Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

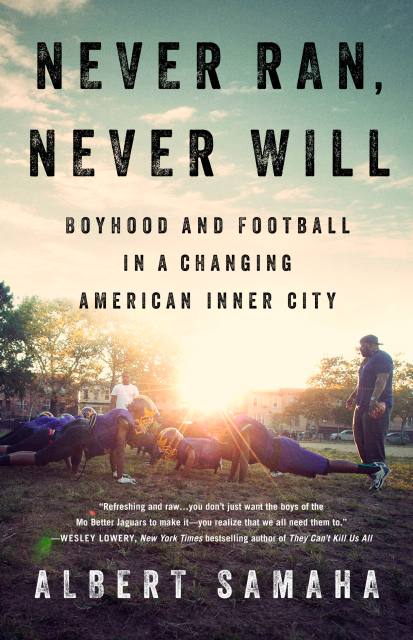

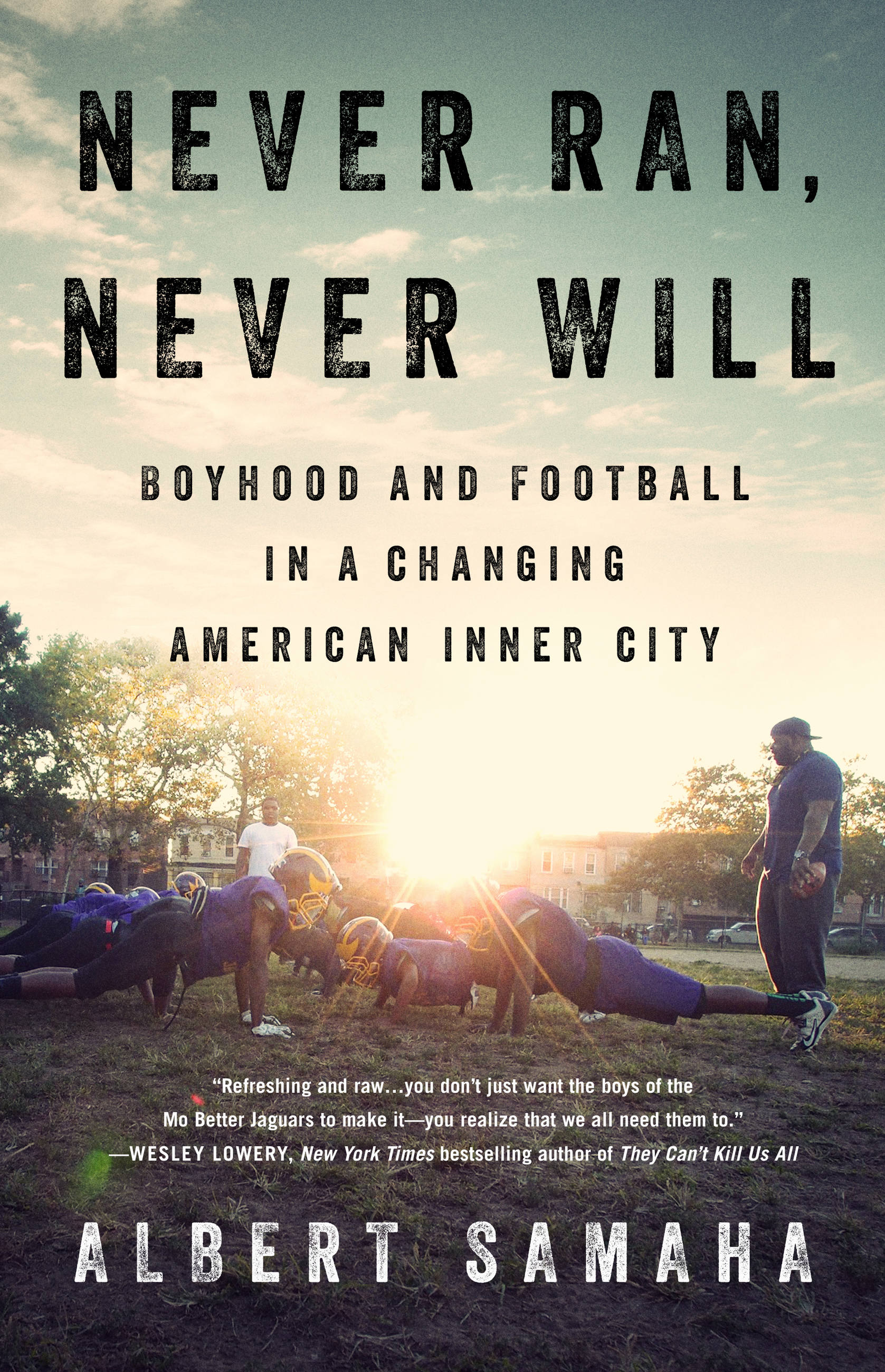

Never Ran, Never Will

Boyhood and Football in a Changing American Inner City

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 4, 2018

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541767867

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 4, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This uplifting story of a boys’ football team shines light on the under-appreciated virtues that can bloom in impoverished neighborhoods, even as nearby communities exclude them from economic progress.

Never Ran, Never Will tells the story of the working-class, mostly black neighborhood of Brownsville, Brooklyn; its proud youth football team, the Mo Better Jaguars; and the young boys who are often at the center of both. Oomz, Gio, Hart, and their charismatic, vulnerable friends, come together on a dusty football field. All around them their community is threatened by violence, poverty, and the specter of losing their homes to gentrification. Their passionate, unpaid coaches teach hard lessons about surviving American life with little help from the outside world, cultivating in their players the perseverance and courage to make it.

Football isn’t everybody’s ideal way to find the American dream, but for some kids it’s the surest road there is. The Mo Better Jaguars team offers a refuge from the gang feuding that consumes much of the streets and a ticket to a better future in a country where football talent remains an exceptionally valuable commodity. If the team can make the regional championships, prestigious high schools and colleges might open their doors to the players.

Never Ran, Never Will is a complex, humane story that reveals the changing world of an American inner city and a group of unforgettable boys in the middle of it all.

-

"Samaha brings empathy and scrutiny to his reporting... There is much to enjoy and at the best moments to admire in this book... Never Ran, Never Will proves the continued salience of urban sports as a subject for exploring larger issues of race and class."New YorkTimes Book Review

-

"Refreshing and raw, Never Ran, Never Will tracks the boys of Brownsville, Brooklyn as they age out of innocence and details the efforts of the devoted men and women laboring to guide them into adulthood. By the last page of Albert Samaha's compelling debut, you don't just want the boys of the Mo Better Jaguars to make it - you realize that we all need them to."Wesley Lowery, Pulitzer Prize winning Washington Post national correspondent and author of the New York Times bestselling They Can't Kill Us All

-

"Never Ran, Never Will is the irresistible story of the Mo Better Jaguars, a football team of hard-luck boys in low-income Brownsville, Brooklyn. With dazzling prose, Albert Samaha's big beautiful book about teamwork and ambition, growing up and breaking away, will touch you with its heart and grace."Don Van Natta, Jr., ESPN senior writer, New York Times bestselling author, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize

-

"Good narrative nonfiction requires a kind of alchemy-thorough reporting and incisive writing are essential, but the most important ingredient is time. Albert Samaha's years-long commitment to this tale of striving Brooklyn kids and their dedicated football coaches shines through on every page. The result is a rare gift: a story with genuine characters, real texture, and deep, sensitive insight."Nate Blakeslee, author of American Wolf and Tulia

-

"Samaha takes readers by the hand and leads them on a visceral tour of a peril-filled world that, nevertheless, thanks to people like Legree, can also become a seeding ground for hope. An important book on many levels."Booklist, Starred Review

-

"An inspiring tale... At the heart of Samaha's unflinching book are the life-affirming themes of sports, transcendence, courage, and manhood."Publishers Weekly

-

"Albert Samaha writes with grit, grace and compassion about coming of age in a hard place. The young men of the Mo Better Jaguars-and their tireless coaches-face long odds on the field and in the streets. It's impossible not to root for them, to marvel at their determination and heart, and to share in their dream of a better future."Jessica Bruder, author of Nomadland: Surviving America inthe Twenty-First Century