Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

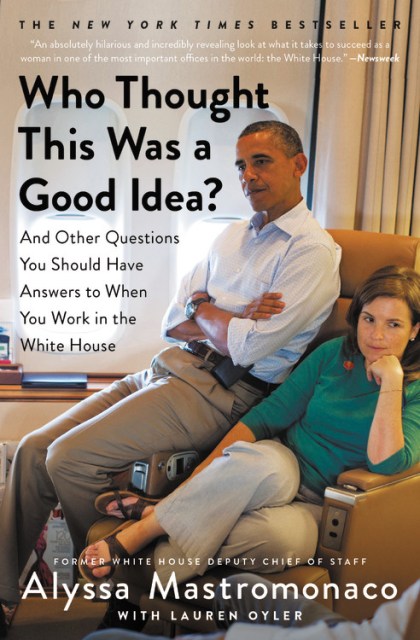

Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?

And Other Questions You Should Have Answers to When You Work in the White House

Contributors

With Lauren Oyler

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455588237

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

If your funny older sister were the former deputy chief of staff to President Barack Obama, her behind-the-scenes political memoir would look something like this . . .

Alyssa Mastromonaco worked for Barack Obama for almost a decade, and long before his run for president. From the then-senator’s early days in Congress to his years in the Oval Office, she made Hope and Change happen through blood, sweat, tears, and lots of briefing binders.

But for every historic occasion — meeting the queen at Buckingham Palace, bursting in on secret climate talks, or nailing a campaign speech in a hailstorm — there were dozens of less-than-perfect moments when it was up to Alyssa to save the day. Like the time she learned the hard way that there aren’t nearly enough bathrooms at the Vatican.

Full of hilarious, never-before-told stories, Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? is an intimate portrait of a president, a book about how to get stuff done, and the story of how one woman challenged, again and again, what a “White House official” is supposed to look like. Here Alyssa shares the strategies that made her successful in politics and beyond, including the importance of confidence, the value of not being a jerk, and why ultimately everything comes down to hard work (and always carrying a spare tampon).

Told in a smart, original voice and topped off with a couple of really good cat stories, Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? is a promising debut from a savvy political star.

-

"Always fascinating and very funny, Alyssa's book is full of juicy stories from one of the world's most glamorous jobs."Mindy Kaling, New York Times bestselling author of Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns) and Why Not Me?

-

"WHO THOUGHT THIS WAS A GOOD IDEA? is everything we've come to know and love about Alyssa over the decade we worked with her: brilliant, funny, grounded, and inspiring. Anyone who's interested in politics - especially young people - should read this book."Dan Pfeiffer and Jon Favreau, former communications director and speechwriter for President Barack Obama

-

"Few people have had as much access and influence over national events over the last decade as Alyssa Mastromonaco. No matter how serious the crisis or hard the problem, Alyssa took care of it with great skill and professionalism, and even greater humor. This book tells the story of a young woman succeeding under extraordinary circumstances, and throughout it all, never taking herself too seriously."Stephanie Cutter, former deputy campaign manager for President Barack Obama

-

"I've often wondered how a woman can be so many things wrapped up in one dynamic package. Alyssa is my fairy godmother: she's wise, resourceful, insanely smart, and makes me laugh in a very special way. Her stories - from the front line of the White House to her kitchen - will entertain, inspire, and humor you for a long time to come."Amanda de Cadenet

-

"Alyssa is a force: whip-smart, humble, and funny as hell. Her writing is as fearless as she is."Sophia Amoruso, founder and CEO of Girlboss

-

"A candid and charming memoir of her unexpected career in government...The memoir abounds with intimate glimpses of Washington, D.C., celebrities (Biden, Clinton, Michelle Obama, and scores more) and cheerfully dispensed survival strategies. An entertaining look inside the White House."Kirkus

-

"When imagining working in the White House, many picture meaningful meetings, glamorous dinners, and high-stakes decision making. It can be all of those things. But as Alyssa Mastromonaco writes in WHO THOUGHT THIS WAS A GOOD IDEA?, the reader gets a real and raw peek behind the curtains where Alyssa experiences the good, the bad, the distressing, and the often hilarious. Alyssa has real grit and grace, and her book is her story very well told."Dana Perino, New York Times bestselling author of And the Good News Is... and Let Me Tell You About Jasper...

-

"A combination memoir and compendium of very good suggestions about how to get ahead -- very far ahead -- at an early age."The Washington Post

-

"[WHO THOUGHT THIS WAS A GOOD IDEA] is brimming with...humorous, behind-the-scenes anecdotes, as well as up-close-and-personal moments with Obama that shed new light on who he is as a leader, man and friend."People.com

-

"A moving, funny, and sometimes heart-wrenching look back at the years [Alyssa Mastromonaco] spent in politics and by [President Obama's] side."PopSugar.com

-

"This relatable memoir is packed with juicy on-the-road stories and crisis management advice, and presents a strong case for embracing a sense of humor in the face of humbling setbacks."Esquire.com

-

"Mastromonaco's memoir successfully avers that a tough, high-profile job is attainable and enjoyable for any woman who is as smart, ambitious, humble, silly, and hard-working as she is. Her book is full of enjoyable storytelling intended as encouragement for women of her generation and younger."Publishers Weekly

-

"A must-read for anybody who's even remotely interested in how Washington works, but is worth reading for anyone who enjoys brilliant wit and once-in-a-lifetime stories...you'll probably end up reading it more than once."Popsugar.com