Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

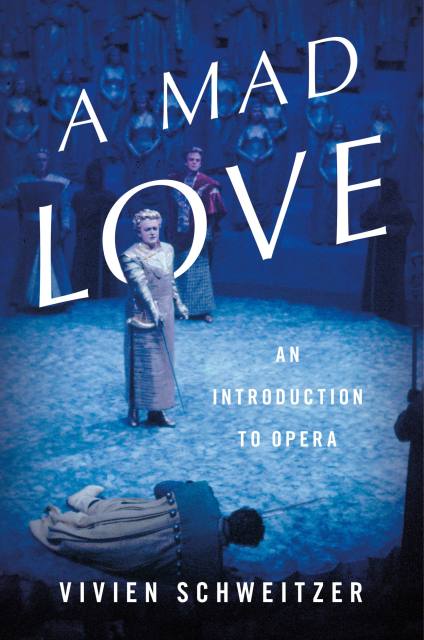

A Mad Love

An Introduction to Opera

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 18, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096947

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 18, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

There are few art forms as visceral and emotional as opera — and few that are as daunting for newcomers. A Mad Love offers a spirited and indispensable tour of opera’s eclectic past and present, beginning with Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo in 1607, generally considered the first successful opera, through classics like Carmen and La Boheme, and spanning to Brokeback Mountain and The Death of Klinghoffer in recent years. Musician and critic Vivien Schweitzer acquaints readers with the genre’s most important composers and some of its most influential performers, recounts its long-standing debates, and explains its essential terminology.

Today, opera is everywhere, from the historic houses of major opera companies to movie theaters and public parks to offbeat performance spaces and our earbuds. A Mad Love is an essential book for anyone who wants to appreciate this living, evolving art form in all its richness.