidable?

In The War on Normal People, Yang imagines a different future–one in which having a job is distinct from the capacity to prosper and seek fulfillment. At this vision’s core is Universal Basic Income, the concept of providing all citizens with a guaranteed income-and one that is rapidly gaining popularity among forward-thinking politicians and economists. Yang proposes that UBI is an essential step toward a new, more durable kind of economy, one he calls “human capitalism.”

-

"Andrew Yang is one of those rare visionaries who puts dreams into action. The War on Normal People is both a clear-eyed look at the depths of our social and economic problems and an innovative roadmap toward a better future."Arianna Huffington,Founder and CEO of Thrive Global

-

"This book is a must read. Andrew Yang is tackling one of the biggest challenges facing our country the way only an entrepreneur can, but unlike most, he sees the big picture. Making money is good for you-but building a strong society and strong people is good for all of us. The topics Andrew addresses in this book aren't about some dystopian future way down the road. These things are happening today, and every entrepreneur should read this book to understand the challenges of the next decade."Daymond John, starof ABC's Shark Tank, bestselling author of The Power of Broke, andfounder of FUBU

-

"In this powerful book, Andrew Yang highlights the urgent need to rewrite America's social contract. In a call to arms that comes from both head and heart, Yang has made an important contribution to the debate about where America is headed and what we need to do about it."Alec Ross, New York Times bestsellingauthor of The Industries of the Future

-

"America desperately needs a wake-up call. This book will open your eyes to the ongoing effects of automation. Fortunately, aside from knowing full well the many challenges we face, Andrew Yang has a firm grasp of the solutions, most especially our need for Universal Basic Income. Read this book and hear the urgent call for abundance over scarcity, and humanity over abject madness. The clock is ticking."Scott Santens,Director, U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network

-

"Andrew Yang writes with passion and conviction, offering astute analysis--as well as a hopeful solution--for the looming challenge that may well define the coming decades: How can we ensure broad-based prosperity in a future where labor-displacing technology becomes vastly more powerful?"Martin Ford, NewYork Times bestselling author of Rise of the Robots

-

"A sobering portrait of a crumbling polity . . . [and] a provocative work of social criticism."Kirkus Reviews

-

"I found [The War on Normal People] fascinating and troubling."Major Garrett, host of CBS News' "The Takeout"

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use